20/11/2022 (14:45)

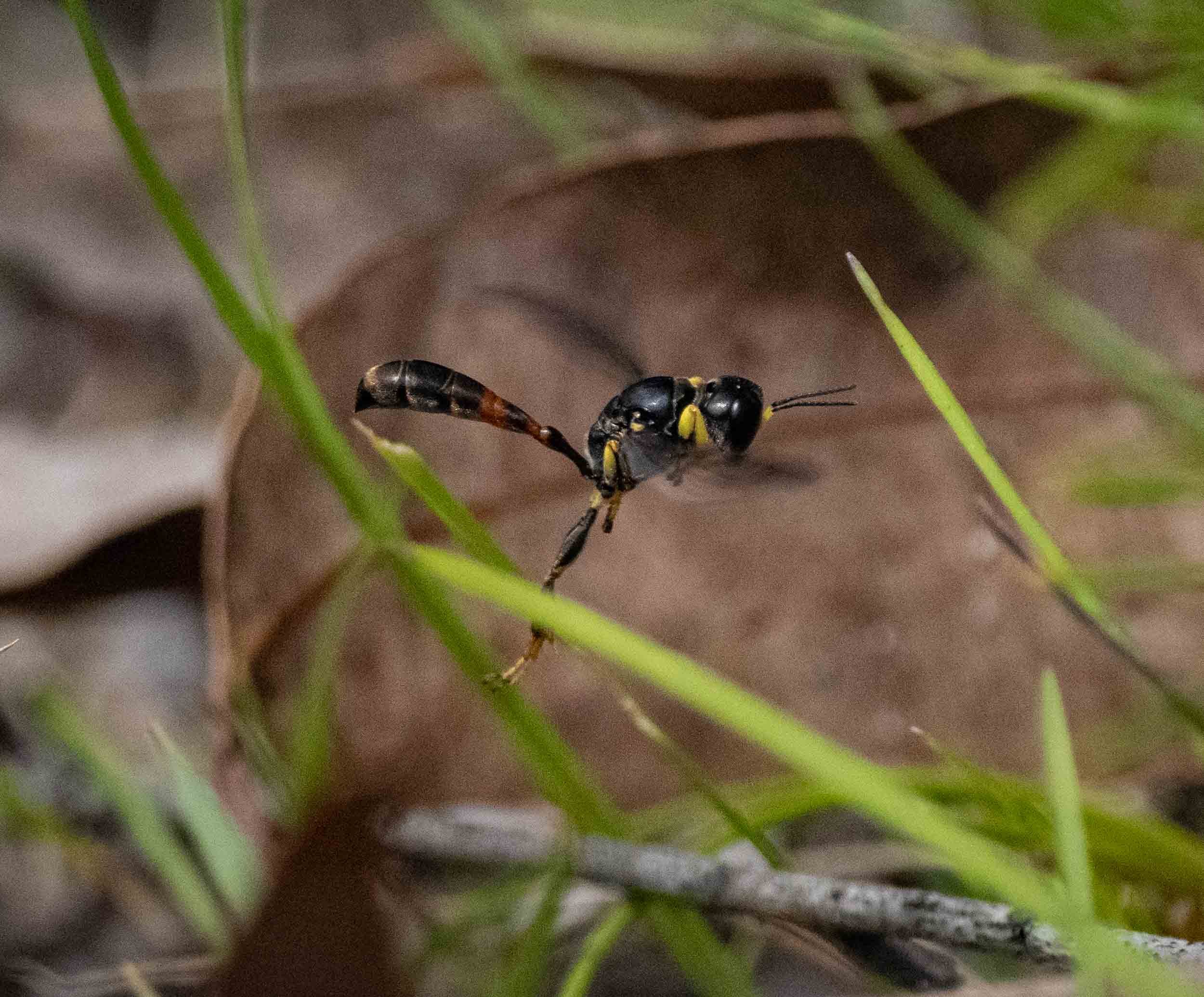

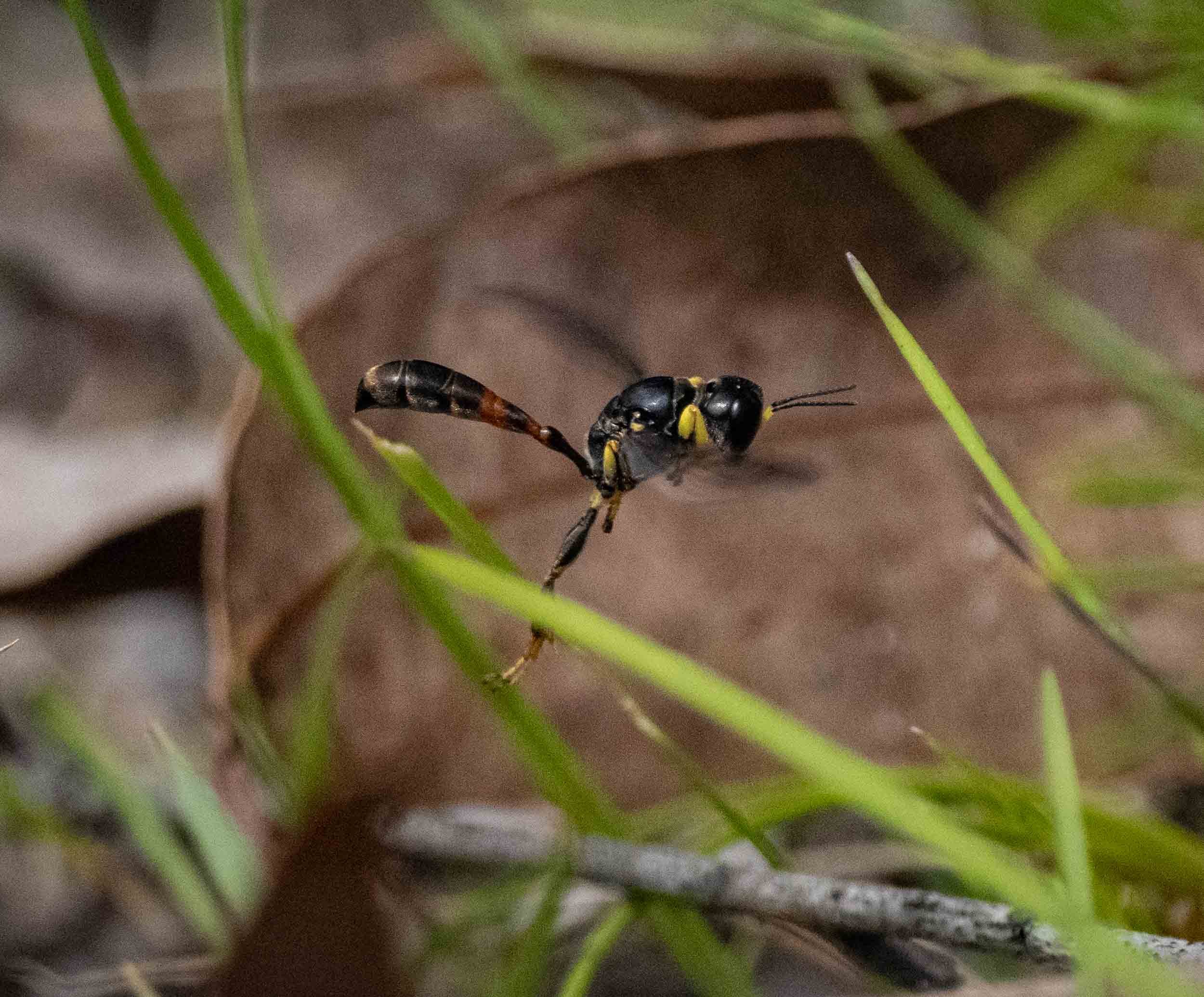

a distinctive crabronid

Podagritus are quite easily recognised. The narrow ‘petiole’ at the base of the abdomen is a clue, along with their relatively large size.

bobbing flight, dangling legs

Insect-spotting is a bit like bird-spotting. With practice, you learn to recognise a species by its general shape and the way it moves. For me, the long dangling legs and the bobbing flight close to the ground say “Podagritus” … or perhaps “Rhopalum”, if it’s a tiny insect.

relatively large

Compared with the tiny, cryptic Rhopalum I was watching in August - September (click to read earlier post), Podagritus are large and obvious. The two genera are otherwise similar and closely related.

high density housing

Podagritus favour sandy soil, in the sun, and with some vegetation cover. I never find them nesting out in the middle of a track. And they seem to like high density life. Their burrows are sometimes very close together, the mounds overlapping.

[The burrow openings are 5mm in diameter. Contrast this with the burrows of Rhopalum coriolum, which measured just 2mm. This Podagritus species is a much larger insect.]

a rare chance to see her prey up close

Typically, prey-laden Podagritus females fly in slowly, then quickly dive into their open nests. Only occasionally will one land on vegetation … and so afford me a chance to see exactly what she’s carrying and how. Note how she uses her middle legs to grip the fly. This is quite stereotypic behaviour among Podagritus. Other wasps use different methods.

stiletto flies a favoured food

In previous years, these large Anabarynchus flies were the prey I’d most often see Podagritus carrying. This year there do not seem so many of these flies around, so perhaps the wasps are having to work harder … or diversify.

a lost nest

It is not uncommon for a returning wasp to apparently ‘lose’ her nest. Sometimes the entrance has been covered by blown leaf litter or collapsed by animal traffic. This Podagritus female put aside her prey (visible just under the leaf) while she scraped the soil in search of her burrow.

a fruitless search

Agitated and clearly searching for her nest, she tried an aerial view. No luck. She eventually flew off, abandoning her prey - the fly lodged just under the edge of the leaf.

snipe flies also acceptable

Note that this fly is much smaller than the Anabarynchus more typically gathered. It’s a snipe fly, probably Chrysopilus (RHAGIONIDAE). And paralysed, not dead. I know because I collected it for a closer look (robbing the ants of a free meal). Even 24 hours later it would still give an occasional twitch.

[Interestingly, I have found no previous mention of this fly family among the prey listed for Podagritus. TACHINIDAE and THEREVIDAE are their reported targets, at least for the few species of Podagritus that have been studied.]

'do they sting?'

This is perhaps the most commonly asked question when it comes to wasps. Podagritus does have a sting. They use it to paralyse their prey and will use it in defence, if desperate. But like most solitary wasps, they are not aggressive. They can’t afford to risk their lives attacking potential threats (such as a person lurking nearby with her camera). They have a nest to stock, and eggs to lay! People tend to be stung by social wasps, and even then only when their nest is threatened.

early nest, flat mound

By early November there were already large numbers of Cerceris nests. Little yellow faces peering out from low mounds, both in the open of the path and among sparse vegetation nearby. It may be some of these wasps overwintered as adults within these very tunnels! They may have even mated last April, and so been ready to start nesting immediately (Evans & Matthews 1970).

a growing mound

Over time, as the wasps carve out more tunnels and chambers, the pile of sand around the opening can form quite a large mound. Not all the excavated sand is ejected from the opening. Some of it is simply moved out of the nest chamber and forms loose plugs through which the wasps dig when ready to move onto the next cell (Bohart & Menke 1976).

distinctive wasps

Cerceris are readily distinguished from most other crabronid wasps. The grooved abdomen, rounded ‘petiole’ and wide head are distinctive.

alert and responsive

Like most wasps, Cerceris have good vision and are alert to movement and changes in their environment. She certainly seems aware of me … watching her, watching me.

guard duty

An inquisitive ant takes one look at those mandibles and quickly retreats. The mandibles are largely for digging, but they do look rather intimidating. Note that by withdrawing slightly into the burrow, the wasp’s large head effectively blocks the entrance.

wary return to her nest

Most prey-laden Cerceris fly directly to their nest mound and rapidly scramble inside. But sometimes I get lucky and one will briefly land on nearby vegetation. It seems that for every 20 returning hunters I see, I have the chance to photograph just one or two. At times I sense they are well aware of me and my camera.

beetle prey

Cerceris feed their larvae on paralysed beetles. This looks like a leaf beetle (CHRYSOMELIDAE), possibly Edusella or another in the subfamily Eumolpinae. Such beetles are quite common here in the forest at the moment, and Edusella are common prey of Cerceris in south-eastern Australia (Evans & Matthews 1970).

a mouthful of antennae

This female is showing the classic Cerceris prey hold … grasping the paralysed beetle’s antennae with her mandibles. She also uses her front and middle legs when in flight (Evans & Matthews 1970).

Note the rather small size of her catch. Cerceris prey upon beetles of various sizes.

hairy and a particular 'jizz'

After an intense couple of weeks insect-spotting in this small patch, I’m getting quite good at spotting male mutillids. They’re hairier than most flower wasps, and they fly in a rather characteristic way. This one perched briefly alongside the path, apparently on the lookout for a female.

investigating the path

Most males I see are perched nearby, but occasionally one will come to ground and investigate. Note the busy antennae, tapping and stroking the sand and leaf litter.

another male on the lookout

Yet another male velvet ant visiting the path. This one was particularly blue … perhaps a different species again. Mutillids are notoriously difficult to study and as a result there are no doubt large numbers of undescribed species and the taxonomy of the group is contested.

a rare sighting ...

One morning I spotted this male as he landed, clearly carrying a load. I was witness to something very rarely seen … mating velvet ants! He is not a large insect (for scale, the stem he’s clinging to is just 1mm wide) but she is smaller still. During the coupling, she was securely held within the curve of his body. It was all over quite quickly … in stark contrast to the protracted pairing of thynnine flower wasps.

... mating velvet ants

The sexes of a single species often look nothing alike. Males are larger and winged … but even the colours can be wildly different. In this shot the pair had just uncoupled. Moments later the male flew off and the female climbed down the grass stem and scurried away … probably back to the path, immediately alongside.

one of many females

Female velvet ants scurrying about the open path area are a common sight of late. Their antennae are constantly on the move, tapping small stones and sand grains, occasionally probing between them.

the most numerous species

Females with red legs and two golden felt bands on the abdomen are the most abundant type. Whether these are all the same species or not, it’s impossible to tell. What I can be confident of is that they were born nearby … perhaps emerging from this very patch of sand.

probing holes and burrows

Something beneath this stick had clearly attracted the interest of this female mutillid. She pushed and probed and at one stage nearly disappeared from view before departing to investigate various nest mounds nearby. Later I lifted the stick aside and discovered a nest hole. The owner? Unknown at this stage.

a completed Sericophorus nest

This nest was collapsed and abandoned by the owner - a large Sericophorus female – nine days earlier. The mutillid was clearly interested, although she didn’t stay long. I had seen her (or some other female velvet ant) do the same thing several times. Perhaps she/they are monitoring the development of the Sericophorus larvae … although I don’t know how they could do this. The nest chambers are likely to be well below ground.

an active but closed Sericophorus nest

This is another of the Sericophorus nests, but this one an active nest. It would be complete and ‘backfilled’ two days later, but at the time of this mutillid’s visit the owner was inside. As they do during much of the day, Sericophorus had plugged the burrow with soil … so perhaps that is what deterred the mutillid, which soon backed out and wandered off.

an active, 'open' Cerceris nest

Cerceris nests often have a wasp guarding the door … but not always. This female mutillid ventured across the threshold unchallenged. The nest looks wide open, but apparently Cerceris blocks the tunnels further down. The owner may have been out hunting, but she may have been well below ground, excavating a chamber and stocking it from her stash. Whatever the reason, conditions weren’t right and the visiting mutillid soon moved on.

another fruitless visit

Despite many hours of observation, I have yet to witness a fruitful nest visit by a velvet ant. I would expect her to disappear down the burrow, locate and access a chamber containing a late stage larva/pupa, deposit an egg, and climb or dig her way out again. All I have seen is the mutillids taking a quick ‘peek’ before departing. I guess they’re still waiting for the larvae to develop.

a rarely studied Australian endemic

Austrogorytes are robust and rather fierce looking wasps, but they are actually rather reclusive and shy. Unlike Bembix, their near relatives, little is known about their behaviour. I rely upon the 1970’s work of Howard Evans and Robert Matthews (1971b) in and around Canberra to provide insights into their nesting biology.

drag, kick .. drag, kick

Austrogorytes has her own particular digging style. The front legs are equipped with rakes, rows of long spines. Using both in synchrony, she drags armloads of sand and soil from the burrow as she walks backwards. Then the back legs take over, and kick the sand away. It results in a characteristic jerky, highly effective display.

a long sloping burrow

The burrow entrance is clearly at an angle, not vertical. And it is likely to continue to slope inward for 15-30cm, with a cluster of side branches leading to the actual nesting cells (Evans & Matthews 1971b).

leafhopper specialists

As in the Canberra population (Evans & Matthews 1971b), our local Austrogorytes stock their burrows with leafhoppers. These little sap-sucking bugs are common in the area, the growing colonies of nymphs and adults feeding on eucalypt saplings … always with attendant ants. Obviously the ants are not an effective deterrent to these foraging wasps.

males patrol the patch

One of the first Bembix to appear in mid November, a male. He flies back and forth along the path, on patrol, landing occasionally. No doubt the males are waiting for females to appear … perhaps from the sands beneath their feet. Bembix nest gregariously and use the same patch year after year (Bohart & Menke 1976).

an access ramp

Within a few days of making their first appearance, Bembix females were digging burrows. They apparently mate just once, soon after emerging (Evans & O’Neill 2007). Note the sloping entrance, quite different to the near vertical shafts constructed by Podagritus and Cerceris.

females have impressive front legs

This female is demonstrating classic Bembix digging stance: front legs splayed sideways with the tarsi curled inward, those impressive rakes at the ready. Oh, and her equally impressive mandibles.

rapid sand raking

Burrowing by Bembix is fast, furious, and noisy. The front legs scoop loads of sand and cast them out behind the buzzing wasp. It’s not discreet, but it is fast – and perhaps it needs to be. She scrapes sand back into the entrance when she leaves, and so must dig her way back through the closed and concealed ‘door’ each time she returns with prey.

cryptic nests

There is little to mark the site of a Bembix nest. This one was unusually obvious as the freshly moved sand was wet. Within minutes it would blend in, as it dried and the wind scattered the finer particles.

open ground

The middle of the path is hot property, as far as the Bembix are concerned. I have yet to see them at work on the fringes or amongst the scattered grasses and herbs nearby.

males seek virgin females

Two weeks since they first appeared, and males are still around. The peak of male emergence precedes that of females … which makes sense. Females only mate once, so males that are on the scene the moment a virgin female emerges from the soil are the most likely to be successful. They can detect females through several cm of sand, and will scrape at patches where they predict a female may emerge (reviewed in Evans & O’Neil 2007). Mistakes are made – sometimes they unearth a male or another species entirely – but it’s a strategy that can work. And maybe that is what the male in this photo was doing, ‘sniffing out’ a potential mate.

my first sighting

Mid afternoon on 13th November I spotted this stocky, metallic wasp mid track. I had not seen anything like her before!

early earthworks

After scraping briefly at a few sites along the path, she chose one toward toward the edge and got to work in earnest. The site itself was free of vegetation, but close enough that I’m sure there would have been fine underground roots to contend with, along with quartz pebbles of various sizes.

[wasp A: 13th Nov, 2pm]

a castle built in just 4 nights

Soon the Sericophorus nest is impossible to miss. A large, rather messy pile of sand with an ill-defined opening to a vertical entrance.

[wasp A: 17th Nov, 8:40am]

closed for the day

I rarely see the wasp, as by 9am she has typically shut down for the day. She may be busy inside, storing her catch, but there is little activity above ground.

[wasp A: 17th Nov, 9:16am]

unexpected daytime action

One morning I noticed unusual activity at the second of the Sericophorus mounds (‘nest B’). Middle of the day, and the female was busy at the nest opening. It soon become obvious that she was dismantling the mound! Using her mandibles and her legs, she dislodged the sand and pebbles, letting them fall down into the burrow behind her. Occasionally she would disappear inside, but soon she’d return and just keep digging.

[wasp B: 18th Nov, 11:37am]

nest B shut down

Having eroded the top of the mound, and so apparently ‘back-filled’ the entrance burrow, she abandoned the nest (just 2 minutes after this photo). She did return once, 20 minutes later, but after a brief check of the mound she started scraping at various other parts of the path … presumably seeking a suitable site for a new nest.

[wasp B: 18th Nov, 12:08pm]

building site check

Having collapsed the opening to her original nest, Wasp B seemed intent on finding a new location … nearby. All the while the burrow to Nest A remained closed, as usual for the middle of the day.

[wasp B: 18th Nov, 12:32pm]

another building site check

Wasp B continued searching the path. Occasionally she would revisit her old mound, but not for long. At this stage I wondered if something had gone wrong. Why would she abandon her nest just a few days after building it?

[wasp B: 18th Nov, 2:04pm]

mound closure is normal behaviour

The puzzle of Wasp B’s behaviour was solved when, a few days later, Wasp A did exactly the same thing! She systematically eroded the rim of her nest mound, allowing the rubble to fall back down the burrow. None of it was ejected out onto the mound … she was clearly intent on blocking the nest tunnels.

[Wasp A: 21st Nov, 12:35pm]

a new nest?

A few days after Nest B was abandoned, a new hole appeared alongside … just 30mm away from the old opening. After another week, there is yet another hole, again immediately alongside. Curious! Perhaps Wasp B has rebuilt … although there is no apparent mound. Another mystery, for another day.

a tiny, unfamiliar wasp

I was on the lookout for Sphodrotes when I spotted this tiny, red-legged wasp.

[8th Nov, 12:42pm]

clearly searching for her nest

Dragging immobile prey, this was evidently a sand-nesting female searching for her burrow. She was searching a walking track, and there’s every chance that we had disturbed her landmarks (or even trodden on her nest!) in passing.

her prey is a small fly

The wasp was small, her prey even smaller. It’s a fly … two wings plus obvious halteres. The wasp grips it with her back legs as she clambers over fallen sticks.

fruitless searching

She kept returning to this spot, so presumably her nest was close by … in an open, sandy patch without any covering vegetation.

abandoned prey up for grabs

An hour later I returned to the same spot, hoping for a better look at the mystery wasp. She was still around, occasionally peering out from beneath a dead leaf, but she had given up on her fly. As so often happens to unattended wasp prey, an opportunistic ant was already at work dragging it away.

a newcomer to the neighbourhood

This was my first sighting of this species in the ‘neighbourhood’ patch I’ve been monitoring all month. And it took me a moment to realise it was the same as the mysterious, tiny wasp I’d previouly seen elsewhere, hauling a fly.

nesting or mate seeking?

I’m not sure if it is male or female. It could be a female looking for a nest site. Equally, it might be a male seeking an emerging female. Either way, that makes the path a nesting patch for this species … potentially, at the very least.

the tiniest crabronid on the block

Alongside such a small wasp, the coarse sand of the path looks like a boulder field.

bigger than an ant, but not by much

a low, wide mound

Lipotriches mounds have a 4mm wide, central opening … often with a pair of protruding antennae. The mound itself is about 50mm in diameter, and roughly circular.

someone collapsed the nest!

Lipotriches usually drop straight down into their open burrow when they return to the nest. Not this time. I guess something (or perhaps someone) had stepped on the nest. I rather guiltily took advantage of the situation to grab some shots of her at work.

unplanned digging

She spent some time opening the door, but I’m pleased to say she was successful. This was on 14th November, and that same nest is still intact and active today (2nd December). So all ended well.

all is well after the nest collapse

This is the same nest which had been collapsed 4 days earlier. It may be the same bee that I saw doing the digging, or it might be a nest mate. This species has been described as communal or even semi-social – that is, with some division of labour (Wcislo & Engel 1996). All I can say from my own observations is that there is often a bee on guard duty!

a well-build, guarded entry way

In comparison to the nests of nearby wasps, I was struck by the regular and compacted appearance of the Lipotriches burrow walls. More like a concrete pipe than a sand burrow. This may be related to the fact that the bees never seem to block the door with sand. Whenever I check the nests, they are wide open … with a golden head and large eyes filling the space.