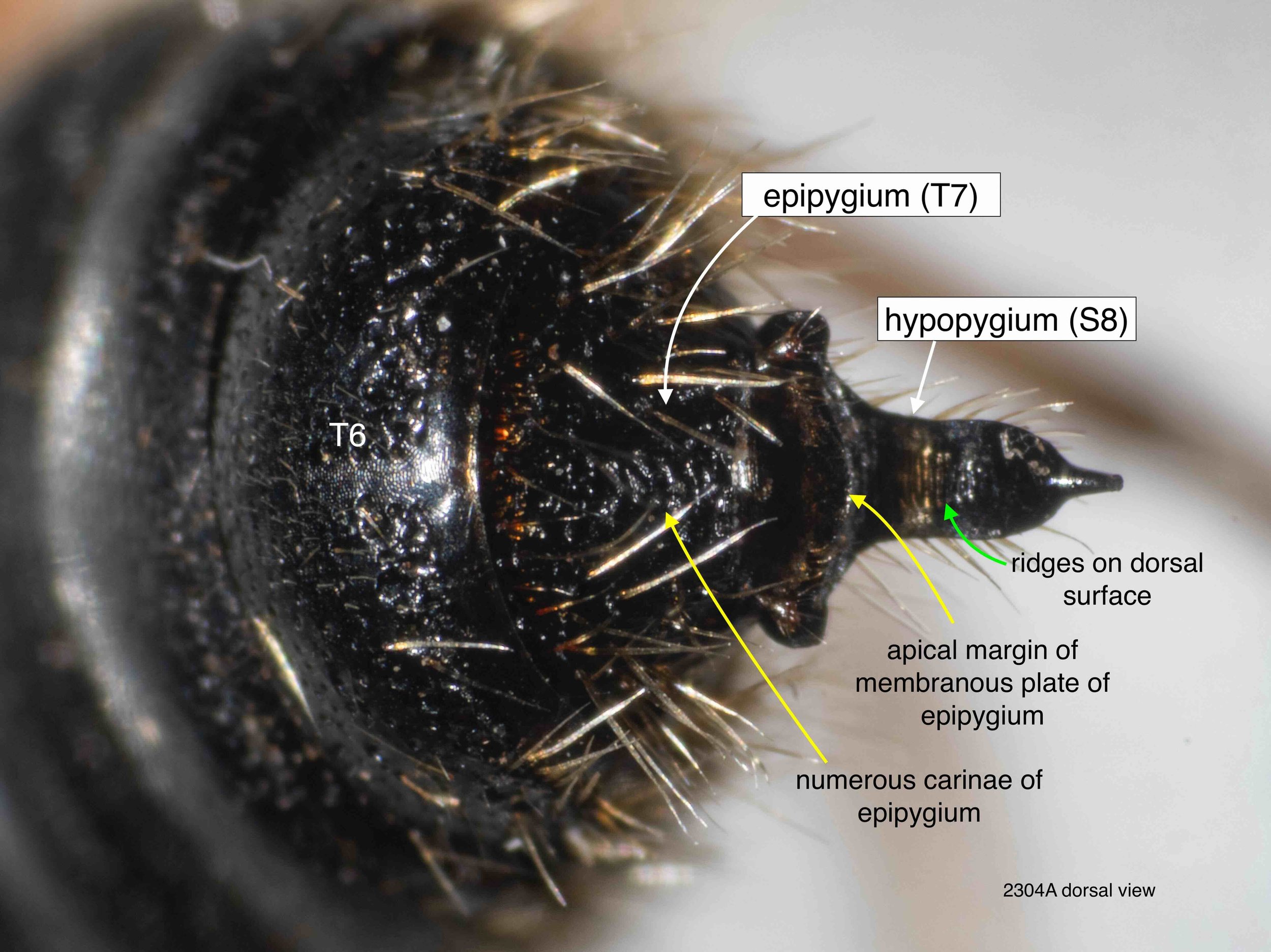

Thynninae - male genitalia 2304A

Workbook

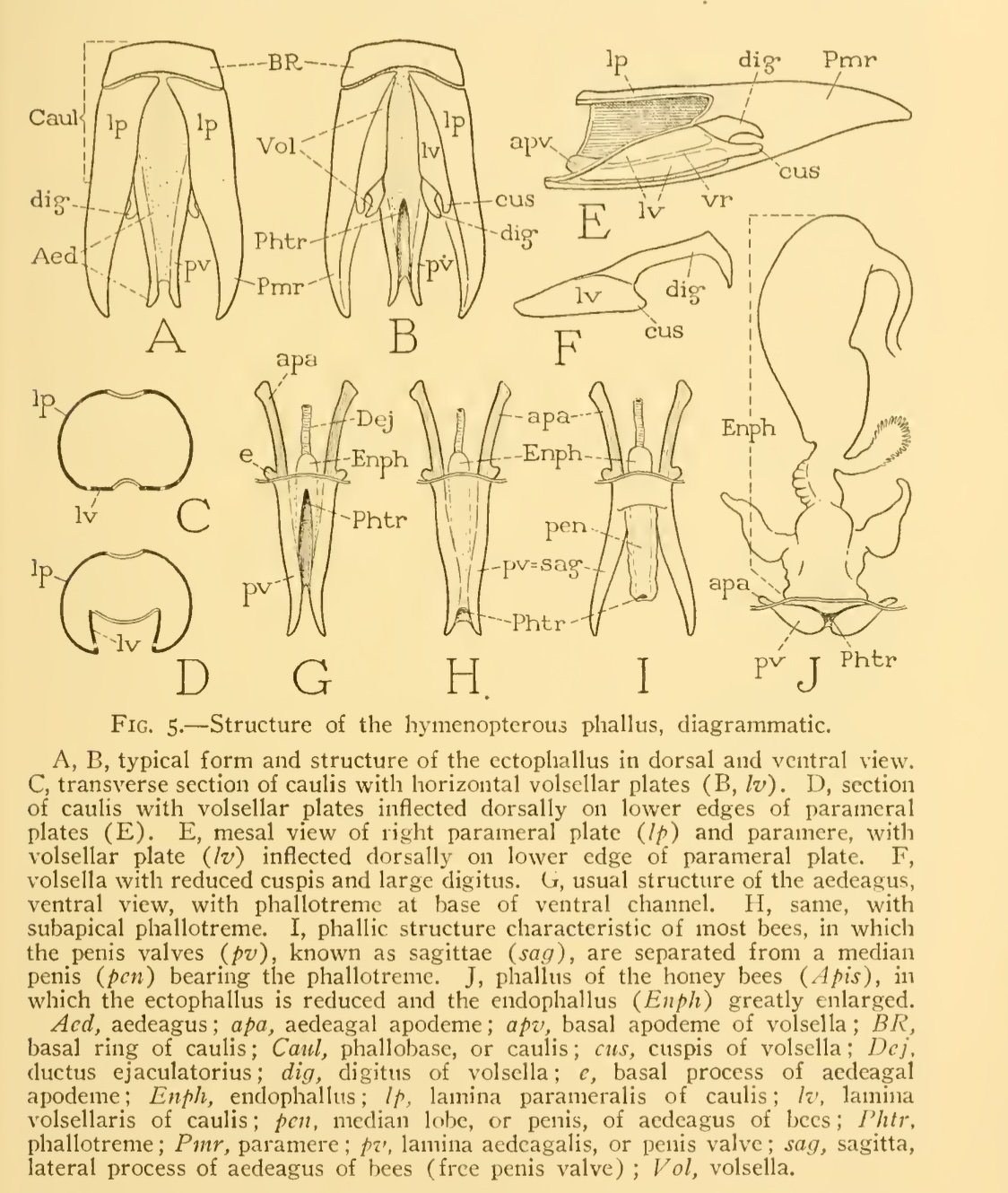

This is my first attempt at understanding the structure of male genitalia in this subfamily. Most species descriptions and keys for thynnine wasps refer to the shape of structures such as the hypopygium, epipygium, parameres, basiparameres and aedeagus. I hope to be able to see at least some of these in field photos, so I need a better understanding of what I’m looking at.

As it turns out, this should help me with hymenopteran anatomy more broadly …

“The general structure of the phallus is remarkably consistent throughout the order, and in a comparative study little difficulty is encountered in identifying corresponding parts. Special types of modification, however, are in many cases characteristic of superfamily groups, and details of structure undoubtedly will be found to be diagnostic of species among the Hymenoptera as in most other insect orders.” (Snodgrass, 1941. p. 12)

In addtion, these notes were compiled in preparation for blog post titled ‘Flower wasp coupling’ (published March, 2024).

I took advantage of a rather large specimen collected last year. This male was found dead, hanging in bushes (April 5, 2023), and stored dry for future study (specimen # 2304A).

Before dissection

Intact dry specimen, imaged 5 Feb 2024.

Dissection

Step-wise removal of genitalia from chamber at the end of the abdomen. A gentle squeeze with scisssors was enough to separate the terminal segments from the rest of the body. The following steps simply involved lifting away successive sclerites.

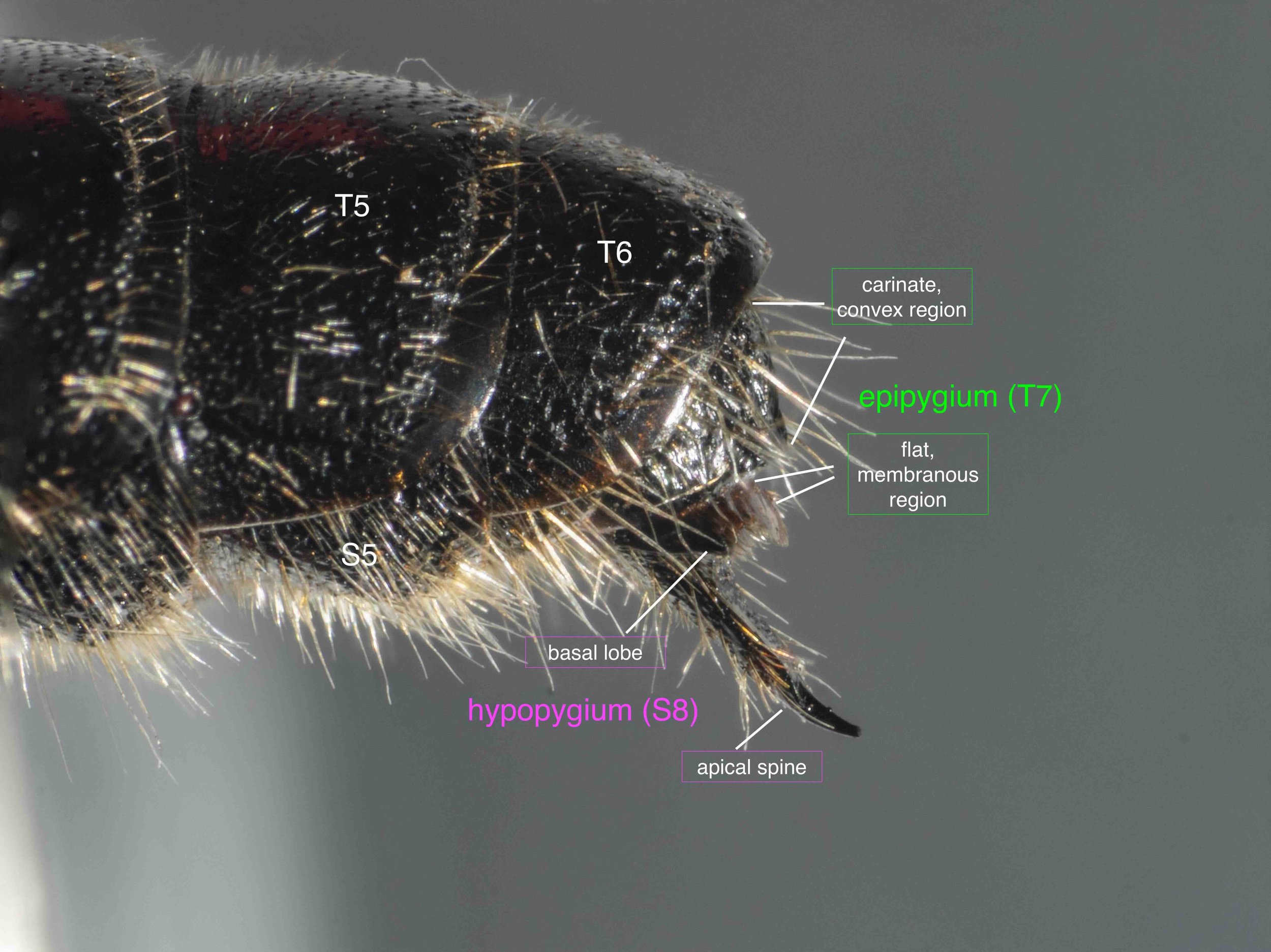

Hypopygium (S8)

S8 forms the hypopygium, the sclerite that encloses the genital cavity ventrally. In this and many other Thynninae, the apical section extends well beyond the tip of T7 and is clearly visible in the living/intact wasp. S8 fits closely inside S7 such that the pair seem to be almost a functional unit. After separation of the S8 from S7 (Step 4), I imaged S8 (images 4-6 below) and then soaked it in NaOH overnight to remove dried muscle and other tissues before imaging again (images 7-10 below).

Epipygium (T7)

T7 forms the epipygium, the sclerite that encloses the genital cavity dorsally. It is less heavily sclerotised than the hypopygium and tends to curl inwards laterally such that in situ it grips the more ventral elements, and once removed it almost rolls into a tube. Once isolated, the epygium was soaked in NaOH overnight before imaging (images 3-4 below).

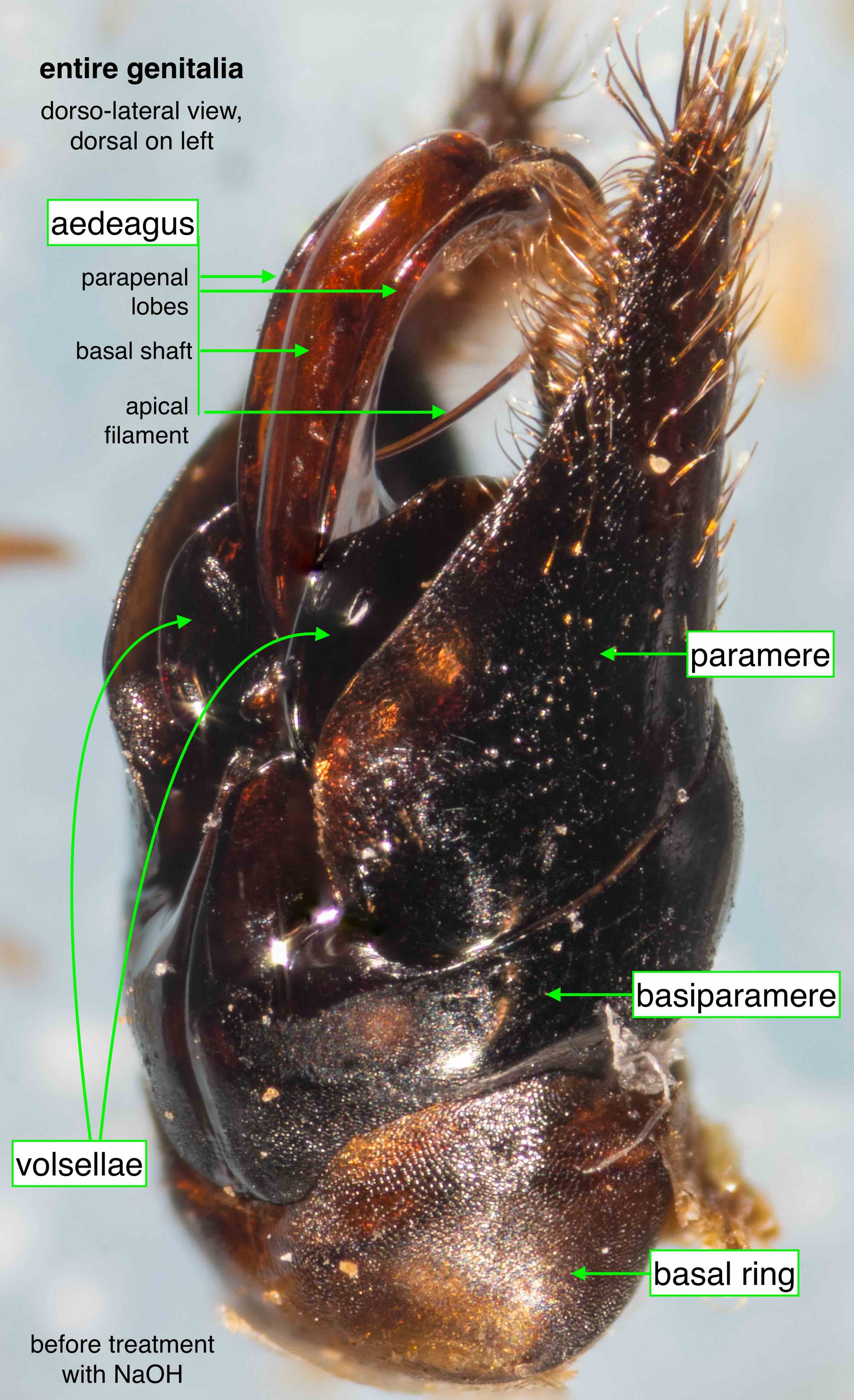

Genitalia: entire

After Step 5, the genitalia (‘phallus’) was free of the other abdominal structures. Step 7 involved treatment in NaOH to remove dried tissue. I also teased the pair of parapenal lobes away from the tip of the aedeagus and, eventually, lifted the apical filament into the open.

I have included similar images before and after treatment in NaOH. In keeping with the convention typically used by Graham Brown, the genitalia are shown with the apex to the top where appropriate

Genitalia: the individual components

volsellae

Each volsella is a single sclerite with an elaborate, three-dimensional shape. I have not attempted to identify the ‘cuspis’ and ‘digitus’ described by Snodgrass etc, but rather applied common names (and coloured arrows) to the equivalent structures in the range of views below.

The most notable components of the volsellae are the apical spines and deep, dorsal grooves.

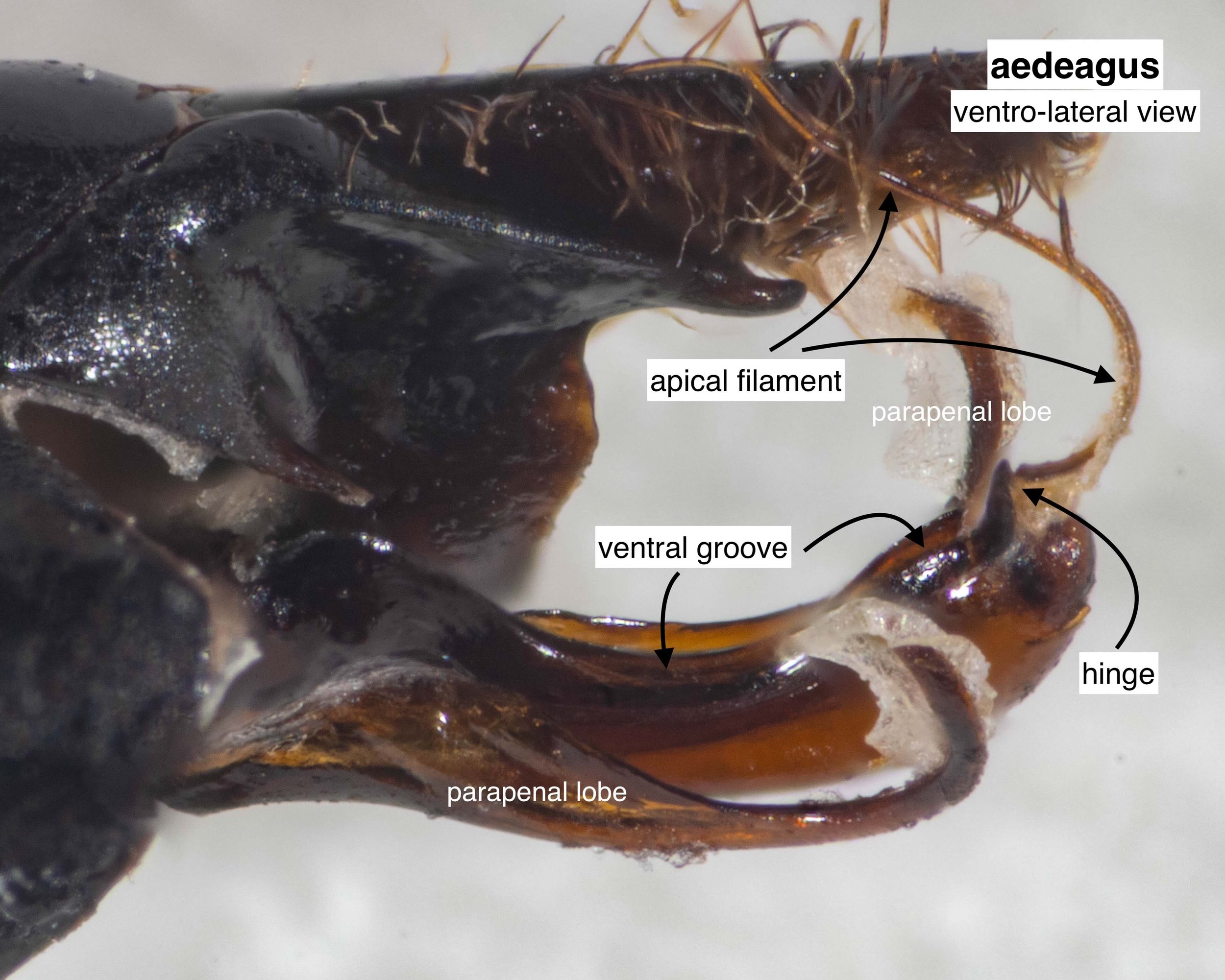

aedeagus

The lateral structures I have labelled as parapenal lobes may or may not correspond to the parapenal lobes as described by Brown. Similarly, with my use of the term ‘hood’ … although it seems an apt description for the strongly rounded end of the main shaft.

During dissection, I teased away the ends of the parapenal lobes away from the apex of the aedeagus in order to view the various structures. It is unclear to me whether these are normally free or attached by a thin membrane.

Notable components of the aedeagus include the long ventral groove, curved dorsal hood, and the moderately long apical filament/loop.

basal ring & basiparameres

The basal ring of hymenoptera is an annular sclerite to which the extrinsic muscles attach (Snodgrass, 1941). It also bears muscles which attach to the basiparameres. It is therefore unsurprising to find it a strong structure with an extensive apodemal plate.

The basiparameres in this species are clearly separated from the parameres, the latter being readily removed.. The left and right basiparameres are fused both dorsally and ventrally.

paramere

Each paramere is partly ‘hollow’. A basal opening (marked ‘pocket’, in the images below) leads into a lumen which runs to the apex in the ventral half of the paramere. It’s likely that muscles normally extend into the paramere from the basiparamere.

The dorsal region appears solid, without an obvious cavity.

References

Brown, G.R. 2000. Some problems with Australian Tiphiid wasps, with special reference to coupling mechanisms. Hymenoptera: Evolution, Biodiversity and Biological Control (ed. Austin, A. & Dowton, M). CSIRO Publishing.

Snodgrass, R. E. 1941. The male genitalia of Hymenoptera. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 99(14), 1-86 + plates.

This is a workbook page … a part of our website where we record the observations and references used in making species identifications. The notes will not necessarily be complete. They are a record for our own use, but we are happy to share this information with others.