Autumn pond audit

Recently we completely refurbished the frog pond. Rolled away the rocks, drained the water, removed the plants and coarse sand – all the while on the lookout for displaced animals. Given the fire-damaged state of the pond, we were pleasantly surprised by what we found.

The frogs, spiders, insects and crustaceans shown below were all living in the pond or amongst the wet gravel and rocks at the water’s edge. Most were carefully removed and replaced the next day, into the rejuvenated pond. There were some exceptions, including the spiders which scurried away and will no doubt find their own way back.

Breeding, hunting and grazing:

three stories from the pond

Breeding frogs

The first time I saw a brood frog was in May 2018 – a female Pseudophryne dendyi with bulging belly, sitting alongside the pond at night (see this 2018 post). I wondered then if we might someday find a nest of eggs nearby …

… and last month we did! Several nests in fact, and several frogs too. I was moving rocks as we prepared to deconstruct the fire-damaged pond, and there they were. Hundreds of gleaming eggs amongst the sand grains well above the waterline. They looked like pearls, silver and shining. The embryos with their black eyes, transparent tails, bulging white bellies, and their flickering movement as they flexed and wiggled inside their watery globes. Wonderful little packets of life.

Species identification was easy … two egg clusters were attended by adult frogs. Both were males, hunkered down unmoving amongst the gravel and eggs. The third frog was a female, sheltering beneath a rock but with no eggs nearby.

So what’s their story?

The adult frogs were lucky survivors of the fire. They just happened to be somewhere safe on January 5th – such as under the rocks or in the damp soil around the pond. They certainly could not have been far away – they are small and don’t walk far or fast – and everything nearby was completely burnt out. Less fortunate individuals would have been caught out in the forest, clambering amongst the leaf litter in search of ants, termites and other invertebrates. Such is the normal behaviour of this species during the non-breeding season (White, 2017).

Perhaps post fire they went off hunting again but now they are back at the pond to breed. The males would have returned to the pond first, in February or March. Each selected a nest site and then started calling. The females arrived a week or so later, their bellies swollen with eggs. They followed the calls and inspected the prospective sites. The resident male fertilised her eggs as she released them onto the sand. Nest choice was mate choice. The jelly coat of each egg swelled as it absorbed water from the ground or released by the female. Sand grains stuck to the outside. And soon embryonic development was underway within.

A single nest may hold nearly 200 of ‘his' eggs. After releasing 70 or more eggs the female left the nest but the male stayed on. He continued to call, night after night. The nest gradually filled with eggs, produced by the same female or others. He stayed primarily because the nest attracted receptive females, not because he was necessary for the survival of his clutch (Woodruff, 1977).

The embryos develop in 5-6 weeks … but wait for a flood before hatching. The eggs I discovered were of varying ages, and many were ready to hatch. I know this because when I submerged a few, the tiny tadpoles quickly broke free. But if I had not disturbed them they would have slowed their metabolism (Seymour & Bradford, 1987) and waited until the next big rains filled the pond to overflowing.

Collection and release

We were pulling the pond apart completely, which meant destroying the nests. I carefully collected the frogs and the eggs into buckets for safe keeping while we dismantled their home. The frogs I returned to the rebuilt pond two days later, but the eggs I kept a little longer. I didn’t feel qualified to rebuild a suitable nest. Instead, I kept them for a couple of weeks, allowing them more time to develop before releasing them into the pond.

Fishing spiders

Dolomedes are large, long-legged spiders that can walk on water and can even hunt underwater. We disturbed two of these rather attractive animals as we moved the rocks and sand from the edge of the pond.

So what’s their story?

Fishing spiders are among the pond’s top predators. Dolomedes and other spiders in the family Pisauridae are known to feed on tadpoles and even small frogs, so it’s little surprise to find them where we did.

They sit at the edge with their front legs touching the surface of the water. They sense the struggles of terrestrial insects that fall into the water. And aquatic inhabitants are vulnerable too, with the spiders able to dive under water while breathing air trapped between the dense hairs beneath the abdomen.

The taxonomy of the family is poorly resolved, so at this stage I’m calling both of these Dolomedes sp. They differed in colour and size, so may even represent two distinct species. Or perhaps it’s just a sex and age difference. Either way, I do find them quite beautiful. And it’s good to know they’ve made our pond their home.

Dolomedes are normally nocturnal hunters and these two seemed rather surprised to find themselves out in daylight. They were quite cooperative photographic subjects and had to be ushered out of the way so that we could continue our renovations.

With the pond now rebuilt I’m sure they’ll return to the water edge.

Grazing crustaceans

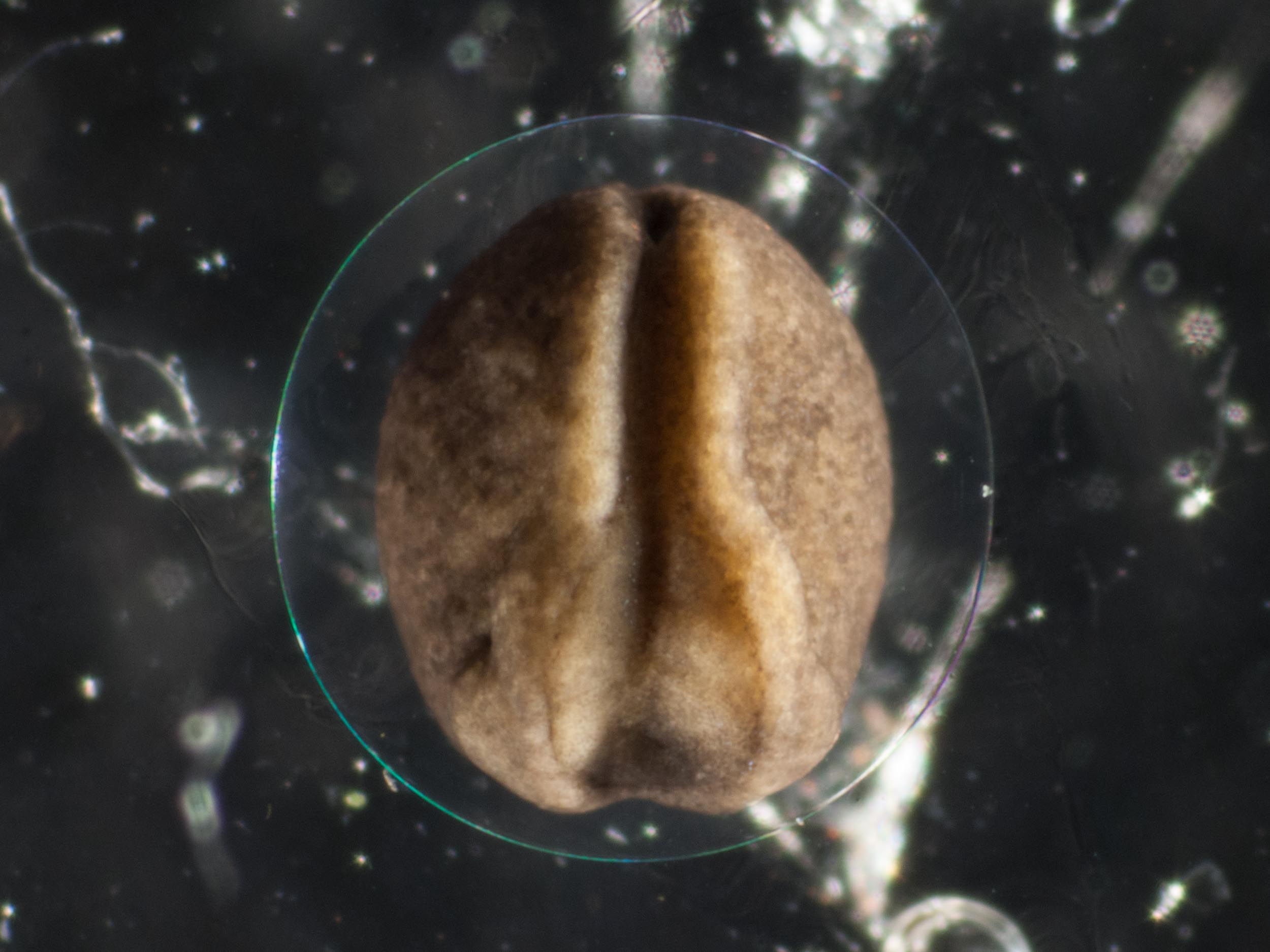

Any sample of leaf litter and detritus from a freshwater pond will yield microscopic delights. I spotted the Seed Shrimps looking like little coloured balls swimming about in the water and muck we collected from the pond. They are tiny – just visible to the naked eye at about a millimetre long.

So what’s their story?

The ‘shell’ looks rather like a bivalve mollusc, but these animals are actually crustaceans. They are in a class of their own, Ostracods, quite separate from the shrimps, crabs, isopods and amphipods (class Malacostraca) and the barnacles (class Cirrepedia). And they really are quite weird little animals.

The shell is actually the carapace, extended and wrapped around to enclose the rest of the body. And the rest of the body is nearly all head, with large antennae that it uses for swimming and for gathering food.

This little animal relies upon sensory hairs on the carapace and antennae to feel and taste its way around the pond. It also has a simple eye – a cluster of a few light-sensitive cells.

Dorsal view of freshwater ostracod, resting on a leaf

This is the first time I’ve looked at one up close and though about their existence. We probably introduced them to the pond with vegetation when we first set it up. And they’ve probably been successfully scavenging through the detritus and algae ever since.

They’re now back in the pond, returned with plants and the handfuls of detritus we put back to ‘seed’ the new ecosystem.

Notable absentees

Perhaps we missed some animals as we laboured to rebuild the pond. But we did collect leaf litter and checked the water we were baling out. I think it was a survey was more thorough than any we’ve done before. So how did it compare?

Most notable was the absence of damselflies and caddisfly larvae. I didn’t find a single one. And I would have expected to – in the past they’ve been among the most numerous of the pond insects.

The damselfly larvae are probably missing because the adults have not returned since the fire. We’ve seen some of the larger, common dragonfly species visiting the pond and surrounding area but no damselflies.

The missing caddisflies may have more to do with water quality. Trichoptera have a SIGNAL score of 8, where 1 is the least sensitive and 10 the most sensitive to water quality. The ash-laden water of the pond really didn’t look or smell particularly healthy.

The history of the pond

Our frog pond is a built environment. Water does not naturally pool at the site. There is no adjacent creek or wetland. The pond only exists because we created it.

This is at odds with our approach to the rest of the forest environment. In the forest we let nature rule without deliberate interference from us.

Less than two years after its construction, the pond is ensconced within the forest (March, 2018)

So why build a pond?

I confess, we were simply curious. We wondered what might move in. Importantly, we reasoned that the pond would do little harm. It is immediately adjacent to our house, which we figured has a greater disruptive influence on the natural environment than would one small pond.

So in 2016 we created a pond. We dug a small depression, lined it with rubber sheeting, surrounded it with rocks, and added some river sand and potted reeds. Then we simply filled it with rainwater, sat back and watched.

Newly built pond, 7th August, 2016

The pond has been an ongoing source of wonder, attracting a diverse array of residents and visitors. Frogs of various kinds (Crinia signifera, Limnodynastes peronii, Litoria ewingii, Litoria peronii, as wall as Pseudophryne dendyi). More than a dozen species of dragonflies and damselflies. Water beetles, water bugs, and a myriad of much tinier invertebrates.

No doubt some of the smallest animals originally arrived with the plants and sand we introduced in 2016. But most of the insects, frogs, and spiders that we’ve recorded over the years have simply moved in from elsewhere. Insects such as dragonflies, bugs, beetles and midges just fly in. The frogs seek out water to breed but otherwise live among the grasses and even high in the trees. Water spiders probably drift in as tiny spiderlings, blown from afar on long silken threads.

And then there are the other, occasional visitors – birds bathing, mammals drinking, snakes hunting.

Rebuilding the pond

The pond water levels rises with rain and falls through evaporation. During the drought of 2019, the levels were particularly low. But it has never been completely dry, even after the fire.

This week we completely rebuilt the pond. The fire burned away the rubber liner down to the water level and filled the remaining water with ash and burned leaves. Now, three months post fire, we have replaced the liner and restored the pond to near new. So now we can watch the colonisation process all over again.

References cited

Seymour, R.S. & Bradford, D.F. 1987. Gas exchange through the jelly capsule of the terrestrial eggs of the frog, Pseudophryne bibroni. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 157: 477–481

White, A.W. 2017. Ecological and behavioural observations on populations of the toadlets Pseudophryne coriacea and Pseudophryne bibronii on the Central Coast of New South Wales, in Herpetology in Australia. Daniel Lunney and Danielle Ayers (Eds.), Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales.

Woodruff, D.S. 1977. Male postulating brooding behaviour in three Australian Pseudophryne (Anura: Leptodactylidae). Herpetologica, 33; 296-303.