Firewood & mystery wasps

Most flying insects disappear from the forest during winter. Many adults perish after breeding in spring and summer, while others effectively hibernate until the longer days and warmer weather returns. From June to early August, I can prowl for hours with barely a glimpse of a wasp, bee or fly.

So during winter I shift my focus to indoor investigations. The crabronid project is ongoing, and this year I've started to tackle the Crabronini in earnest. How does one tell a Williamsita from an Ectemnius, for example? And what about Dasyproctus? There are numerous sightings on iNaturalist to work from, so can I add anything to their suggested identifications?

Lots of desk-based research: seeking out copies of manuscripts from the early and mid 1900's; translating the Latin and French (roughly, in most cases); downloading the few available images of type specimens; developing summaries and resources for future use. The equivalent of a huge jigsaw puzzle, with no edge pieces. My kind of fun.

But in mid June a major distraction arrived in the form of a tiny wasp. Inside the house, clinging to the glass of a north-facing window. Clearly crabronid-like, but unlike any wasp I have photographed before!

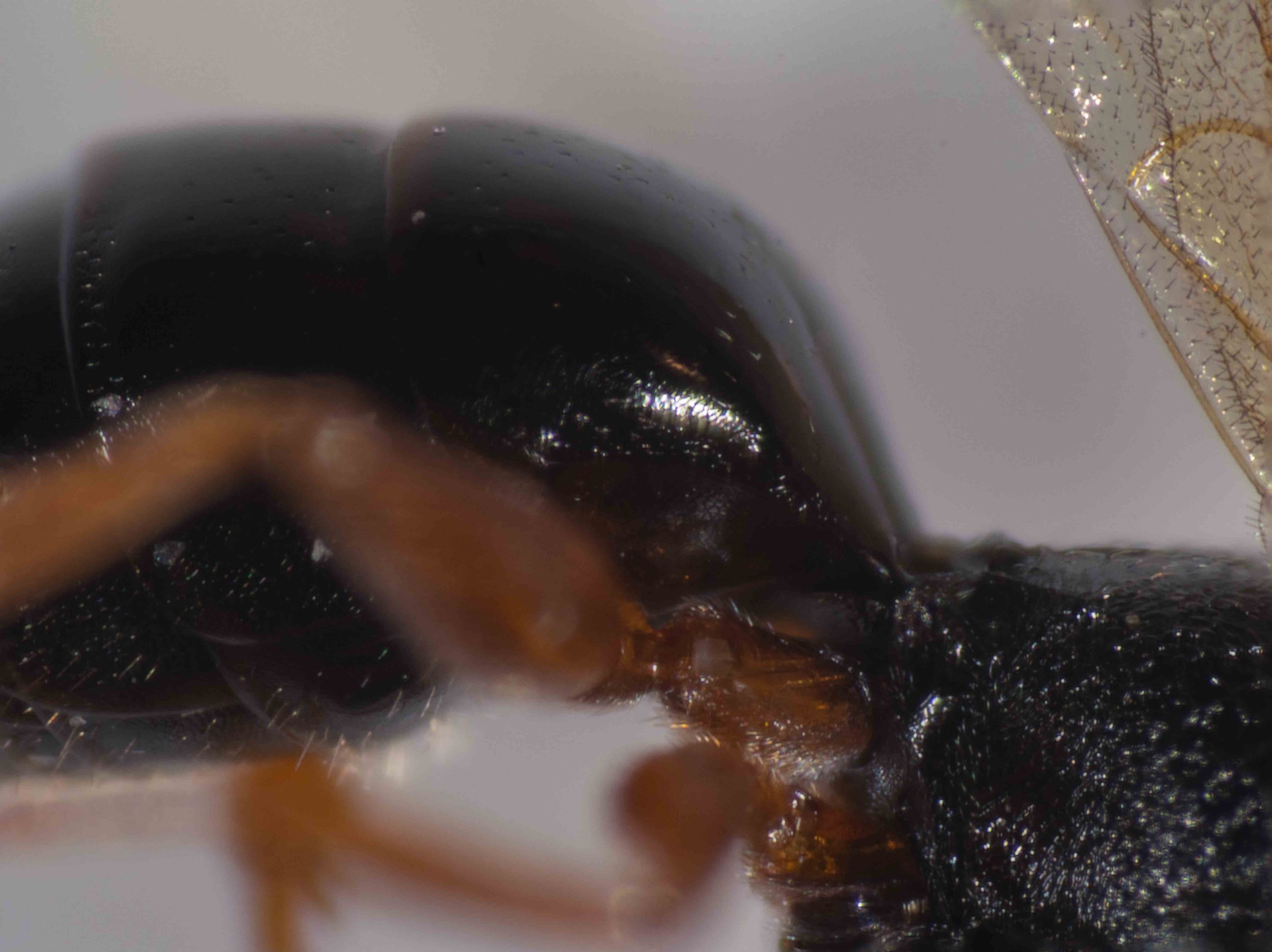

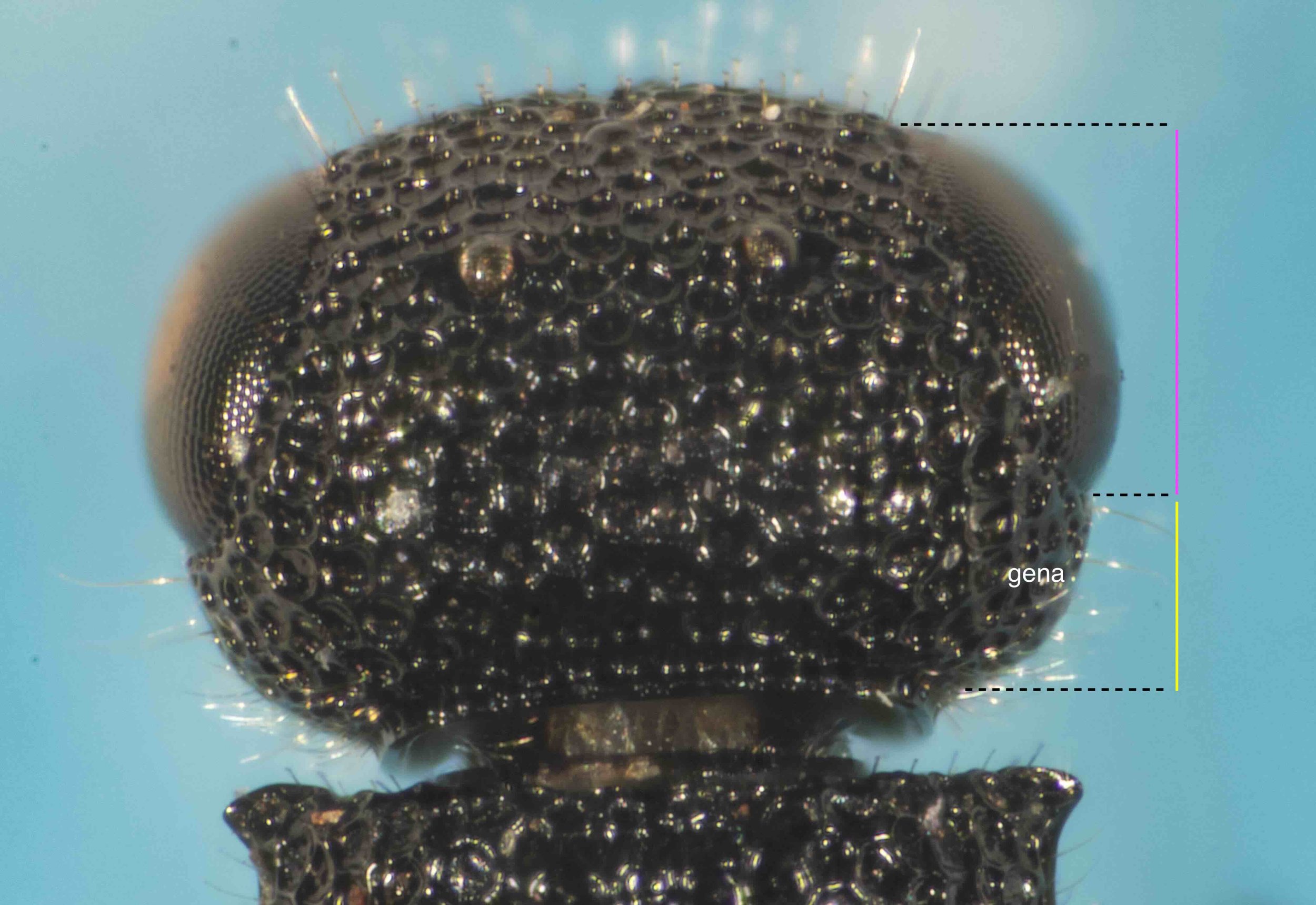

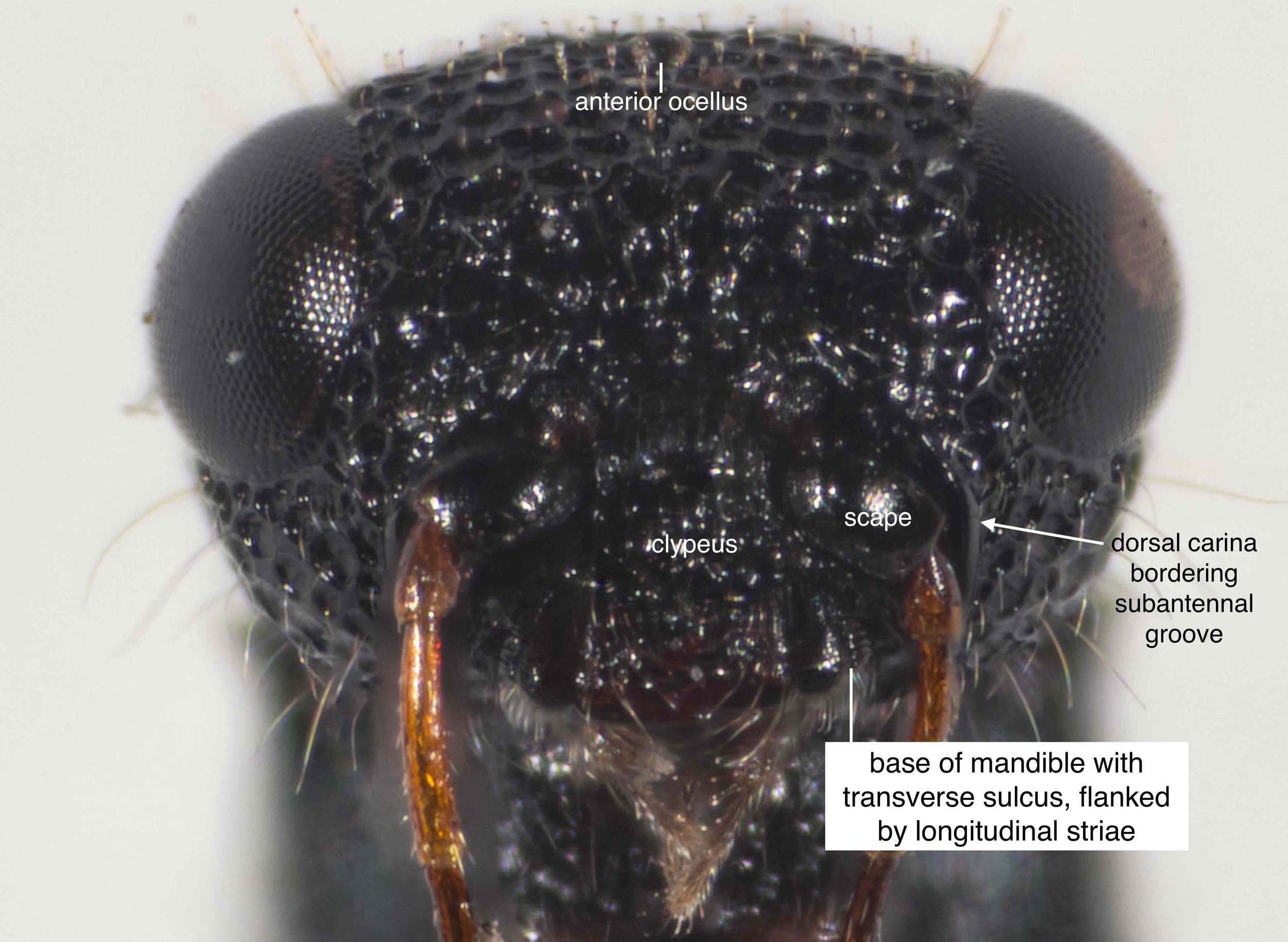

Window-wasp #1 ... the square-shaped head suggests crabronid, but she is quite unlike any crabronid I've studied before. At less than 5mm in length, I might easily have overlooked her out in the forest. (specimen ID 2406A)

Within days, I discovered two more wasps at the same window, but this time both lie dead on the sill. One looks identical to wasp #1 … the other presents a whole new mystery! Let’s call this second mystery ‘Window-wasp #2’.

Found dead on window sill ... and looks just like Window-wasp #1 found a few days earlier. (specimen ID 2406B)

Window-wasp #2 ... my first thought was "who on earth are you?". Those long antennae and mouthparts tucked away ventrally, the coarsely sculptured cuticle, the round head. Again, this is a very small insect, at just 3.9mm overall head-body length. (specimen ID 2406C)

Weeks pass as I work my way towards tentative identifications of Window-wasps #1 and #2 ... and then I decide to check the window sill again. Good thing I don't dust too often! Another extraordinary haul, including one that looks a bit like Window-wasp #2 … but different. So he became Window-wasp #3.

Window-wasp #3 ... like #2, but slightly different shape and proportions. And a little bit larger overall, at over 5mm head-body length. (specimen ID 2408B)

Damaged and dusty, but clearly a reed bee – Exoneura

Not only dusty, but this one was wrapped in a spider's web. I'll be able to clean her up for a closer look ... later. Even I can only tackle so many mysterious wasps in one sitting! (specimen ID 2408C)

Yet another match for Window-wasp #1. I'll need to take a closer look to be sure it's the same species, but for now I'm just concentrating on the first of these. (specimen ID 2408D)

For now I’ll restrict my focus to Wasps #1, #2 & #3.

Who are they and where did they come from?

Who are they?

Wasp #1: Arpactophilus (CRABRONIDAE: Pemphredoninae)

No wonder she was unfamiliar. This is the first member of this crabronid subfamily we have ever seen here.

Recent molecular studies indicate that the Pemphredoninae are only distantly related to more familiar crabronids such as Pison, Rhopalum, and Bembix (Sann et al. 2018). In evolutionary terms, their ancestors diverged during the Jurassic, over 150 million years ago. The Pemphredoninae are more closely related to the bees than they are to those other crabronid wasps. Indeed, the study’s authors propose elevating the group to their own family: Pemphredonidae (Sann et al. 2018).

For now, most listings still treat them as a subfamily of the Crabronidae, so that is the approach I’m taking here.

The majority of Pemphredoninae in Australia belong to the genus Arpactophilus. There are currently 22 named Australian species, and this number may more than double when all specimens in collection are described (Matthews & Naumann, 2002).

I am tentatively calling my little window-wasp #1 Arpactophilus deakinus (details on my working notes page and iNaturalist record). Morphologically she seems a good match for descriptions of that species, and location is also consistent. The type specimen of Arpactophilus deakinus was collected in Canberra, and our home forest shares many wasp species with Canberra and the wider ACT.

The images below show some of the features relevant for identification, including overall head and body shape, size, and forewing venation.

Wasps #2 & #3: Megalyra (MEGALYRIDAE)

While the Arpactophilus was an intriguing find, it was overshadowed by the discovery of wasps #2 and #3. Both are Megalyra … weird and mysterious little wasps indeed!

First, they’re rather rare. Megalyra species are only seldom encountered or collected (Shaw 1990, Vilhemsen et al. 2010a). The most recent taxonomic review of the genus uncovered only 550 specimens across 26 museums and insect repositories worldwide (Shaw 1990), and nearly half of those were of a single species (M. fasciipennis; n=262). The majority of Megalyra species were each represented by just a few specimens … in eight cases, by just one!

Second, for most species nothing is known of their biology. In part this seems a simple consequence of their rarity, but no doubt concealed larvae further confounds study of the group. More about that later.

Third, they are quite unlike most wasps. In evolutionary terms, Megalyridae is very far removed from the crabronids and sufficiently distinct from all other wasp families to be granted its own superfamiy. The Megalyroidea diverged from the ancestors of the stinging wasps during the Triassic*, over 200 million years ago (Peters et al. 2017, Vilhemson et al. 2010b)!

One of eight extant genera of the Megalyridae, Megalyra is predominantly an Australasian genus and is the only member of the family to occur in Australia (Shaw 1990). There are currently 22 named Australian species (Shaw 1990) … and two of them suddenly showed up on our window sill!

I’m convinced that wasp #2 (which has my collection code of 2406C) belongs to the minuta species-group. I have posited the species identity as Megalyra minuta (details on my working notes page). If correct, it just might be the first public record of a male of this species! But the accuracy of my ID suggestion remains to be tested, perhaps by an expert with access to a reference collection.

The larger of the two Megalyra, ‘wasp #3’ (labelled 2408B in my collection), is also a male but he clearly belongs to a different species-group. Again I’ve made a tentative ID … in this case, the wagneri species-group (details on my working notes page). He’s a good match for Megalyra wagneri, a widespread species relatively well-represented in collections.

Where are they all coming from?

Despite being closely surrounded by forest, we get surprisingly few critters inside the house. It was built to exclude embers in the event of bush fire, and as a result there are few points of entry for flying or crawling insects.

The one obvious route is the dead wood we bring inside each winter’s day for the wood stove.

Our outdoor firewood stockpile, cut to size for our small wood stove. This stash includes Eucalyptus and Angophora, mostly trees and branches that were killed in the January 2020 fire and that have dropped in the past 12 months. Many sections show signs of termite workings and fungal activity, creating a variety of galleries and openings which are often home to live termite or ant colonies. We also occasionally disturb the large larvae of longhorn beetles (Cerambycidae) when we split Eucalyptus rounds.

Each day during winter we top up the firewood buckets with another load of various sizes and 'types' (ie species) ... and no doubt whatever insects and spiders are hidden away within. As the buckets are rarely completely emptied, some pieces of wood towards the bottom may sit there a week or more (somthing that will become relevant when I consider what the wasps may have been doing inside the wood).

Many of the smaller diameter pieces are from E. sieberi. Most of these trees survived the fire and subsequently regenerated foliage from epicormic growth, but the branches of the upper canopy were universally fire-killed. Such dead limbs can remain aloft for years before a strong wind sends them flying.

The few greenish pieces in the right hand bucket are Acacia mearnsii stems from track clearing we undertook a few months ago. In parts of the forest the post-fire regrowth of wattles has been quite impressive!

The other major component is from large, dead Allocasuarina, Acacia and Hakea. All were killed outright by the January 2020 fire, yet many remained standing for years ... but lately they have started falling apace. Free firewood every time a strong wind blows!

And such pieces are typically riddled with holes and other evidence of wood-boring insects. Beetles such as Cerambycidae. Moths such as Cossidae and Hepialidae. This is the very reason we didn't immediately clear all the dead wood, post fire. Each dead shrub and tree has continued to play an important role in the ecosystem long after its own demise. Even now we gather only a fraction of the forest dead wood. The rest will gradually decay, all the while providing food and housing for others.

So what were they doing in the firewood?

Knowing who they are, I can now speculate on how they came to be in the firewood.

Arpactophilus – a predator

Borer holes and tunnels in wood are prime nesting territory for a variety of hymenopterans, including several species of Arpactophilus (Matthews & Naumann 2002). Indeed Arpactophilus deakinus nests were discovered in the stems of garden shrubs in Canberra, the wasps having taken possession of burrows previously used by other hymenopterans. It’s therefore quite possible that my Arpactophilus (wasp #1) hatched inside a silk-lined chamber within a dead wattle branch. As a growing larvae, she would have fed on psyllid nymphs regularly delivered by her attentive mother – or perhaps an aunt or older sister. Arpactophilus species range from solitary to possibly eusocial, and there is some evidence of cooperative nesting among A. deakinus (Matthews & Naumann 2002).

By the time I brought the stick inside the house, she had already transformed from larva to pupa … and was biding her time to complete her metamorphosis to adult wasp. The warmth of the house probably triggered the change, and she then crawled free of the wood and flew towards the bright light of the window. Matthews and Naumann (2002) found that “all species appear to have multiple generations per year where conditions permit” (p. 101). In Canberra, A. deakinus has two or perhaps even three generations annually (Matthews & Naumann 2002).

Of course, I postulate – but it would explain how she came to be inside the house, as an adult, in mid winter.

Megalyra – a parasite

Biological information is available for only a few species of Megalyra. The large, widespread and (relatively) common species M. fasciipennis parasitises wood-boring Cerambycidae and has been observed working over standing, dead eucalypts in NSW (Mesaglio & Shaw 2022). Indeed, most evidence points to Megalyra being parasites of immature wood-boring beetles, including Buprestidae (jewel beetles) and Cerambycidae (longhorn beetles) (Vilhemsen et al. 2010a).

So my tiny Megalyra males (wasps #2 & #3) probably hatched from eggs injected into narrow, frass-filled tunnels in dead branches or tree trunks. On hatching, they fed on the resident beetle grub and eventually pupated within the tunnel … to emerge after the branches were brought inside for firewood.

However, there is a second possibility.

There is one known exception to the general rule of Megalyra as parasites of beetle larvae … and it is curiously relevant to this story. In the far north of Australia, the tiny Megalyra troglodytes attacks crabronid wasp larvae (Naumann 1987). And not just any old crabronid, but Arpactophilus! Hhhhhmmm. Perhaps my Megalyra grew up inside the Arpactophilus nests, at the expense of the crabronid host. Maybe, just maybe.

Valuing dead wood

Each time I put another stick on the fire I now feel a small twinge of guilt. Is the wood currently home to various small, developing insects? Quite likely. But to assuage my conscience I only need take a short walk in our home forest. Standing dead trees. Fallen branches and logs. Ample food and accommodation for wasps, beetles, bees, moths and more … now, and for generations to come.

References

Mesaglio, T. & Shaw, S.R. 2022. Observations of oviposition behaviour in the long-tailed wasp Megalyra fasciipennis Westwood, 1832 (Hymenoptera: Megalyridae). Austral Ecology, 47(4): 889-893 open access https://doi.org/10.1111/aec.13163

Matthews, R.W. & Naumann, I.D. 2002. Descriptions and biology of nine new species of Arpactophilus (Hymenoptera: Crabronidae), with a key to described Australian species. Journal of Hymenopteran Research 11(1): 101-133 freely available from BHL

Naumann, I.D. 1987. A new megalyrid (Hymenoptera: Megalyridae) parasitic on a sphecid wasp in Australia. Journal of the Australian Entomological Society 26: 215-222

Peters R.S., Krogmann L., Mayer C., Donath A., Gunkel S., Meusemann K., Kozlov A., Podsiadlowski L., Petersen M., Lanfear R., Diez P.A., Heraty J., Kjer K.M., Klopfstein S., Meier R., Polidori C., Schmitt T., Liu S., Zhou X., Wappler T., Rust J., Misof B., Niehuis O. 2017. Evolutionary History of the Hymenoptera. Current Biology. Apr 3; 27(7):1013-1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.027. Epub 2017 Mar 23. PMID: 28343967 - open access

Sann, M., Niehuis, O., Peters, R.S., Mayer, C., Kozlov, A., Podsiadlowski, L., Bank, S., Meusemann, K., Misof, B., Bleidorn, C., & Ohl, M. 2018. Phylogenomic analysis of Apoidea sheds new light on the sister group of bees. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 18, 71

Shaw, S.R. 1990. A taxonomic revision of the long-tailed wasps of the genus Megalyra Westwood (Hymenoptera: Megalyridae). Invertebrate Taxonomy 3: 1005-1052

Vilhemsen, L., Perrichot, V., & Shaw, S.R. 2010a. Past and present diversity and distribution in the parasitic wasp family Megalyridae (Hymenoptera). Systematic Entomology, 35: 658-677

Vilhemsen, L., Mikó, I. & Krogmann, L. 2010b. Beyond the wasp-waist: structural diversity and phylogenetic significance of the mesosoma in apocritan wasps (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 159: 22-194

*Note: Peters et al. 2017 were not able to obtain DNA from Megalyridae, so did not sample this family directly. However, Vilhelmsen et al. 2010b had previously demonstrated a close relationship between Megalyridae, Trigonaloidea and Evanioidea based on structural similarities.