Uncovering hidden wasps

New things can turn up in the most unexpected places. I recently found what for a naturalist is perhaps the ultimate new thing - a species previously unknown to Science!

The way in which I discovered this creature, a tiny parasitic wasp called Cotesia wonboynensis, was totally surprising. It was hiding away inside the body of what had been my original object of interest - a caterpillar.

Many wasps are endoparasites

It takes a lot of energy and materials to assemble an organism from scratch. Animals use a variety of strategies to supply the necessary resources to their developing offspring. One of these strategies is to place your egg, embryo or larva in a place where it can feed off the nutrients supplied by someone else.

Many animals choose this ‘bludging’ method, where their offspring lives as an endoparasite inside the body of another organism. This approach is widely used, in a variety of ways, by wasps.

Some parasitic wasps sting an adult animal, such a spider, and deposit an egg in or on its temporarily immobilised body. The host recovers but becomes a living, moving food source to support the development of the wasp larva growing within.

Other wasps choose a larva or nymph rather than an adult animal as a host for their developing young. The female wasp lays one or more eggs inside the body of the host, which is initially little affected. The host goes about its business, feeding and growing, while the wasp larvae that hatch out of the eggs secretly nourish themselves from its body fluids.

Eventually the endoparasites start to devour the body tissues of the host, leading to its demise. The wasps exit the body of the deceased host either as a larva or a fully-formed adult.

In all of these cases, the developing wasp remains hidden inside its host - be that an egg, larva or adult - until it finally emerges. If you are monitoring the development of an insect that has been thus parasitised, you may be in for a surprise, as the following story illustrates.

The She-oak buddy

My story begins not with a wasp, but with an unfamiliar caterpillar, which we found on 8th February this year on the foliage of a Black She-oak (Allocasuarina littoralis) tree. As with everything we find in our patch of forest, we were curious to know the identity of this caterpillar.

Identifying a moth from its larva can be very challenging. Caterpillars of related moth species tend to look alike, even when the adults are quite distinctive. And the larvae of only a fraction of the >10,000 Australian moth species have yet been identified and photographed.

For this reason, we generally try to rear caterpillars that are unknown to us through to the adult stage. We put them in a terrarium (affectionately known as the Buddy Tank) with what we guess is their favoured food, watch and wait.

Our new caterpillar took to its new surroundings in the Buddy Tank well and fed happily on the supplied casuarina cuttings.

It grew apace, as shown in the following image sequence.

Then a month later - on 7th March - its behaviour suddenly changed. It became restless, wandering around the tank before finally resting on the floor. We wondered whether it was about to pupate, as this sort of behaviour is often seen just before a lepidopteran larva makes a cocoon and undergoes metamorphosis.

But 9 days later we found the caterpillar lying motionless on the floor of the tank. We presumed it had died and that the white fuzzy material we could see on its back was some sort of fungus.

Closer inspection revealed that yes, the caterpillar was dead.

But the stuff on its back was actually a collection of about 30 cigar-shaped silken cocoons. Intriguing!

Wasps enter the picture

Kerri had the presence of mind to cover the caterpillar corpse with a glass, to trap anything that might emerge from these cocoons.

This was a good move, because at 6pm on 24th March - just 8 days after we first noticed the cocoons - she spied two tiny wasps, only about 3mm long, crawling up the inside of the glass.

By the next morning several more wasps had emerged from their cocoons. Two days later we had a collection of 30 young wasps - the complete brood - inside the glass.

Close examination of the cocoons revealed the little trapdoors used by the wasps to make their escape.

20 of these wasps were clearly females, as they possessed an ovipositor, shown in the images below. The other 10 lacked this organ, so were males.

What sort of wasp?

Identification of wasps, like moth larvae, is a non-trivial process. They belong to the order Hymenoptera, which is one of the four mega-diverse orders of insects. There are 57 families of Australian wasps (63 if you include the sawflies). So even getting to the family level can be challenging.

Flicking through the tome Insects of Australia (Naumann, 1991), I chanced across a drawing of a wasp that looked very similar to our parasite.

Fig. 42.20E from Ref. 1

This is a member of the family Braconidae, sub-family Microgastrinae, which according to Insects of Australia, “are endoparasites on larvae of Lepidoptera” (Naumann, 1991 p.949)- tick.

Naumann continues… “Oviposition is into the egg or early larval instar. Pupation takes place outside the host, gregarious species often spinning their cocoons together in a silken web.” - tick.

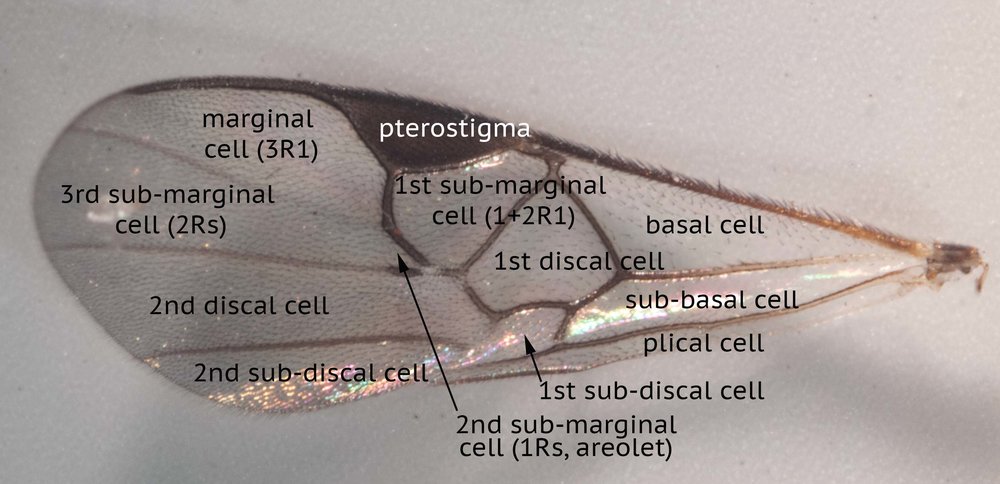

Close examination of the body of my wasps convinced me that they belong to the subfamily Microgastrinae. Some of the defining characters are shown in the images of the wings, head and antennae below.

Microgastrinae is one of the largest subfamilies in the Braconidae, with around 1,300 described species worldwide. Australia has 100+ described species, which probably represents less than 20% of its true size.

Being endoparasites of lepidopteran larvae, these wasps are important agents for biological control of agricultural pests. They have been used to control lightbrown apple moth, potato moth, cabbage moth, budworms, armyworms and cutworms. In a natural environment, they undoubtedly help to maintain the ecological balance - keeping populations of various moth larvae in check.

Which genus of microgastrine wasp?

So where to next? The Australian Faunal Directory led me to a paper (Austin & Dangerfield, 1992) with a key to genera in the subfamily Microgastrinae. But despite spending several hours closely examining body parts, I couldn’t pin down the genus.

Some time after my discovery of these wasps, I was told about a researcher Dr. Erinn Fagan-Jeffries, from the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Adelaide, whose area of expertise is the taxonomy of microgastrine wasps. Erinn is very keen to receive wasps of this type that emerge from caterpillars or any other insect larvae as many of the hosts for microgastrine wasps are unknown.

Erinn kindly offered to DNA barcode my wasps to establish their identity. I mailed several off to her and a while later she emailed with the news that they belong to the genus Cotesia. Worldwide, this is the largest genus of microgastrine wasps and is the second largest Australian genus.

Which species of Cotesia wasp?

After further analysis, Erinn was confident that my wasps were a new, native species of Cotesia and included it in a revision she was preparing of that genus. Exciting! She gave me the chance to choose the name of this new species and I suggested wonboyn, the name of our local village.

Enter Cotesia wonboynensis, the Wonboyn Wasp! This has now appeared in a published scientific paper (Fagan-Jeffries & Austin, 2020).

Back to the beginning - what is the caterpillar?

This story began with a caterpillar. This seems to have been forgotten along the way.

While I have learnt a lot about wasp biology and taxonomy, I’m still not sure what species of moth would this larva have developed into had it not been parasitised by a female microgastrine wasp.

A good candidate is Anthela connexa. This species is reported to feed on Casuarina and Allocasuarina (Marriott, 2012) and an image on Don Herbison-Evan’s website is similar to my caterpillar.

References:

Austin, A.D. & Dangerfield, P.C. (1992) “Synopsis of Australian Microgastrinae (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), with a key to genera and description of new taxa”. Invertebrate Taxonomy 6: 1-76.

Fagan-Jeffries, E.P. & Austin, A.D. (2020) “Synopsis of the parasitoid wasp genus Cotesia Cameron, 1891(Hymenoptera: Braconidae: Microgastrinae) in Australia, with the description of seven new species”. European Journal of Taxonomy 667: 1-70. open access https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.667

Marriott, P. (2012) “Moths of Victoria Part 1. Silk Moths and Allies” 2nd edition. Entomological Society of Victoria.

Naumann, I.D. (1991) Chpt. 42 Hymenoptera (Wasps, Bees, Ants, Sawflies) pp. 916-1000 in The Insects of Australia. 2nd Ed. CSIRO Melbourne University Press.