Neighbourhood watch

Sheltered, sunlit location. Above flood level, and with excellent drainage. Little traffic and minimal industry.

No wonder this patch of forest real estate is in such demand!

At first glance it may not look much, but for sand-nesting insects this particular forest path and surrounds is the place to be.

For the past couple of weeks, all foot traffic has been diverted and the area monitored. A locked suburb, with me leading the neighbourhood watch committee (of one). I record who comes and goes, what they build, how they behave, who they visit.

Obsessive? … no doubt.

Intrusive? … yeah, just a bit.

Interesting? … absolutely!

The November 2022 roll call and street map

The diversity of insects currently nesting in this one small patch astounds me. It must be getting extremely crowded below ground – burrows and side-tunnels, nest chambers stocked with food, and larvae of all kinds.

The diversity of insects currently nesting (or guesting) in this one small, sunny patch of the forest floor.

The neighbourhood map, showing where each species is concentrated. There is more overlap, or course, and I certainly haven’t mapped every nest. Plus Sphodrotes has only just started, so I’ve yet to see where they will settle in the largest numbers.

Remarkably, many of the nesting adults I’m seeing now would have spent their own larval lives here in this same patch, hatching last summer or autumn and then overwintering underground as pupae or resting adults.

All winter long we tread this path, not giving a thought to the diversity directly beneath our feet. But come November the neighbourhood partying swings into gear, above ground. The bustle and diversity is impossible to ignore. For me, anyway.

This is just the latest episode in my ongoing quest to learn more about our local crabronid wasps. I’ve been sitting in the sand, watching wasps come and go, for several summers now. Yes, it’s an obsession. But a useful one, I would argue. There are remarkably few studies of the behaviour of sand-nesting wasps in Australia. Since the ground-breaking (ha, pun!) works of Evans and Matthews 40 to 50 years ago (see the reference list), little new information has come to light. So who knows? My observations may prove valuable to someone, some day.

And in the meantime, I’m having a ball! Watching, photographing, reading, and watching some more. Neighbourhood life is so much richer, interwoven and complex that I had ever imagined.

If I had to list three highlights, it would be these:

Finding two species of nesting wasp in a genus I’ve never seen before … and learning more about their nesting habits. In particular, I watched as the female Sericophorus collapsed the entrance to her underground nest. After studying a huge nesting colony in Canberra in 1969-70, and providing the first biological information about Sericophorus in Australia, Matthews and Evans noted that “no final nest closing behavior was observed” (Matthews & Evans 1971, p.422) They speculated on what may have led to the eroded entrance … but I watched it happen. Twice! Two nests, two females, both nesting within a few cm of each other on the sandy path.

Witnessing the mating of tiny velvet ants. This is very rarely observed – and perhaps never before photographed for Australian mutillids of the subfamily Sphaeropthalminae (see iNaturalist record). Even sightings of males are relatively rare … and I have been seeing them every day, hovering alongside the path.

Home invaders, caught in the act. Small flies loiter around the path, clearly up to no good. Miltogramminae and Apotropina are both recognised nest intruders … and I caught them in the act – a satellite fly (Protomiltogramma, probably) dropping a larva down an open Cerceris nest, and sneaky little Apotropina moving in and out of Sericophorus nests, at will.

Now for the full story …

First the home makers, then the unwelcome guests, and finally the drifters, squatters and general miscreants. Every neighbourhood has them!

The home makers

Podagritus (Crabroninae: Crabronini)

As predicted, Podagritus was among the first to appear. These gangly, colourful wasps are nesting exactly where I saw them last year … presumably the new generation returning to the sands of their birth. Their little enclave is not far from the path, amongst scattered sedge, grasses and forbs. It is now a month since they started nesting and the breeding site is as busy as ever, with additional aggregations nearby. They must be having quite an impact on the local fly population!

Cerceris (Philanthinae)

Cerceris are also back in large numbers, again nesting in the places I’d expect. Have their numbers grown, or am I just getting better at spotting them? The population density certainly seems higher than ever.

Bembix (Bembicinae: Bembicini)

One of the more recent arrivals, but a species that’s hard to miss. They’re large, showy and noisy. The blue-white stripes and yellow face are unmistakable, yet identification beyond genus is exceedingly tricky. There are currently 84 species listed for Australia (AFD), and we may well have more than one species here. Thanks to the generosity of Robert Matthews, I may soon be able work out who’s who, but that’s for a later study (and another blog).

Many, if not most, solitary aculeate wasps practice what is termed ‘mass provisioning’. That is, they stock a nest chamber with food, lay an egg, seal the door … and that’s it. The mother either goes on to build and stock another chamber, or she departs, usually kicking the door closed behind her as she goes. The paralysed prey stays fresh (i.e. alive) as the growing larva consumes one after another.

Apparently that is not the Bembix way. Her long burrow usually terminates in a single chamber, and she attends the larva as it grows (Bohart & Menke 1976). She delivers a fresh fly, lightly paralysed, as needed.

Bembix typically hunt flies of all kinds, from flower-feeding hoverflies to predatory robber flies. Occasionally they even take non-dipteran prey, including damselflies, bees and various wasps (Evans & O’Neill 2007). I’ve only ever seen our local species carrying flies, but perhaps I need to watch them a little more closely. Perhaps later … for right now their near-neighbours are distracting me.

Austrogorytes (Bembicinae: Bembicini)

Smaller than its local Bembix cousins, this rather large sand wasp is a species I first noticed in 2020. That summer I was only able to find a single nest. Now we have many! I’m no doubt better at spotting them now that I know what to look for. But again, I suspect the local population is growing. They’re still a minority group in the neighbourhood, currently far outnumbered by Cerceris and Podagritus.

If the bugs are small, a nesting Austrogorytes may need more than 20 to fully stock a single cell – and unlike Bembix, she builds a multi-chambered home. No doubt she learns where to find them and makes repeated trips to the same hunting ground. She fills each cell with paralysed bugs before laying a single egg on top of the last one and then closing the cell (Evans & Matthews 1971b). The classic mass-provisioning approach.

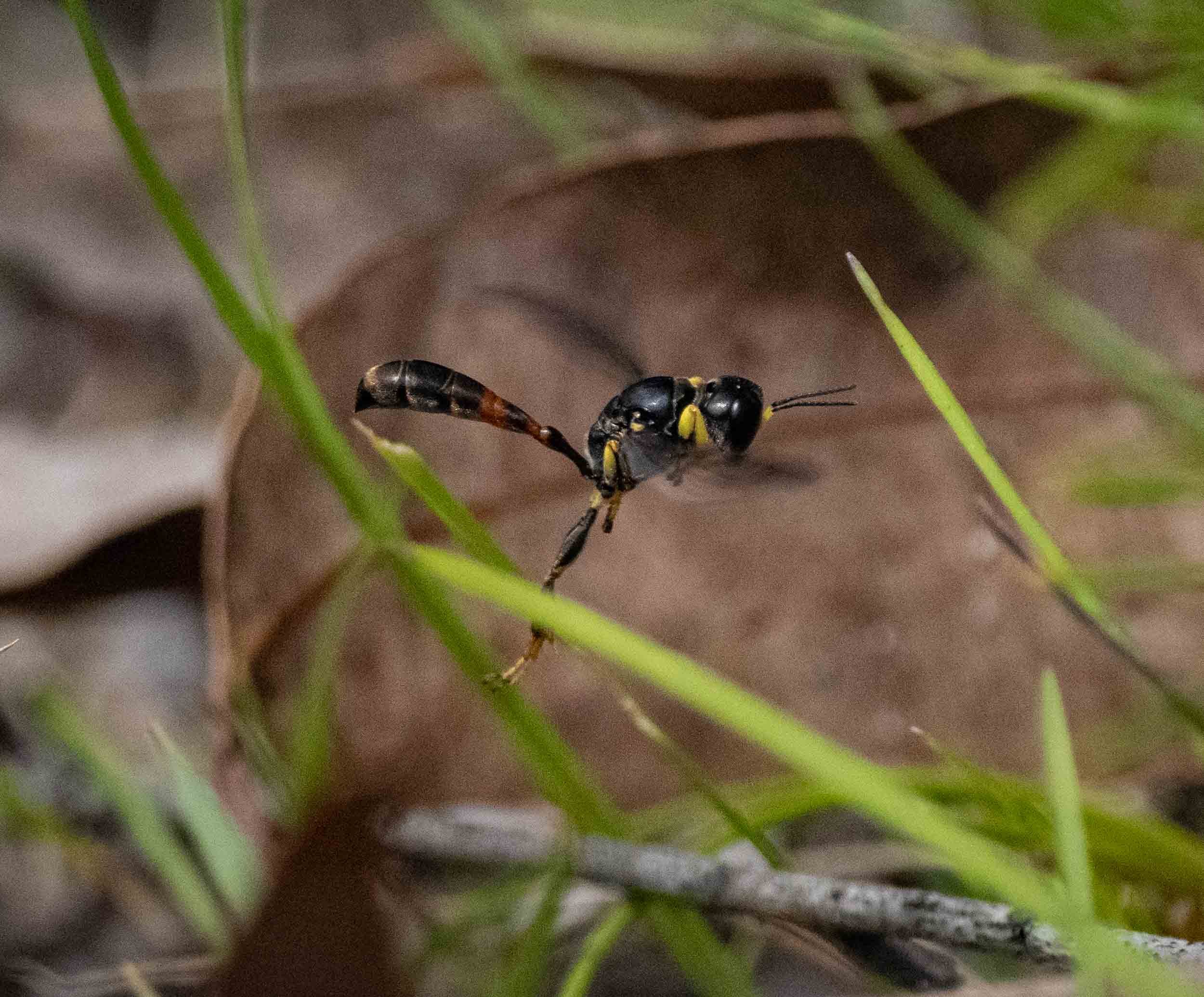

Sphodrotes (Crabroninae: Miscophini)

I’ve been on the lookout for this one. They’re small, but I know them well from past years (see ‘More wasp diggings’, January 2021). They have distinctive behaviour and are good photography subjects – they often perch on plants, unlike many of the other wasps. Until recently, I had just one sighting, but I was on the lookout for more.

And on 28th November, ‘bingo’! … male Sphodrotes swarming amongst the low-growing plants immediately alongside the Podagritus patch! When not engaged in looping flight about 30cm above ground, they land and fossick briefly among the leaf litter or perch on low plants, turning this way and that, antennae waving. They’re clearly seeking females.

No females in evidence yet, but I predict they’ll make an appearance any day now.

Sphodrotes build deep nest burrows, with a sizeable mound and a wide open door. But they’re not easy to find. Invariably, they are hidden under leaves or debris on the forest floor.

Sphodrotes hunts shield bugs, usually nymphs but occasionally adults too. That is known from studies of a Queensland species (Evans 1973) and matches my own observations here in past years. Of course, I’ll be watching closely to see if the pattern this year is the same. Little has been published about the biology of this group, so it’s easy to justify spending more time wasp-watching this summer.

Sericophorus (Crabroninae: Miscophini) – large and small

Species 1 - possibly Sericophorus viridis

A showy new arrival appeared mid month and settled alongside the mainstreet, in the compacted bare sand of the track. I’d never seen one before, but the identity check was quick. That stout shape, metallic body and red legs … Sericophorus. They are reported to hunt blow flies, and look a little bit like them. They even fly like flies.

The wasp built a rough mound that seemed to grow overnight, and soon a second Sericophorus built alongside. They soon moved on, their hastily-built mounds already crumbling away. But in recent days a couple more holes have appeared nearby … I need to investigate these soon.

This species (probably S. viridis) is the size of a small blowfly, and the metallic blue-green-gold colours are also fly-like. A study of a large nesting aggregation in Canberra found that S. viridis hunted only in the early morning … and only captured male blowflies (Matthews & Evans 1971). The authors speculated that the wasps may be targeting male flies (Calliphora tibialis, in this case) engaged in early morning territorial challenge behaviour. Perhaps the flies mistake the similar-looking incoming wasps for rival males, challenge them … and lose. Seems feasible.

I have yet to see a large Sericophorus returning with prey, so I can only assume that they’re hunting our local blowflies.

Species 2 - a second, tiny Sericophorus

A few weeks ago I spotted the tiniest of wasps, struggling with a fly as it clambered about the leaf litter. This was along a different forest path, a nearby neighbourhood. The behaviour was that of a sand-nesting wasp, but so tiny!

Despite regularly searching the area, I didn’t see another such wasp … until this week.

While scanning the main sandy path of ‘the neighbourhood’ I spotted this tiny wasp. Clearly the same as the fly-carrying female I’d seen earlier. Having worked my way through the various possibilities, I’m confident that this is a Sericophorus – but not the same species as Wasps A and B. This one is tiny. And a daytime hunter.

Getting to species level identification is not possible for the smaller of the Sericophorous – there are 95 species listed on AFD, and I have only a handful of photos. However, having never noticed this genus before, I’m rather excited to add not one but two Sericophorus to our forest home list, even if for now they have numbers rather than species names.

Lipotriches australica (Halictidae: Nomiinae)

Many of Australia’s native bees nest in soil, so it should be no surprise that the neighbourhood has its share of vegans.

By far the most obvious bees in the neighbourhood are the Green-and-gold Nomia Bees, Lipotriches australica. Their nests are numerous, each with a neat central opening leading into a vertical tunnel. The mounds vary in size and are often quite low. They favour the edge of the path … a nice, leafy suburb.

Unlike the crabronids, I frequently see the bees at work away from the nest area. Lately they have been one of the most common visitors to flowering Dianella and Stylidium, and Paul has been photographing them on the Kunzea too … which just happens to be flowering profusely right alongside the path (see Busy and busier). Lipotriches are generalists, opportunistic in their foraging habits.

More bees – Euhesma (Colletidae: Euryglossinae) and Homalictus (Halictidae: Halictinae)

When I spotted these two bee species, they were still house-hunting. Apparently no established burrows yet, but they seem ready and keen to move in.

Unwelcome guests

Despite the high density housing of the neighbourhood, the residents get along remarkably well. But then there are the unwelcome visitors! They move in uninvited, take over the living space, and eat the hosts out of house and home.

Velvet ants (Mutillidae)

Over the past couple of weeks I’ve become quite good at spotting these small wasps. And there are far more out there than I had ever imagined! The tiny, wingless females scurry about the bare path and the ground between nearby plants. Their antennae are constantly on the move, tapping the sand. Periodically they explore the nest mounds and burrows of the bees and ants … and occasionally slip inside, briefly.

The velvet ants seem as interested in abandoned nests as they are in active ones. And here’s why.

Fully-fed, resting offspring in sealed rooms are the target for these fuzzy little intruders. Ground-nesting bees and wasps are high on the list, although velvet ants aren’t particularly fussy eaters (Brothers 1989; Luz et al. 2016). Female mutillids are long-lived and patient … they monitor nests and wait until the host’s larvae have consumed all their provisions and started to pupate. The mutillid then penetrates the chamber, lays an egg on the helpless insect, and departs. Her egg soon hatches, and the intruder devours the bee or wasp larva. Once fully grown it pupates and develops into an adult mutillid - taking full advantage of the stolen accommodation.

Unwelcome visitors indeed!

Note: Last year I discovered mutillids inside the nest of a mud-nesting crabronid wasp (Pison, Crabroninae, Trypoxylini). For the full story, see ‘A window into mud-nests’.

Satellite flies (Sarcophagidae: Miltogramminae)

Hanging about the neighbourhood, and clearly up to no good, are golden-faced satellite flies. They fly circles around incoming bees and wasps (hence their common name), tracking the prey-laden females to their nests. They also strut about the rim of the nest mounds, or confidently perch on nearby rocks or leaves. And when they get the chance, they move in. Well, their offspring do.

Miltogramminae drop live young into the nest burrow or onto the incoming prey. Unlike the velvet ants, these little intruders are after the food stash, rather than the host larva. They are food parasites, or ‘kleptoparasites’. Paralysed flies, bugs and beetles are all fair game, as are the pollen stores of nesting bees.

And they have quite an impact on the unfortunate home makers. Miltogramminae are a major cause of mortality among many (or perhaps most) fossorial wasps (Marshall 2012). The host larvae starve, or are eaten along with the rest of the cell contents.

It’s likely that many of the nests are already home to satellite fly larve. They seem particularly keen on Cerceris nests … and I actually spotted a fly hunched over a Cerceris nest burrow, her larva about to drop. High drama on high street!

Sneaky flies (Chloropidae: Apotropina)

Active wasp nests seem to attract Apotropina. A female wasp returning with prey is quickly greeted at the nest mount by the ever alert little flies, and building activity inevitably attracts their attention. These sneaky flies stand vigil on the mound, darting down into the opening when given the chance. They have been particularly obsessed with the nest-collapsing activities of Sericophorus (as have I).

Apparently Apotropina larvae are scavengers, feeding on nest debris (Evans & O’Neill 2007) rather than stealing food outright or killing the host’s larvae. Nevertheless, they take advantage of the nest as a source of food and a safe place to grow and develop (Evans & Matthews 1971b). Even if they perform some housekeeping chores, they remain uninvited guests. The adult wasps don’t seem too thrilled to see them lurking about their doorways.

Bee flies (Bombyliidae: Meomyia)

All spring, Meomyia and related bee flies have been a common sight across the forest. They make their presence known, buzzing as they hover around flowers or sand patches. The females are particularly obvious as they delicately touch down, gathering sand to coat their eggs.

What I didn’t realise until doing a bit more reading was where they put those eggs. They flick them into the burrows of solitary, sand-nesting bees (Marshall 2012; Grove et al. 2021)! The larvae find their way into the host cells … and then they wait. Once the bee larva has finished feeding and reaches the prepupal stage, the Meomyia larva attaches to it and feeds. The baby bee is lost, the young bee fly gains food …and a home.

Drifters, squatters and those just passing through

Stiletto flies (Therevidae: Bonjeania)

Now, I may be jumping to conclusions here, but I have my suspicions about these little stiletto flies. They land on the path and seem to just sit. Perhaps they are innocent, perhaps not.

Very little is known about the biology of flies in this family, but their larvae live as predators in sandy soil and actively hunt invertebrates (Marshall 2012). Presumably a nest chamber stocked with paralysed prey, or a defenceless wasp larva, would be fair game.

Flower wasps (Thynninae)

There’s another type of wasp burrowing away in the neighbourhood. Flower wasps.

Unlike the crabronid wasps and the bees listed above, flower wasps do not build a stable burrow or nest mound. The flightless females simply disappear below ground and hunt beetle larvae which they then stash away, paralysed, as food for their own offspring. (Or so it is for some species. Details for most species remain unknown). Periodically, a female thynnine resurfaces and calls in a male.

The forest is home to many, many different species of flower wasp and they are widespread … including in my neighbourhood of study. As I sit watching the crabronid wasps and bees come and go, mating flower wasps are a common sight, including swarming males attracted to females emerging from the sand.

Spider wasps (Pompilidae)

Spider wasp activity has been building for weeks now. I see them searching the ground for spiders, hauling their paralysed prey, or feeding at flowers. But some of them also seem interested in the nest mounds.

Initially this puzzled me. Surely they’re not hunting wasps or seeking to steal their prey. No. They’re either checking the holes for live spiders, or they’re house hunting. Most pompilids nest in the soil and they often take advantage of the abandoned burrows of other species. Saves doing all the hard work themselves.

Other wandering opportunists

There is life in the neighbourhood this month beyond the stories I’ve covered above. Scavenging ants, hunting bugs, and spiders of all kinds. Who knows what effects these have on the resident wasps and bees? Some of the locals must fall prey to above ground predators, and the underground activities of small, foraging ants have the potential to devastate entire nesting aggregations (Martins et al. 1998). I’m hoping that at least some of the next generation of wasps and bees make it through to emerge next year.

Always one more surprise

Here’s one I’ve not seen before!

Determinedly digging into the coarse sand of the path. A bit like a velvet ant, but not hairy enough. Reminds me of our local thynnine flower wasps, yet not a good fit for them either.

I’ve sought suggestions from those in the know by posting this sighting on iNaturalist. There is some ongoing debate, but the wasp is likely to be a near relative of the thynnine flower wasps, a Thynnidae of the subfamily Anthoboscinae. One thing is sure, it’s a species – indeed a subfamily – that we’ve never recorded here in the forest before. They must be either scarce or secretive. Perhaps both. There are only a handful of Australian sightings of this taxon in the Atlas of Living Australia, so they’re clearly not common.

Yet another reward for spending so many hours staring at a small patch of sand.

References

Australian Faunal Directory (AFD) https://biodiversity.org.au/afd/home

Bogart, R.M. & Menke, A.S. 1976. Sphecid wasps of the World: A generic revision. University of California Press.

Brothers, D.J. 1989. Alternative life-history styles of mutillid wasps (Insecta, Hymenoptera). In: Bruton, M.N. (Ed.), Alternative Life-History Styles of Animals. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Netherlands, pp, 279-291

Evans, H.E. & Matthews, R.W. 1970. Notes on the nests and prey of Australian wasps of the genus Cerceris (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Journal of the Australian Entomological Society, 9: 153-156

Evans, H.E. & Matthews, R.W. 1971a. Notes on the prey and nests of some Australian Crabronini (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Journal of the Australian Entomological Society, 10: 1-4

Evans, H.E. & Matthews, R.W. 1971b. Nesting behaviour and larval stages of some Australian Nysssonine sand wasps (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Australian Journal of Zoology, 19: 293-310

Evans, H.E. 1973. Observations on the nests and prey of Sphodrotes nemoralis sp. n. (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Australian Entomological Society, 12: 311-314

Evans, H.E. & O.Neill, K.M. 2007. The Sand Wasps: natural history and behaviour. Harvard University Press.

Grove, S., Byrne, C., Bonham, K., Moore, K. & Cook, L. 2021. Invertebrate discoveries arising from a survey of Musselroe Wind Farm. The Tasmanian Naturalist, 143: 77-91

Luz, D.R., Waldren, G.C. & Melo, G.A.R. 2016. Bees as hosts of mutillid wasps in the Neotropical region (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Mutillidae). Revista Brasileira De Entomologia, 60: 302-307

Marshall, S.A. 2012. Flies: The Natural History and Diversity of Diptera. Firefly Books, Buffalo New York.

Martins, R.P., Soares, L.A. & Yanega, D. 1998. The nesting behavior and dynamics of Bicyrtes angulata (F. Smith) with a comparison to other species in the genus (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research, 7(2): 165-177

Matthews, R.W. & Evans, H.E. 1971. Biological notes on two species of Sericophorus from Australia (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 77: 413-429

Wcislo, W.T. & Engel, M.S. 1996. Social behavior and nest architecture of nomiine bees (Hymenoptera: Halictidae; Nomiinae). Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society, 69(4): 158-167