Biodiversity by DNA

Our patch of forest is now part of a global program sampling insect biodiversity. Over the next year we will be collecting thousands of flying insects for DNA analysis. Some will be species we know well, others will be new to us – and no doubt many will be new to science.

So how did this come about?

Late last year we received an email from Paul Hebert, CEO of the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics at the University of Guelph, Ontario, instigator of the Global Malaise Trap Program (GMP), and founder/Scientific Director of the International Barcode of Life initiative – inviting us to take part. We were both surprised and delighted.

Of course we jumped at the chance!

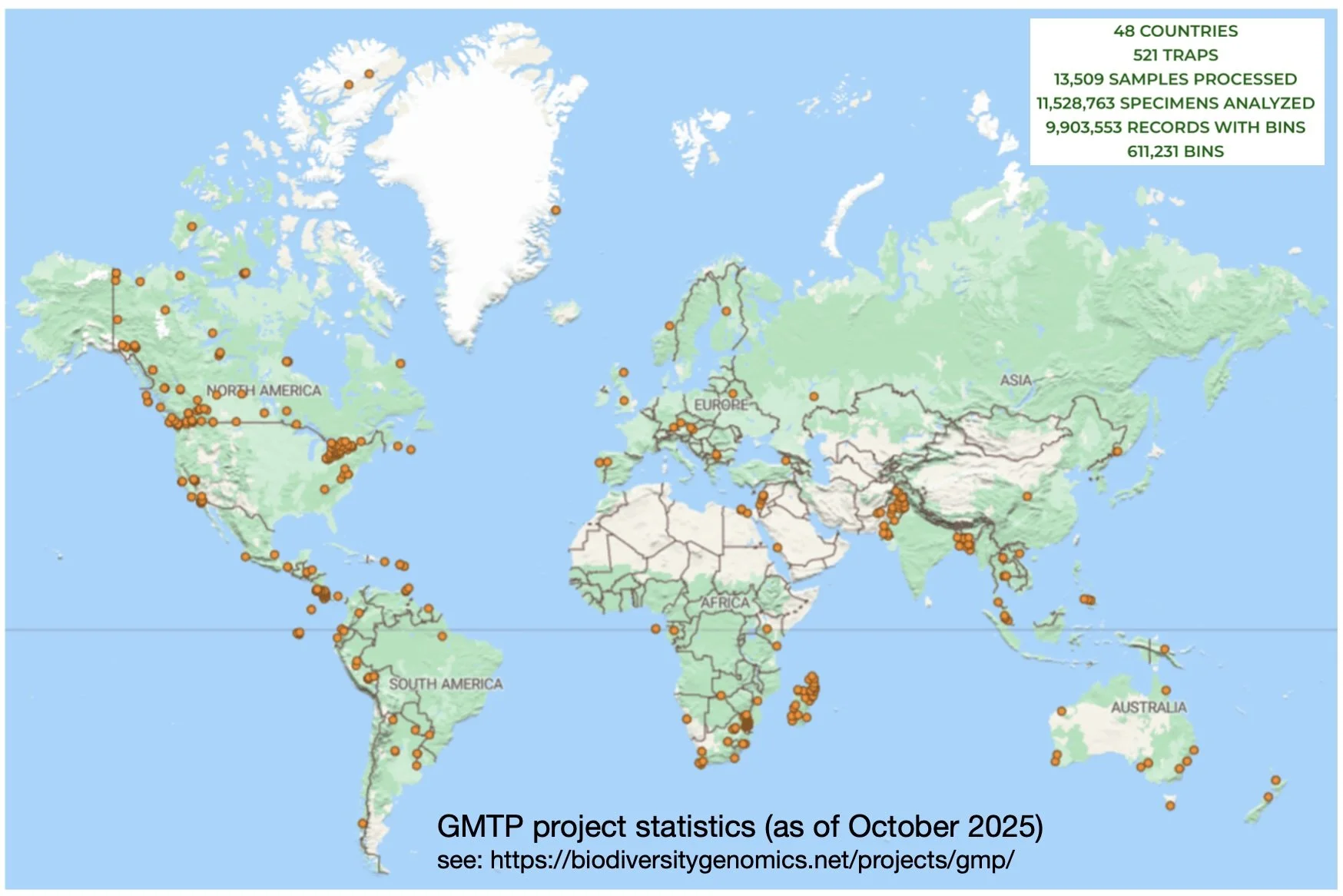

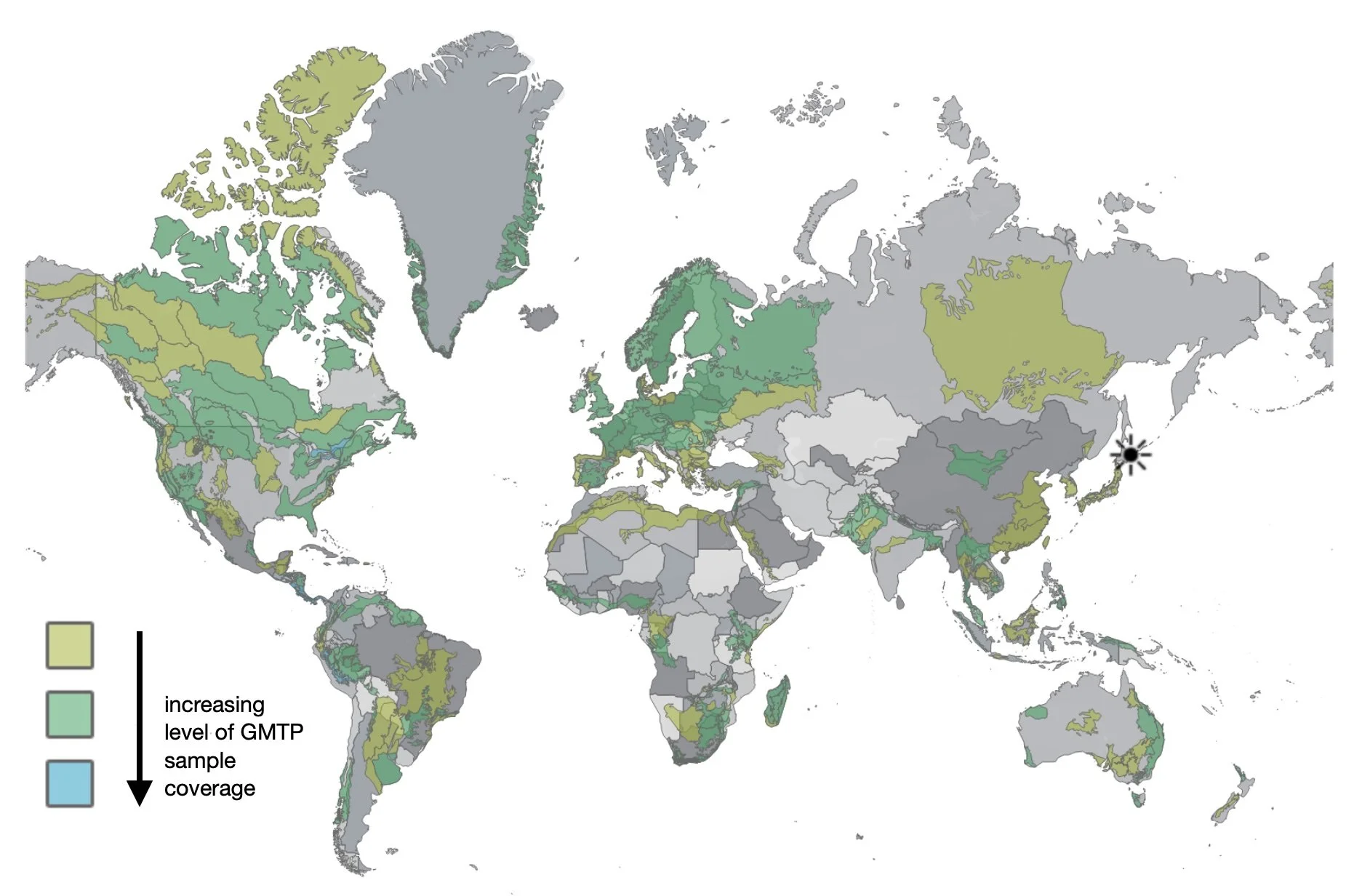

The GMP began in 2012. It now involves nearly 50 countries and hundreds of sampling sites.

"The program represents a major step toward understanding how arthropod communities vary across space and time and how they respond to environmental change." (https://biodiversitygenomics.net/projects/gmp/).

So on 3rd January we set up two Malaise traps, and they are already yielding some impressive results.

What the project is all about

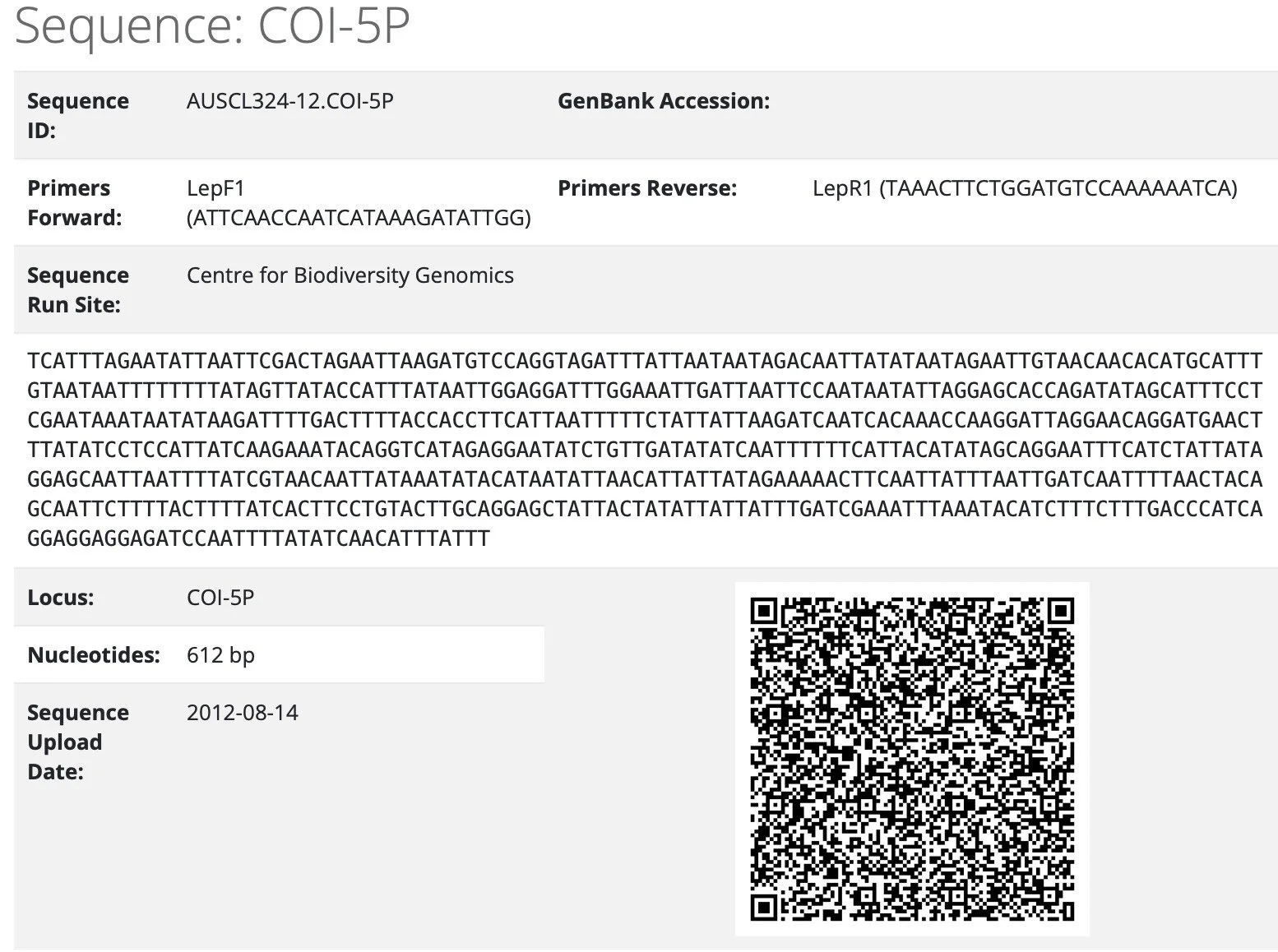

At the heart of the project is a taxonomic tool called DNA barcoding. This method compares short, standardised DNA sequences to distinguish between species.

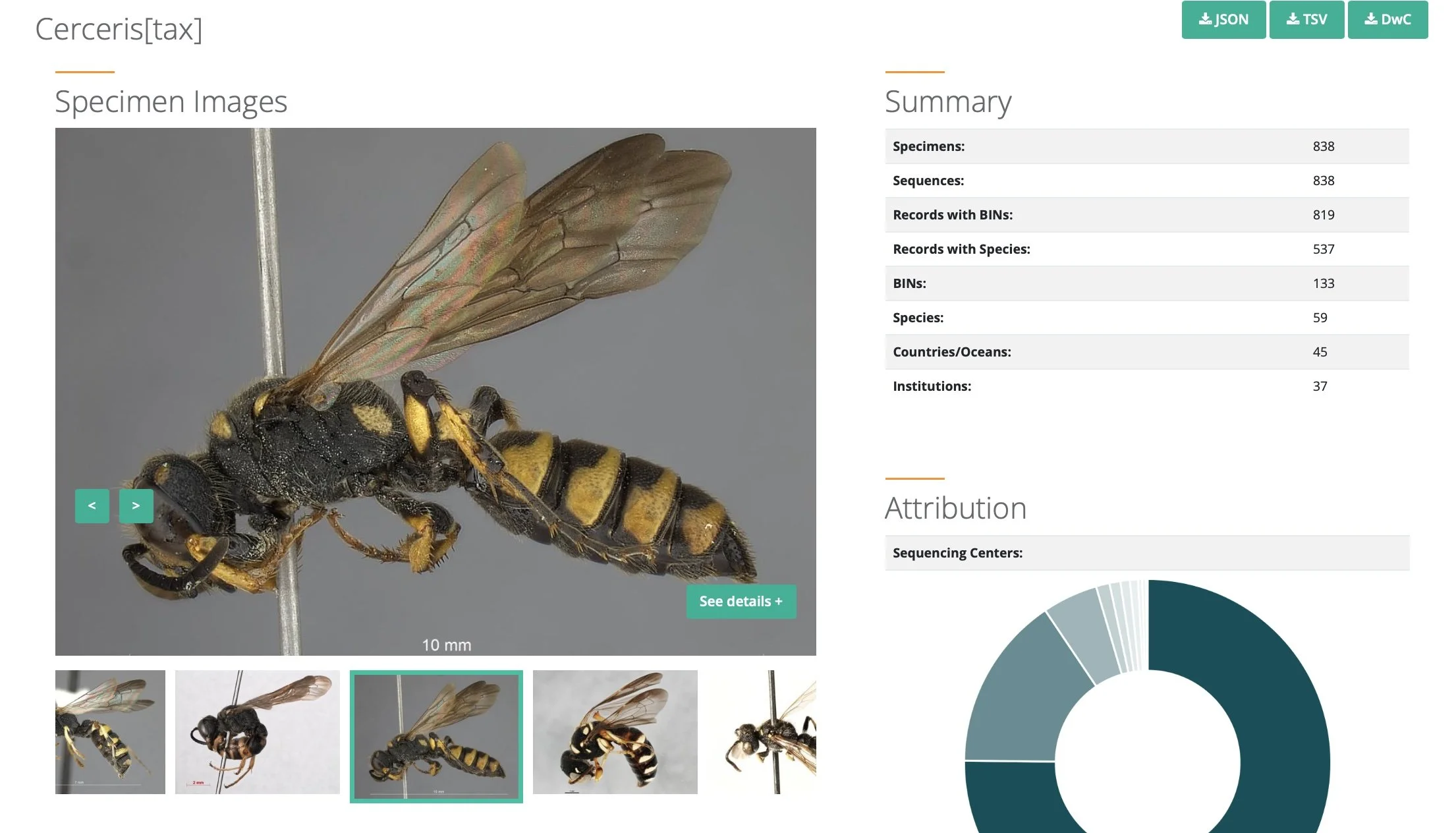

extract from BOLD https://portal.boldsystems.org/record/AUSCL324-12 … DNA barcode for a specimen from South Australia, a crabronid wasp in the genus Cerceris.

Individual specimens of a single species share a barcode. That is, the sequence of a particular stretch of DNA is virtually identical between individuals ... males, females, juveniles or adults. But that particular sequence is unique to that species. For a more detailed explanation (link. https://ibol.org/about/dna-barcoding/).

BOLD – a barcode reference library

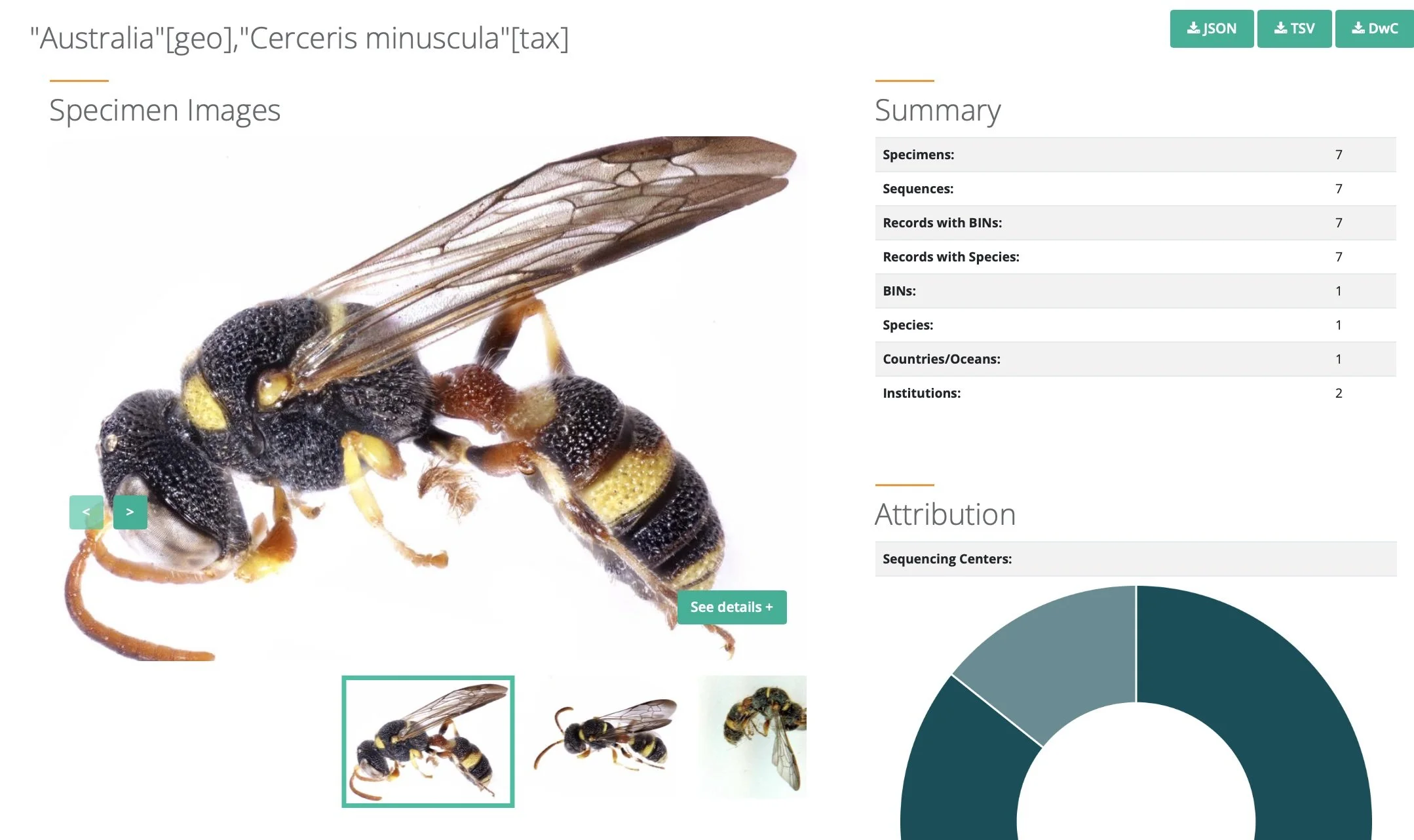

The Barcode of Life Data Systems (BOLD) portal provides access to a suite of web-based resources for publishing, sharing, curating and analysing DNA barcode records. And importantly from our perspective, it provides ready access to this information for the general public. Paul and I regularly check BOLD records for specific taxa, with a particular interest in those with associated images. Indeed, many users of iNaturalist will be familiar with BOLD.

When a specimen record is added to BOLD, the system seeks to match its barcode with those already in the reference library. Sometimes there will be a match, nearly always identified to family, and sometimes to genus or even species (Steinke et al. 2024). Often there will be no match ... and that in itself is informative. It indicates a species not previously 'known' to BOLD.

A species barcode is a powerful addition to the taxonomist's toolkit. It supplements the morphological information that has long been relied upon to describe and distinguish species (Stevens et al. 2011). For example, differences in barcode can uncover a 'cryptic species' - one that appears identical to another, yet is genetically distinct. Conversely, some species are so morphologically varied that they might be considered separate species – yet their barcodes suggest they are one and the same. In addition, similarities in barcode sequence can help determine which species are closely related, and which more distant. Of course, the barcode is only a tiny fragment of the genome. Taxonomists will utilise a variety of genetic markers to further test theories of relatedness.

Global Malaise Trap Program

Specimens and their barcode sequences are input to BOLD from a variety of sources. And one of the major contributors is the Global Malaise Trap Program (GMP).

The GMP is one of a range of projects coordinated by the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics in Canada. The Program’s scope is truly global, seeking to “unite researchers worldwide in monitoring terrestrial arthropod diversity through standardized sampling and DNA barcoding” (GMP website).

A standard survey method is essential if data is to be compared over time, and between places. Importantly, GMP employs the same design insect trap at each site (Uhler et al. 2022) and samples are collected and processed following a specified protocol. Once in place, a trap should not be moved during the course of the study ... which in most cases is 12 months, as it is for us.

The Malaise trap is a passive sampling method, designed primarily to intercept insects in flight. It involves no particular insect attractants, and functions 24 hours a day with only limited need for human involvement. This contrasts with sampling techiques such as light traps, coloured water traps, or sweep netting.

Not all insects are created equal ... at least when it comes to Malaise trapping.

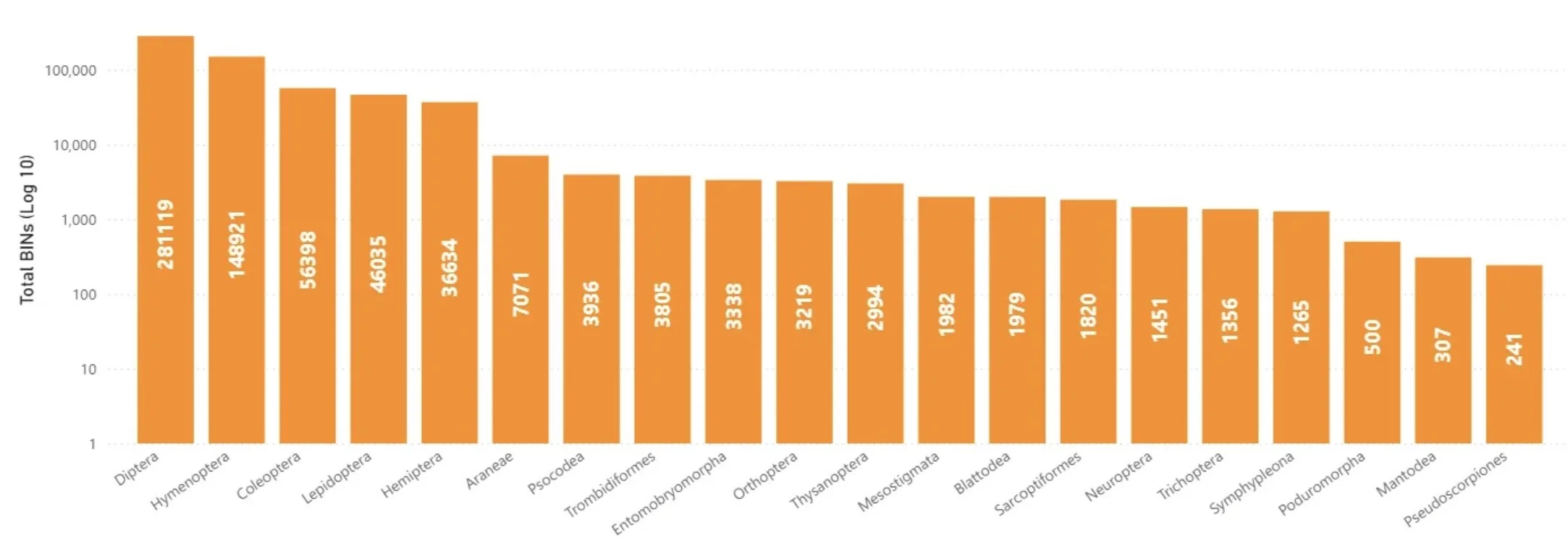

extract from GMTP website https://biodiversitygenomics.net/projects/gmp/ … Project Outcomes (as at October 2025), showing the 20 taxonomic orders with the highest BIN (ie species) counts. Note that this is a log scale.

The most likely to be caught in the Townes-style Malaise traps are flies (Diptera) and wasps/bees (Hymenoptera) (Seymour et al. 2024). Both tend to fly towards light when they strike an obstacle. Upon hitting the barrier net they move upwards to the white roof and from there towards the tent apex and the collection bottle. In contrast, beetles often drop to the ground when disturbed (Uhler et al. 2022). This probably contributes to the marked disparity in catch across these three megadiverse insect orders. For every beetle there are three wasp species, and for every wasp there are two flies!

Despite the ‘flight intercept / positive phototaxis’ model, the traps still harvest a wide range of insect types. Including many wingless species. It seems that some simply climb their way to the top, and then stumble into the bottle.

Our contributions

There are at least three ways in which we can contribute to GMP and IBOL.

1. Bulk samples from an under surveyed ecosystem

We are located on the very far south coast of NSW, largely surrounded by native forests. Our home patch is also relatively undisturbed forest, comprising a diverse mix of almost entirely indigenous plant species. It is a natural place. And as we live on site, we can readily monitor the traps and make weekly collections.

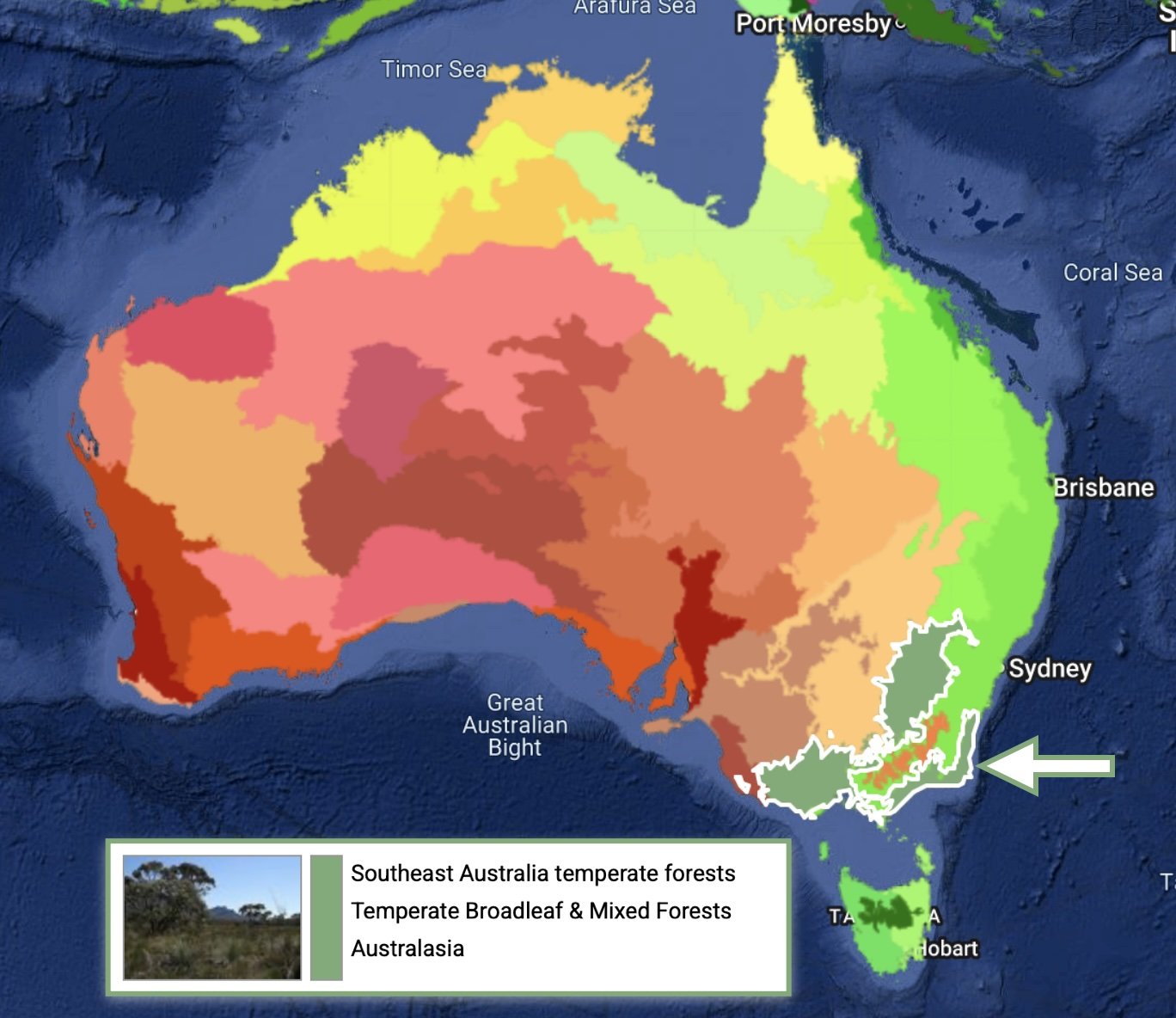

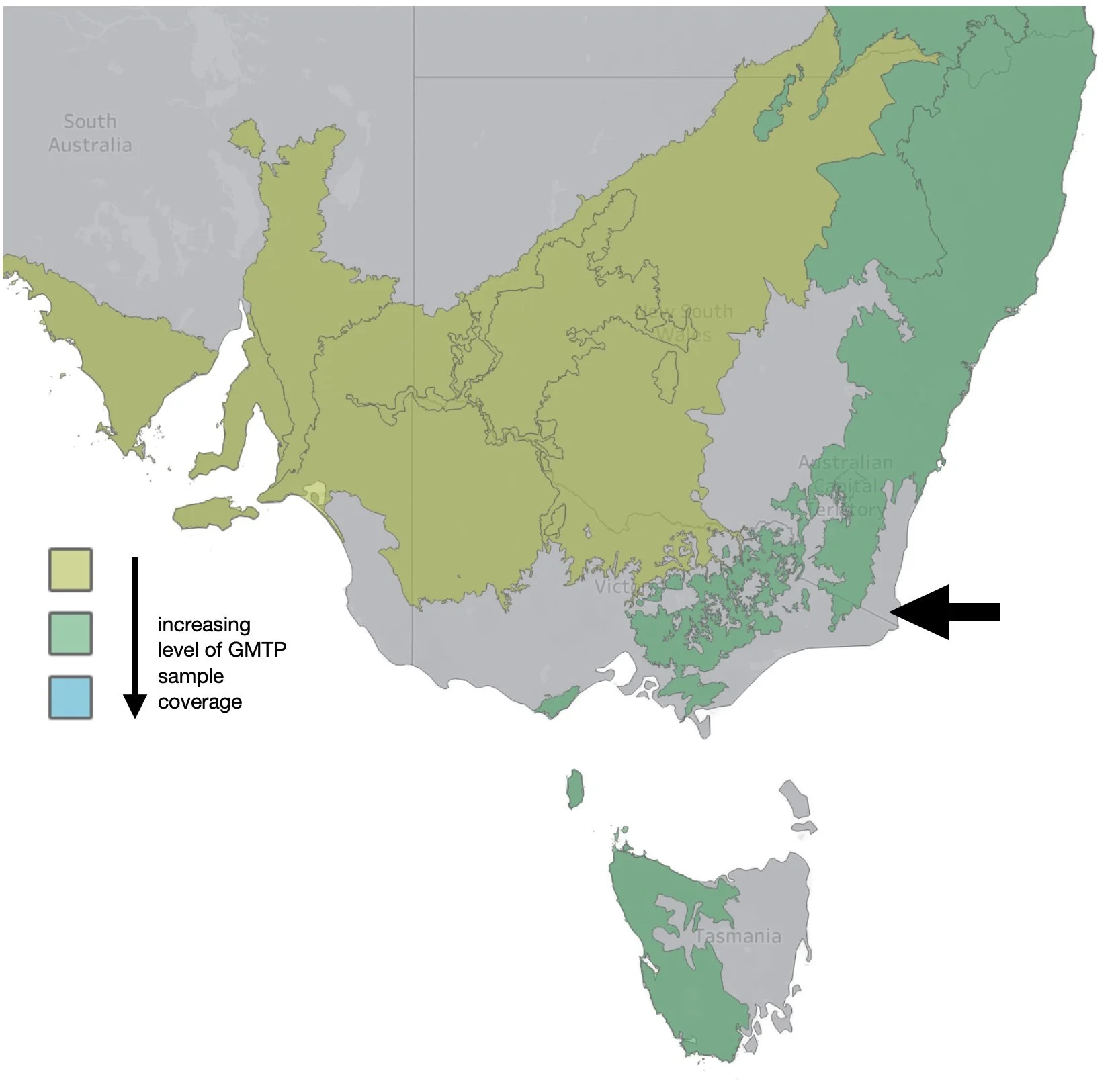

And importantly, our 'ecoregion' has not previously been sampled as part of GMP.

2. Individual reference specimens

In addition to the unidentified insects in the bulk samples, we will be submitting other select insects for barcoding. These will be specimens where we can confidently provide an identification based on their morphology.

3. Knowledge of Australian species

Through our ongoing studies, Paul and I are building our expertise in the identification of particular insect groups. For Paul these are the sawflies, for me crabronid wasps. And for some of these taxa ... the crabronids, in particular ... many of the Australian specimens on BOLD are in need of curation. For those species we know well, and for which there are good images on the BOLD database, we are able to offer suggested identifications. Often this will just be to subfamily or genus, but it all helps to refine the reference database.

Multiple benefits

Our knowledge of local insect diversity will certainly grow through our involvement with GMP and BOLD. For example, we know there are hundreds of species of tiny flies and wasps in the forest .... but just how many? And what families are represented? And how does this change across the seasons?

We will be able to compare our ecosystem to adjacent bioregions. In what ways do the insect biota differ, and what ways are they the same?

In addition, by sequencing select specimens that we have studied in detail, we will be able to compare their barcodes to the BOLD reference library. Is there a match, or to what are they most similar?

And just having the Malaise traps in place has already yielded several specimens we are keen to investigate further! If Paul is very lucky, the traps may yet turn up an interesting sawfly or two ... the adults of which can be frustratingly elusive.

Irrespective of any insights we gain regarding our local insects, simply being part of such a vast, collaborative effort to better understand the biodiversity of life on earth is its own reward.

References and links

Dinerstein, E. et al. 2017. An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience, 67(6): 534–545 open access https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014

Ratnasingham, S. et al. 2024. BOLD v4: A Centralized Bioinformatics Platform for DNA-Based Biodiversity Data. In: DeSalle, R. (eds) DNA Barcoding. Methods in Molecular Biology, vol 2744. Humana, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-3581-0_26

Seymour, M. et al. 2024. Global arthropod beta-diversity is spatially and temporally structured by latitude. Communications Biology 7:552 open access https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-024-06199-1

Steinke, D.; Ratnasingham,S.; Agda, J.; Ait Boutou, H.; Box, I.C.H.; Boyle, M.; Chan, D.; Feng, C.; Lowe, S.C.; McKeown, J.T.A.; et al. 2024. Towards a Taxonomy Machine: A Training Set of 5.6 Million Arthropod Images. Data 9, 122 open access https://doi.org/10.3390/data9110122

Stevens, M.I., Porco, D., D’Haese, C.A. & Deharveng, L. 2011. Comment on ‘Taxonomy and the DNA Barcoding Enterprise’ by Ebach (2011). Zootaxa 2838: 85-88 open access https://www.mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.2838.1.6

Uhler, J. et al. 2022. A comparison of different Malaise trap types. Insect Conservation and Diversity 15, 666-672 DOI: 10.1111/icad.12604 open access https://resjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/icad.12604

![Currently, filtering the search for Cerceris in Australia yields 19 specimens, representing 8 species (as determined by their DNA barcodes … BINS in this summary table). https://portal.boldsystems.org/result?query=Cerceris[tax],Australia[geo]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ec80a8d2b857fe42e4f603/1769731670493-H3PI4JH761F0HJNC9BQD/Cerceris+in+Australia+BOLD.jpg)

![Another example of search results by genus, this one a page Paul has made good use of in his ongoing study of Australian sawflies. https://portal.boldsystems.org/result?query=Perga[tax]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ec80a8d2b857fe42e4f603/1769731681281-JRVLXH6NG6RKB9J6MZ9H/Perga+BOLD.jpg)

![Samples are collected weekly and stored cold (ideally in a freezer). Batches are then shipped to the Centre for Biodiversity Genomics for imaging and sequencing. [image from GMP website ]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ec80a8d2b857fe42e4f603/1769736454642-3FQ4H8JBIZR6U8LF00BR/sample+bags.jpg)

![At CBG, the samples are analysed in detail. This includes a system for imaging individual specimens before sequencing. [extract Steinke et al. 2024, Figure 1, p. 122]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58ec80a8d2b857fe42e4f603/1769736463211-1LMLUJWU96NN68Q0501I/Steinke+Fig+1+extract.jpg)