Cocoon A contents

A reminder of the scene that greeted me when I first tore open the cocoon within cell A.

shorter wings, small eyes

Many of the females I saw when I first opened the cells looked like this. Her wings are short and her eyes less prominent than in ‘later’ females. I’m assuming this is a ‘brachypterous female’ … although the differences aren’t as obvious I imagined they might be.

early stage female pupa

Even at this early stage of transformation, this is clearly female – the scape is not swollen (white arrow). And it is evidently a long-winged (dispersive) female – the eyes are large and bulging (green arrow) and the wings are relatively long (F = tip of forewing; H = tip of hindwing).

male pupa

Sexes are easily distinguished, even at the pupal stage. Most obvious are the swollen bases (‘scapes’) of the antennae in the males (white arrows).

late stage male pupa

This is the same male pupa as in the previous image, but one day on. The cuticle is darker, the body bristles longer, and the wing more developed (white arrow). He emerged the following day. Note that even at this stage there is no obvious eye … yet another clue as to sex. In females the bulging eyes are apparent early in pupal development.

fully winged

Her wings extend to nearly the end of her abdomen, and her eyes are well developed. Most females have this form. Her oldest sisters, however, were short-winged and would never seek to leave the nest.

virgin female

She regularly visits male pupae, touching them with her antennae. I had removed all the adult males from this dish before she emerged from her pupa. Now she must wait. Only once mated will she seek to leave her natal nest.

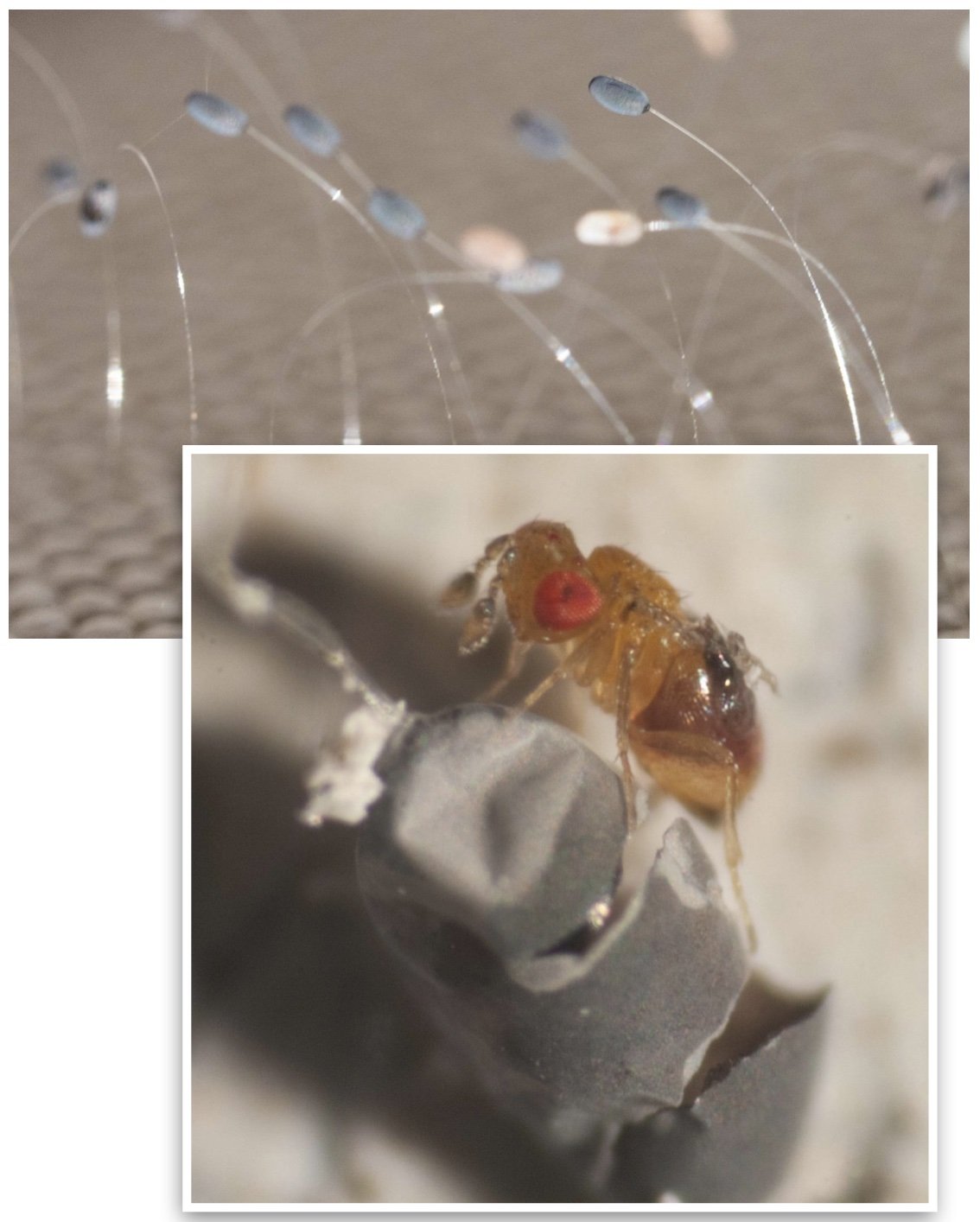

newly emerged male

The bulging antennae, short wings, and pale colouration of males are on show in this newly-emerged male. This is the same individual as in the preceding pupal photos. He doesn’t feed, and over the coming 7-8 days of his life his abdomen will shrink as his body depletes its internal reserves.

male antennae

The rather extraordinary structure of the male’s antennal scapes are consistent with drawings of M. australica and quite different to those of most other Melittobia species (Dahms 1984a). I think there can be little doubt about the species ID – particularly as this is the only Melittobia known from Australia.

[ventral view of male]

leaving home?

These sisters seem keen to depart the nest. They walk toward light, are relatively fast moving and responsive to movement … all the behaviours I’d expect to see in mated females of the long-winged form. They regularly communicate with one another using their antennae.

female features

A long-winged female, with large protruding eyes. Note the antennal scapes are not swollen (in contrast to males).

a posturing male

When I first opened Cell A it contained 7 males. They were clustered in a space at the end of the cocoon … along with several females. He appeared to be posturing – standing tall, wings elevated, antennae erect.

courtship is a rough affair

It looks like an attack. The male is tightly clutching the female’s head with his mandibles and she seems quite passive.

prolonged & persistent

The couple seem rather immune to disturbance during courtship. I used a paintbrush to lift the pair out into the open for a better photo … and they remained together.

receptive or not?

He grips her antennae with his and strokes her body with his legs. The antennal contact probably also involved chemical cues, as he has surface glands on the enlarged scapes. At this stage it is not possible to say if she will be receptive – she doesn’t give consent until the end of the courtship ritual (Dahms 1984b). Females typically mate just once.

sharp teeth!

The mandibles (jaws) of males are larger than females, and each is tipped by a sickle-like tooth (arrows). This equipment is not for eating (males don’t eat). They can employ these as weapons in combat with rival males, and may fight to the death.

[ventral view of male]

Cocoon B

As it appeared before I tore away the papery cocoon to reveal the contents.

clumps of eggs and tiny larvae

The larva from cocoon B was still relatively undamaged … and no doubt alive. It was motionless. At this prepupal stage, they are largely immobile anyway, but the addition of toxins from the founding parasitoid would have effectively paralysed the host. This ensures that her eggs and larvae are not dislodged or crushed.

feeding larvae

The hatched larvae, with their segmented bodies, are already feeding. Some are larger than others, their guts appearing yellow through otherwise transparent bodies.

rapidly growing larvae

When I first opened Cell B (on 7th May) the larvae were small and not obvious. Two days later it’s a different story!

a seething mass

Note that on 7th May I removed all adults from this enclosure. The plan is to monitor these through to maturity. This will give me an estimate of life cycle timing and sex ratios. I expect only around 5 males for every 100 females. The genus has a well documented female bias.

ectoparasites

The larvae remain outside the body of the host as they feed. They have relatively small mouthparts and are quite maggot-like in appearance. All they need do for the next week or two is feed and grow. By the time they are ready to pupate they will be 1.6mm in length … roughly the same size as the adult wasp they will become.

female seeking a host

Solitary endoparasite of moth pupae, including ghost moths (Hepialidae) in the soil.

Lissopimpla excelsa

female seeking a host

Solitary kleptoparasite of the larvae of solitary bees & wasps. They develop inside the nest, where they consume both the host and its provisions.

Gasteruption terminale

female seeking a host

Solitary ectoparasite of wood-boring longhorn beetle larvae.

Callibracon

female laying eggs beneath leaves

Endoparasite of the larvae of sawflies, caterpillar parasites, or vespids. Her eggs are first eaten by foraging larvae (sawflies or caterpillars). They may develop directly (inside the sawfly), attack parasites already inside the caterpillar, or if the caterpillar captured by a vespid wasp and fed to its own larvae, then the trigonalid will strike. It’s a complex, convoluted tale that I plan to explore in a later blog post.

Taeniogonalos (tbc)

investigating a log, probably seeking a host

Solitary kleptoparasite of various wasps, including crabronids. The ‘cuckoo wasp’ consumes the egg or young larva and then the food cache before pupating in the safety of the stolen nest space.

Primeuchroeus

female checking a crabronid burrow

Solitary ectoparasite of mature wasp or bee larvae. This female ‘velvet ant’ was investigating a crabronid burrow (Cerceris).

small and we don't see them often

Solitary endoparasite of lepidopteran pupae.

Antrocephalus (tbc)

tiny male, resting before rejoining the swarm

Endo or ectoparasitic on ant larvae or pupae. Until I have a better ID, I’m extrapolating from general information on the putative family. Seen in mid January. I collected one, for later study. Length: 3mm + antennae.

another day, another swarm ... but different wasps

Similar in appearance and behaviour to the little black ‘chalcid’ seen in mid Jan, but clearly not the same. Simple antennae, stout petiole, golden body … another puzzle.

they would land just long enough for me to get a shot or two

Endo or ectoparasitic on ant larvae or pupae. Until I have a better ID, I’m extrapolating from general information on the putative family. Again, I collected a few … for later. Length: 2.5mm + antennae.

from inside a butterfly egg

Two butterfly eggs developing atop a leaf each gave rise to a single, tiny wasp.

Telenomus. Length: 0.75mm.

[host – Heteronympha merope: NYMPHALIDAE]

[full details in Pauls’ 2018 blog ‘Reproduction - Russian doll style]

from inside a lacewing egg

Some lacewings lay their eggs on slender stalks. These normally give rise to hairy little nymphs that are voracious predators of psyllids. But from each of these darkened eggs, a single tiny wasp emerged.

Trichogramma. Length: less than 0.5mm (females slightly larger).

[host – Neuroptera, species uncertain]

[full details in Paul’s 2018 blogs ‘Déjà vu! Another egg parasitoid wasp’]

from inside a free-living caterpillar

Remember the little wasps we discovered as they emerged from a caterpillar? That single caterpillar was host to around 30 endoparasites. When it eventually died, the wasp larvae broke out to spin silken cocoons across its back.

Cotesia wonboynensis. Length: over 3mm

[host – Anthela: ANTHELIDAE]

[full details in Paul’s 2019 blog ‘Rearing wasps … by accident’]

from inside a sheltered psyllid nymph

A solitary endoparasite, these wasps have two layers of protection as they develop: the body of the nymph, and the thin, sugary cap that it lives beneath - the ‘lerp’.

Psyllaephagus.

[host - Hyalinaspis: APHALARIDAE, an hemipteran]

[full details in Paul’s 2018 blog ‘Life on a leaf’]

from inside the pupal cocoon of a crabronid wasp

Each of the three cells of this Pison nest had yielded an identical female mutillid, or ‘velvet ant’. A solitary ectoparasite of an enclosed, mature larva or prepupa. The cocoon was spun by the host.

Aglaotilla.

[host – Pison: CRABRONIDAE]

[for the full story see my 2021 blog ‘A window into mud-nests’]

from inside the mud cell of a sphecid wasp

Five out of 19 cells in a massive mud-dauber nest gave rise to cuckoo wasps. The nest was collected on the north coast of NSW … neither the host nor parasite is a species we know here, although both are reportedly widespread across Australia. Cuckoo wasps are solitary kleptoparasites … they consume the young host and then the food cache. In this case, the paralysed spiders. The parasite then spins its own cocoon within the protective cell of the mud nest.

Chrysis lincea.

[host – Sceliphron laetum: SPHECIDAE]

[for the full story see my 2022 blog ‘Wasp forensics’]

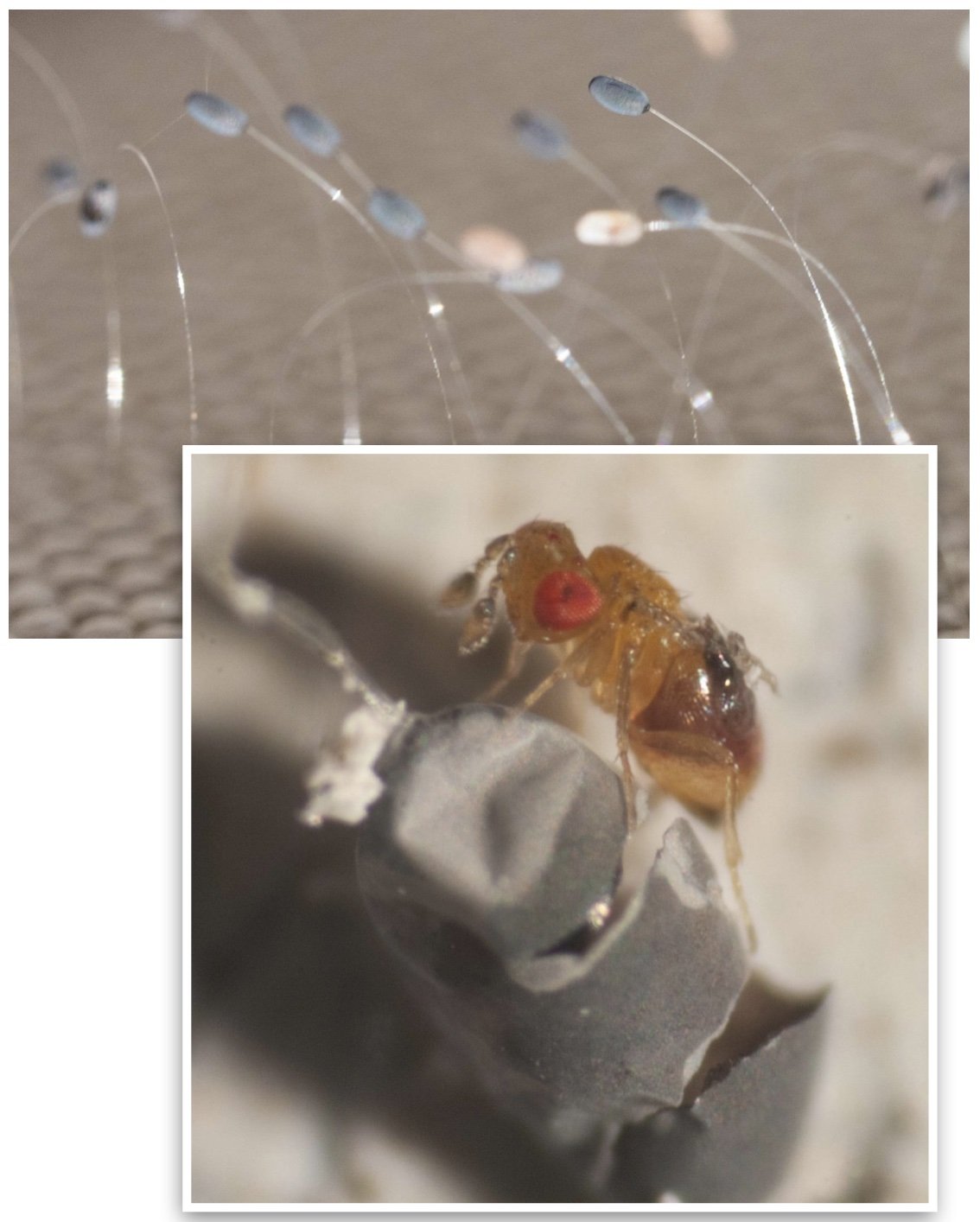

wow!

The host is now completely cloaked in Melittobia larvae … just its head is visible (to the right). Perhaps the feeding parasites can’t effectively penetrate the tougher cuticle of the head capsule. There is so little room that some of the grubs have been pushed away from the host by their siblings.

Compare this scene to that just 6 days before … noting that no new eggs were laid in the interim, as no adults had access to the host. Wow bugs indeed!

After 4 months of doing nothing, development is underway again!

The larvae remained unchanged throughout winter … but are now at various stages of transformation into adult wasps.

The strings are the larval waste, expelled just before pupation.