Bembix (Bembicini)

Workbook

Bembix is one of the largest of the crabronid genera, worldwide. The genus is represented on all continents (bar Antarctica) and Australia is particularly species rich. There are currently 84 Australian species listed on AFD: as large as 24mm, as small as 8mm; brightly patterned in yellow or white, a mixture, or sometimes almost entirely black.

Bembix are also among the most familiar – and photographed - of the crabronids. Yet despite the large number of images online, rarely are these identified to species level. I hope to be able to put names to at least some of them. Soon.

Evans & Matthews (1973) provide a way forward

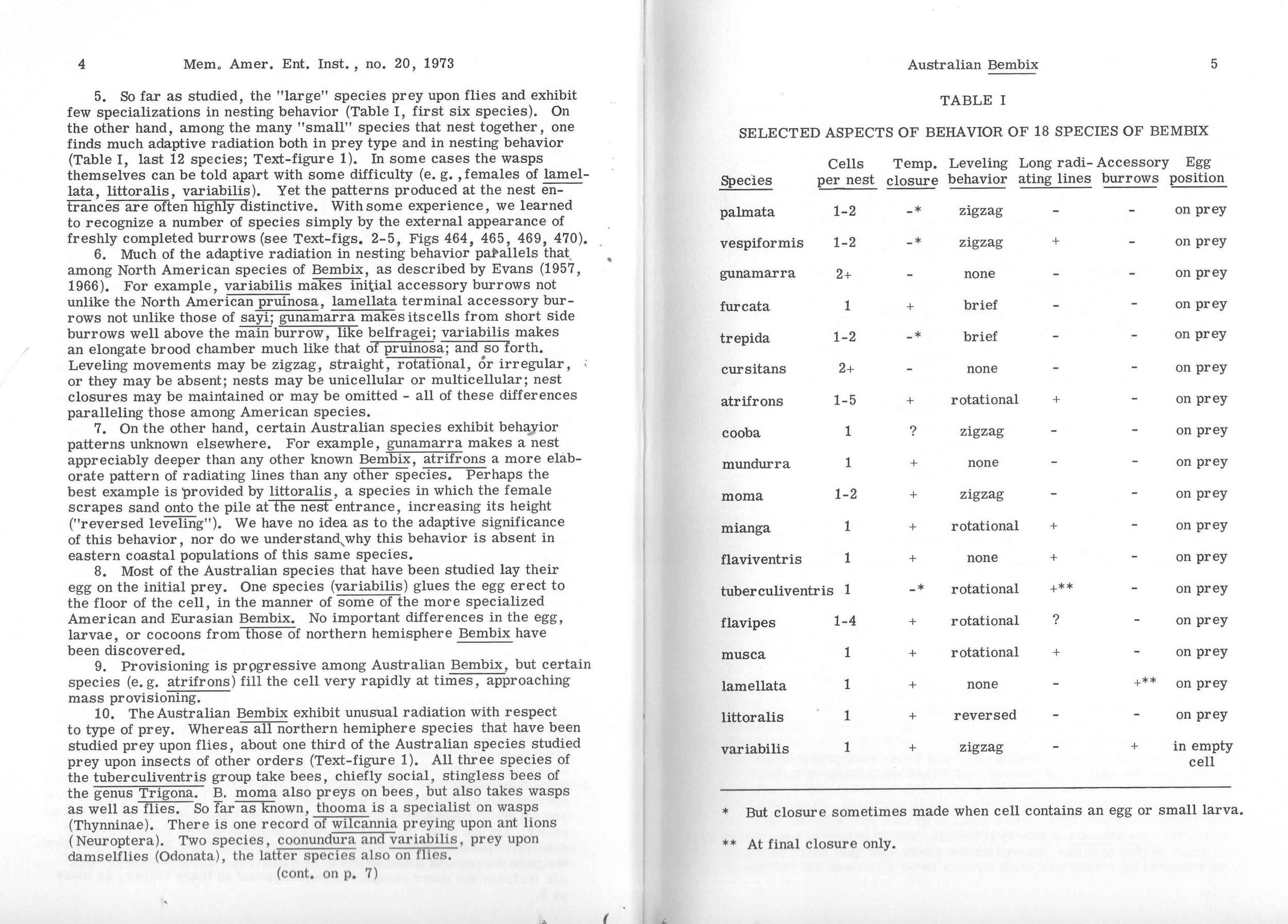

Thanks largely to the extraordinary efforts of Howard E. Evans and Robert W. Matthews, the taxonomic and biological diversity of Australian Bembix is well documented. Of particular importance is their 1973 publication Systematics and Nesting Behavior of Australian Bembix Sand Wasps. However, to the best of my knowledge, this impressive monograph is not available online. I feel very fortunate to have been gifted a copy of the book (all 387 printed pages) by one of the authors, Robert W. Matthews. This book includes the original description of 55 species, and reviews all those previously described. Since that time, a further four species have been added … again, thanks to the work of Howard E. Evans (1982, 1990).

Although the authors stress that their 1973 book is “far from being a definitive monograph of the Australian Bembix” (p. 1), it is an absolute gem. It is the culmination of twelve months of fieldwork (1969, 1970 & 1972), travelling throughout Australia, collecting and studying the nesting behaviour of sand wasps. Importantly, the authors also made an exhaustive study of material held in collections:

“This led us to study the Bembix in all major museums known to contain Australian material and to study the types of all species described from that continent (except two which are evidently lost).” (p.1).

As part of my own, modest crabronid project, I have recently turned my attention to Bembix. With ‘the good book’ in one hand and iNaturalist images in the other, I am seeking a way to put species names to faces.

Is it possible to confidently recognise individual species from field photos? If so, which species? And what features are diagnostically most useful?

There are currently nearly 1600 sightings of Australian Bembix on iNaturalist, and just a few of these have reliable species level identifications. Can I improve on this? Only time will tell – but I am optimistic.

Morphology

Australian Bembix can be distinguished from other members of the subfamily by the following shared characters: labrum exserted and at least as long as broad (in some cases, the length is twice the width); eyes essentially parallel; vertex sharply depressed alongside the eyes; ocelli greatly reduced, virtually absent. In addition, the gaster is sessile, with T1 nearly as broad as T2.

In distinguishing between species, useful characters include: labrum shape & colour; clypeus shape & colour; frons width and markings; front basitarsus shape and spination; male sternite shape; colour and dorsal patterning of the mesosoma and metasoma. For further details, see pages 9 to 11 of the Evans & Matthews (1973), below.

The images below illustrate many of these structural features and colour patterns, as discernible in field photos.

Males in some species have distinctive midline processes on the second sternite (S2) (star) and often also on the sixth (S6) (solid arrow). In Bembix furcata, these processes are quite diagnostic. Although this would seem to makes species ID trivial for male B. furcata, there are two complications. First, these processes can be greatly reduced in some individuals, and S2 not apparently bifid, particularly in small males. Second, to see these processes (or the sternites at all), requires a nearly lateral or (ideally) ventral view. Most photos are taken from above.

The lateral view of the clypeus in this male matches the description for Bembix furcata: strongly protruberant, evenly arched in profile (dotted arrow).

Bembix furcata

In Bembix furcata males, S2 is strongly projecting (star) and often apically cleft to form two points (‘bifid’); S6 has a broad and complex projection (arrows), including a pair of angles at the outer sides and a short, blunt apicomedial point.

Male and female Bembix are best distinguished on the basis of the number of metasomal segments visible dorsally. That is, a count of the tergites. Males have 7, females just 6. Antennae also differ in the number of flagellar segments (males with 11, females with 10). However, apical segments are often short and may be difficult to count accurately in many field photos.

Bembix furcata

In this male the clypeus (dotted pink arrow) is protruding and largely white, although black laterally and apically; the labrum (solid green arrow) largely black, but white-cream laterally. The mandible is pale in colour, the base just visible tucked in behind the labrum.

Note also the large, arched process on S2 (star).

Bembix furcata

In this species the vertex (star) is well below the level of the eye tops (line). The front basitarsus (arrow) is slender, narrowly margined black along the outer edge, and bears 6 slender, pale amber pecten spines. Note too that the following three tarsal segments are quite slender (not expanded or modified).

Bembix furcata

In this species, flagellomere 5 (F5) is slightly excavated beneath, F6 more strongly so, and F7 spinose beneath (arrow). Compare to Fig. 134 (Evans & Matthews, 1973).

Bembix furcata

In this female, the clypeus (arrow) is very strongly protuberant and prominent laterally. It is bright yellow but with a large, black spot mediobasally.

Bembix furcata

Note the small lateral yellow streak on the mesoscutum, just above the tegula (star). The scape (arrow) is black above, yellow below.

The clypeus in this female is wholly yellow, without the black basal mark seen in some other individuals of the same species.

Bembix furcata

A full frontal view is necessary to assess the level of the vertex summit (star) with respect to the eye tops. Here the vertex is well below eye level.

Species vary in the width of the frons (double-headed arrow) relative to the eye height. In this female the frons is broad, the inner eye margins nearly parallel.

Differences in mandible shape between species are subtle, but do provide useful information. Here the mandible has a strong cutting edge (dotted arrow), described by Evans & Matthews as “an oblique cutting edge between the apex and the tooth on the inner margin.”

The number of antennal segments differs between the sexes. Females have just 10 flagellar segments, while males have 11.

Bembix furcata

Of particular importance is the structure and colour of the front basitarsus (arrow), including the number of ‘pecten’ spines. In all Bembix species, tarsal segments 2-4 bear two pecten spines each but the number on the front basitarsus varies from 6 to 42.

Here there are 6 pecten spines on the front basitarsus, which is quite slender. Also of note is the darkened, slightly lobed outer edge.

The spur on the inner apex of the front tibia (green star) is distinctive in some species. Here it is unmodified, ‘simple’.

From this angle, the midline of the clypeus is visibly elevated (red star). The shape of the clypeus is a useful feature for distinguishing between species, although it can be difficult to discern in field photos.

Bembix furcata

An anterior view of the front legs displays the colour and number of pecten spines, and the shape of the basitarsus itself (arrows). In this female the basitarsus is long and slender (not broadly expanded), mostly yellow but with a darkened outer edge, weakly lobed at the base of the spines. The six spines are long, and amber in colour.

The clypeus in this female is elevated mediobasally (star).

Bembix furcata

While colour patterning typically shows at least some variation within a species, it still provides a useful piece to the ID puzzle.

Two of the thoracic regions of note are the pronotum and the mesopleura. Note that in Bembix, the pronotum is much lower than the mesoscutum. It is often largely concealed in dorsal view, so lateral shots are helpful.

Note too the large pronotal lobe (star), which is extensively yellow in this species.

This angle also demonstrates why the labrum (arrow) can be difficult to see – it is often tucked away under the head.

When digging, females will usually have the mandibles open and forward of the labrum, making their colour easy to determine. In this female they meet the description of ‘yellow’, as the dark apex is universal in Bembix and so is not mentioned in the summary table of species descriptions.

Bembix furcata

Many Bembix species are extensively, densely hairy (‘setose’). And these hairs readily trap sand and dirt, making it very difficult to see the colour pattern of the underlying structure. Just another of the challenges of species identification from field photos!

The six metasomal tergites confirm this as a female. Note how each tergite (the dorsal plate of the segment) extends laterally. The sternites (the equivalent ventral plates) are not visible from this angle.

Bembix furcata

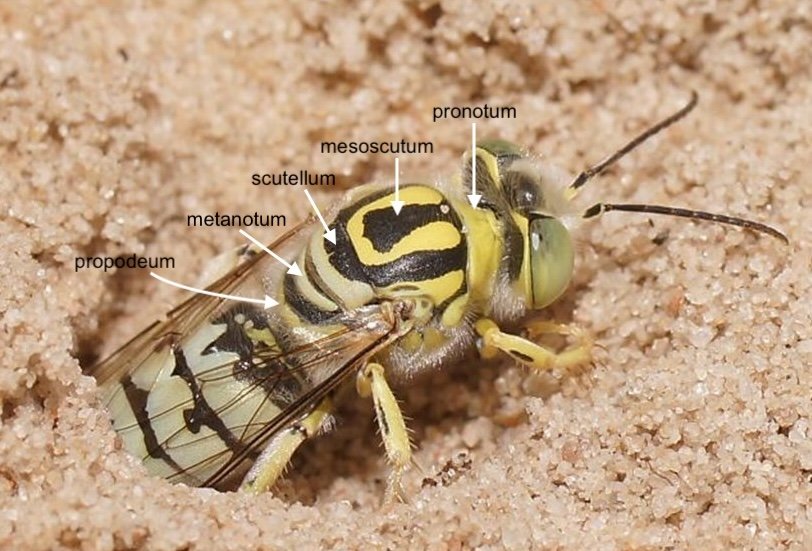

The major visible plates along the dorsal midline of the mesosoma are: pronotal collar (low in Bembix, relative to the mesoscutum); mesoscutum (often simply called the scutum); scutellum; metanotum (very short); and the propodeum. When the wings are in the usual position at rest, the propodeum is obscured, as it is in species with particularly dense setae (hairs).

The U-shaped yellow mark on the mesoscutum is referred to as a discal mark. In some individuals (and species), the discal marks are much narrower than this, and the segments of the U are often not connected.

Bembix variabilis

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/25727992

The features shown in this image are diagnostic for Bembix palmata males. The bright yellow clypeus is concave apically, has prominent round lobes laterally (curved solid arrow), and has a small median, basal ridge (star). The labrum is depressed near the base (dotted arrow), and also bright yellow. And the shape of the extremely broad front basitarsus (straight arrow) is unique.

Bembix palmata

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/147447501

The best chance to see the sternal process of males is when they are feeding at flowers. This species has a high ridge on S2, right-angled at the apex (straight arrow).

The yellow marks on the sides of the propodeum (curved arrow) are also visible from this angle. Note too the yellow marks on the extreme lateral sides of T1, highlighting the extent to which the dorsal tergites wrap around ventrally.

Bembix palmata

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/147447501

The uniquely shaped front basitarsus (straight arrow) of Bembix palmata is worth showing again. Note too the broadly expanded lobes of front tarsomeres 2, 3 and 4 (stars).

The shape of the male antenna is another feature that can helpful in species recognition. Modifications tend to start at flagellomere 5 (curved arrow), and in this species it is strongly spinose. Compare to Fig. 121 (Evans & Matthews, 1973).

Bembix palmata

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/105595939

Although the diagnostic features in females of this species are not as pronounced as in the male, they are nevertheless enough for a species ID (when taken in combination with colour patterning).

As in the male:the clypeus is broad with a median carina basally (star); the labrum is depressed basally (dotted arrow); and the front basitarsi are expanded (solid arrows) as are the following tarsomeres.

Note too the vertex level with the eye tops (line). This is the not an uncommon condition, but it does contrast with some other extensively yellow species such as B. flavifrons.

Finally, in this species the female typically has a pair of black spots on the yellow clypeus. This too is a widespread pattern, seen in many species (yet often highly variable within a species).

Bembix palmata

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/66902356

The five species of the Pectinipes species group are characterised by their numerous pecten spines. All have at least 10, and some as many as 42! This female has 12 I can count, and probably more. Compare to Fig. 36 (Evans & Matthews, 1973).

Bembix flavifrons

Image courtesy Reiner Richter

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/150716071

The large number of pecten spines immediately identifies this as one of just three species (the Pectinipes species group). The highly distinctive shapes of the clypeus and labrum shape are diagnostic, and the strongly curved antennae provide further support.

Bembix flavifrons

Photographer: Mark Norman (Museums Victoria)

https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/specimens/2482511

Accessed 21 December 2025

There are few Australian Bembix that can be unambiguously identified to species level based on the colour pattern alone … but this one can! Commonly referred to as the ‘Panda Sand Wasp’, Bembix vespiformis is unmistakable. There is some variation … the apical segments are not always orange (particularly in the east), and T2-4 may be all black or have white spots. But the large, tapered white spots on T2 are a consistent feature.

Bembix vespiformis

Image courtesy Kerry Stuart

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/198711178

Despite the distinctive colour pattern, I like to check as many other features as possible against a putative species description. For example, here the colour of the mandibles, legs, mesoscutum all fit with Bembix vespiformis … as do the 7 long, dark pecten spines on each of the front basitarsi (arrows).

Note that this is one of many Bembix species widely distributed across continental Australia.

Bembix vespiformis

Image courtesy Kerry Stuart

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/195650631

The differences in mandible shape between species are slight and somewhat relative … yet they are important. In some cases, they are one of the few reliable diagnostic characters. For example, female B. littoralis and B. variabilis are structurally very similar. Colour patterns certainly help but as both are highly (highly!) variable species, a structural feature provides a valuable cross-check. Both species have slender mandibles, but that of B. variabilis is particular slender and straight, with a very small tooth (green arrow).

Mandible shape correlates with nest substrate. Species that nest in coarse sand or compact soil typically tend to have robust mandibles, strongly curved, and with an oblique cutting edge between the apex and the tooth. In contrast, those that burrow in very friable substrate tend to have slender mandibles with little or even no cutting edge … as in this B. variabilis.

B. variabilis

Image courtesy Faz

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/335029293

Bembix of Eastern Australia

A first step

Half of Australia’s described Bembix species have been collected in the eastern part of Australia, and it is these that I am concentrating on in the first instance. This makes the task more manageable. It is also where the majority of iNaturalist sightings were made (83%, at last count). In addition, it is where I live and spend most of my time – so that lends its own bias to my decision. I do plan to cast an eye further west eventually. But one step at a time.

So for now, the table below contains only species known to occur in QLD, NSW, ACT, Victoria, Tasmania, or south eastern SA. Not included are species known only from WA, NT or SA outside the south east.

Summary table, with emphasis on the more common species

The following summary table for eastern species is large and detailed. Necessarily so. With 44 known species, and so much recognised variation within species, a more simplified cheat sheet would not really work. In nearly every case, a range of structural and colour features will need to be considered in combination, and the options available will always be constrained by what details are visible in any given set of photos.

Perhaps over time I will delete some of the columns, but for now I’m being as thorough as possible.

Some of the more recognisable species

Some good news. It is indeed possible to confidently ID several Australian Bembix species from field photos, despite the large number of species and the intraspecific variation of many. Here are a few examples.

NOTE: this is the only species known from Tasmania

- clypeus white, bordered black; labrum black

- centre of vertex well below level of eye tops

Note: this is the only species known from Tasmania

- clypeus prominent laterally

- centre of vertex well below level of eye tops

- band on T1 has an angular median notch (in addition to the pair of more lateral emarginations)

- colour of metasomal bands is typically cream or off-white (but may be brighter yellow in some individuals)

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/25727992

(image courtesy Reiner Richter)

- discal markings on mesoscutum may be a pair of large yellow streaks and a transverse yellow mark behind (as here), or these may be thicker and connected to form a solid U-shape

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/107168910

(image courtesy Hauke Koch)

- tricoloured mandible

- large (broad?) S2 projection

- S6 elevated, angulate apically

- unusually dense & long pale hairs, including on T1 & propodeum

- metasoma mainly black, limited white markings

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/145146372

(image courtesy Brian Byrnes)

- central vertex above eye level

- clypeus & labrum wholly pale

- large yellow spot on mesopleura

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/145157864

(image courtesy Brian Byrnes)

- front basitarsus much expanded from base; broad & flat: following tarsomeres also expanded on the outer margin

- clypeus prominent laterally, forming round & projecting lobes

- bright yellow legs, clypeus, labrum

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/256325551

(image courtesy Graham & Maree Goods)

- metasoma with strongest white marks on T1, tapered medially; following tergites mostly black

- apical tergite may be orange

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/25832854

(image courtesy Teale Britstra)

- clypeus protuberant but flattened apically, & with oblique black markings basally

- front basitarsus slender, & with darkened lobes at base of each pecten spine

- T1 has yellow spot at extreme side, in addition to white marking more dorsally

- S1-5 with yellow lateral spots

https://inaturalist.ala.org.au/observations/203204274

(image courtesy Phil Warburton)

- numerous pecten spines on front basitarsus (at least 16)

- expanded front basitarsus

- clypeus shape diagnostic, with pair deep lateral grooves and strongly elevated medially and laterally

- labrum also unusual form, with median basal sulcus and strongly elevated laterally

- mid tibia much expanded from a slender base

Photographer: Mark Norman (Museums Victoria)

https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/specimens/2482511

Accessed 21 December 2025

This is one of the most common and widespread species … yet it remains an identification challenge. The variation in colour is “almost beyond description”, and they are rather generalist in their morphology. However, it can be done. With caution. This one I’m confident of, having obtained a specimen for a closer look. In particular, note:

- broad and high vertex, strongly elevated centrally

- slender mandibles

- in this dark variant, the combination of minimal mesoscutal markings with narrow metasomal bands (in contrast with coast B. variabilis, which have broad metasomal bands even when the mesoscutum is entirely black) more details here

Please note. The above identifications are simply my suggestions, based solely on comparing the images to the published descriptions. This is not intended as a definitive photo guide. The images are all linked to the source iNaturalist observations, and these should be checked for corrections and comments over time. As the iNaturalist community starts taking these wasps to species level, I’m sure we will all hone our identification skills.

Select species, in detail

As opportunities arise, I take a closer look at individual Bembix species.

A rather old specimen, collection details unknown … but my first chance to take a close look at this species.

Arguably one of the most variable Bembix species in terms of colour pattern … and therefore one of the most challenging to identify from field photos. Finally I have one in the hand and so can be more confident that this is indeed B. littoralis.

This page includes a detailed comparison matrix for five Bembix species which can sometimes look very alike: B. littoralis; B. variabilis; B. lamellata; B. musca; B. furcata.

Published in 2017, after my first serious encounter with nesting Bembix, this blog post was in need of a facelift. And worth it. In the years since, I’ve not encountered as much action as I did on that November day.

At the time I knew little. Not the identity of the wasps. Nor the basis for the behaviours I was seeing. With the benefit of hindsight, I reinterpret that early encounter with Bembix furcata . [January 2026]

The widespread fascination with sand wasps come from their behaviour. Large numbers of often colourful wasps, zipping noisily about a sandy track or dune. So here’s a glimpse of the biology of one of the common species in southern Australia, Bembix furcata.

Essential extracts

Diagrams in Evans & Matthews (1973) show various details referred to in the species descriptions, such as:

the front tarsi, including basitarsi and pecten spines (males & females; many species)

the mid tibia, including tibial spurs (males & females; many species)

male antennae (most species)

The relevant figures are referenced in my summary table (matrix), and copies of the figures are included below.

Also included are pages 3 to 8, presenting a summary of their major conclusions.

Evans and Matthews: dedicated students of comparative behaviour

“There are fragmentary reports that some of the southern hemisphere species have unusual prey preferences (Wheeler and Dow, 1933). Clearly it is time that students of comparative behavior turned their attention to the many species of this relatively well-studied genus occurring south of the equator. [] … We quickly found that no comparative behavioral studies were possible without first clarifying the systematics of the Australian Bembix. In fact, accurate identification of species proved almost impossible, and about a third of the species we studied in the field we found to be undescribed.” (Evans & Matthews, 1973 p.1)

As nesting behaviour of sand wasps was the real motivation behind their study, it seems only fitting that I include at least some of their ethological findings. I have added brief notes and examples to my summary table. The authors’ own Summary of Major Conclusions (pp 2-7, see above) includes several findings related to behaviour. In addition, below are pages dealing with the brood nest digging behaviour of both B. variabilis and B. littoralis. I feature these particular species for two reasons. First, they are two of the most abundant and widely distributed species of the genus. Second, females are very difficult to tell apart in the field: “We have found that it is often easier to tell these two species apart by the structure of the nests than by the structure and coloration of the adult females.” (Evans & Matthews, 1973. p 292).

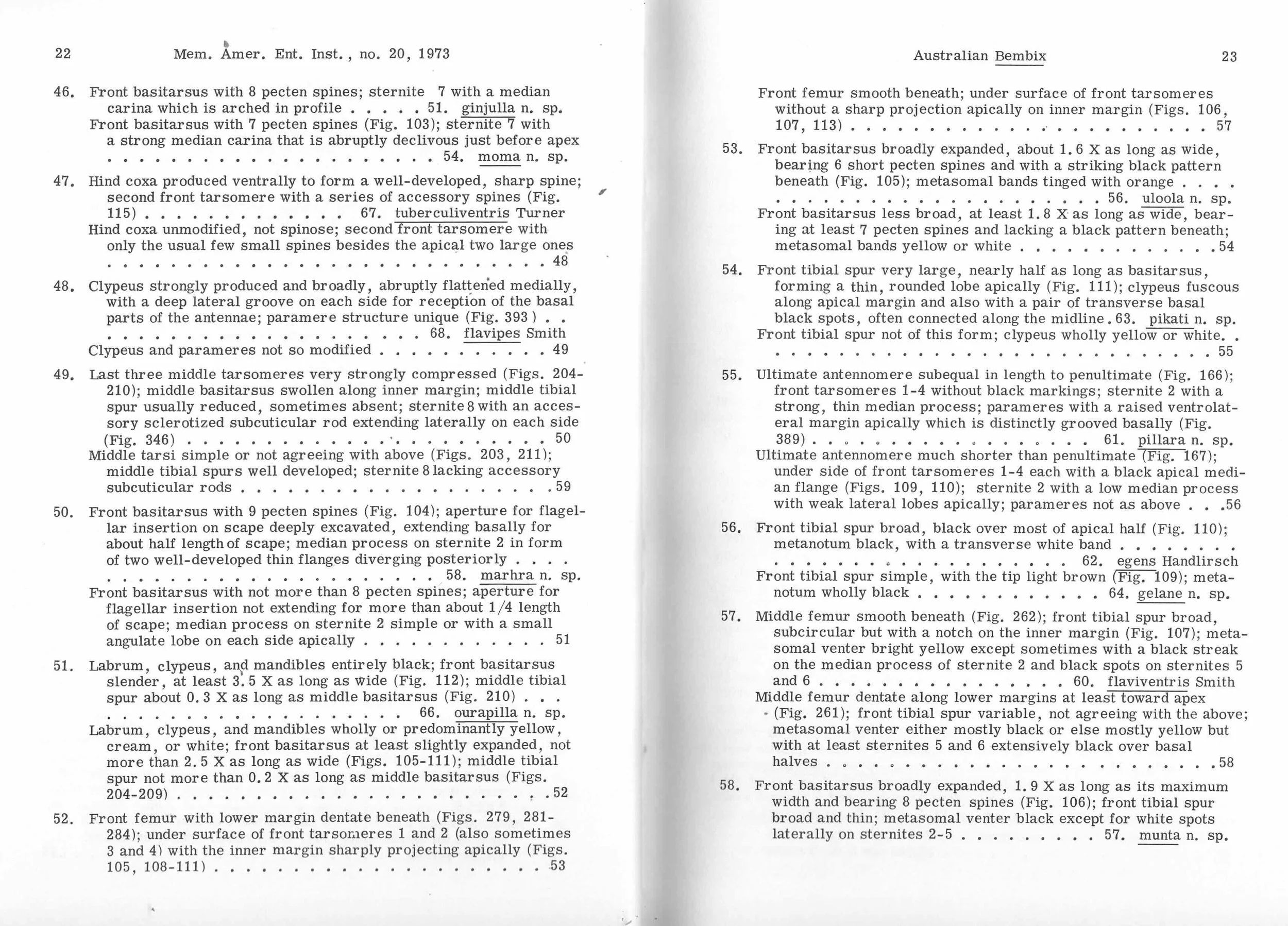

Key to Species

Of course, Evans & Matthews (1973) includes a key to all 80 species known at that time.

Other bits & pieces

Many species are represented in Australian museum collections, but few of these are as yet available as online images. Below are those I’ve found to date, including the holotype of Bembix wanna from Victoria. BOLD has 10 specimens listed, and the genetics suggest these represent at least six different species, but they are identified to genus only and with just a single, lateral image of each. I have included a couple here, simply to illustrate structural and colour diversity.

References

Evans, H.E., Evans, M.A. & Hook, A. 1982. Observations on the nests and prey of Australian Bembix sand wasps (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). Australian Journal of Zoology 30: 71-80

Evans, H.E. & Matthews, R.W. 1973. Systematics and Nesting Behavior of Australian Bembix Sand Wasps. Memoirs of the American Entomological Institute, Number 20.

Evans, H.E. & Matthews, R.W. 1975. The sand wasps of Australia. Scientific American, 233(6); pp 108-115

Evans, H.E. 1982. Two new species of Australian Bembix sand wasps, with notes on other species of the genus (Hymenoptera, Sphecidae). Australian Entomological Magazine 9: 7-12

Evans, H.E. 1990. New Australian species and records of the promontorii group of the genus Bembix F. (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae: Nyssoninae). Journal of the Australian Entomological Society 29: 27-30

Evans, H.E. & O’Neill, K.M. 2007. The Sand Wasps: Natural History and Behaviour. Harvard University Press

This is a workbook page … a part of our website where we record the observations and references used in making species identifications. The notes will not necessarily be complete. They are a record for our own use, but we are happy to share this information with others.