Autumn fruits

Autumn is the season when, according to John Keats, things come to fruition.

A moth emerges from its pupal case to complete its life cycle. A late-maturing plant produces berries or other fruits. Fungi thrust up their fruiting bodies - mushrooms - from networks of soil hyphae.

But autumn can also mark the start of new life.

Many insects mate at this time of the year. In some cases, their larval offspring hunker down for the coming winter in an inactive form. In others, the larva continues feeding - particularly if it’s a herbivore. Many parasitic wasps select active larvae as hosts in which to deposit their eggs.

A few plants flower, using alternative modes of pollination as insects have become scarce. But most just slow down their growth, waiting for longer days, warmer temperatures and the return of their insect pollinators in spring.

This gallery showcases examples of the many sides of autumn life in the forest.

The developmental journey of two moths

The Batwing Moth - autumn marks the end of a 9 month lifecycle

This story began last autumn when we attracted 17 male Batwing Moths (Chelepteryx collesi: family Anthelidae) to our May lightsheet …

… together with 2 females of the same species. As you can see, she is a large, beautiful insect. She had apparently met up with one of those 17 males (or perhaps another one) shortly before she came to our attention. The evidence? On the lightsheet she deposited …

… this elegant string of eggs. The lightsheet wasn’t the optimal environment for their continued development, so we moved them to our moth (and other insect) rearing cage.

So development starts now!

Pretty soon we had around a dozen caterpillars to care for. They readily accepted Eucalypus leaves and grew apace. They were around 17mm long at this stage. Quite striking creatures, but watch those long hairs! They can break off if you handle the caterpillar carelessly and cause severe skin irritation.

4 months later, the caterpillars had grown to a length of 58mm, passing through a series of moults - like the one shown here with its former skin.

6 weeks later, the caterpillars had grown to around 100mm long. While much larger, they were otherwise little changed in appearance. They became restless soon after, wandering around the cage. Apparently, they are often seen walking along suburban footpaths in Canberra at this stage. In early December, ours started to pupate, building a white, silky cocoon around their bodies.

Then 3 months later, a new adult female emerged from one of the pupal cases. You can see the remnant hairs from the larval body protruding from the surface of the cocoon. So from egg to adult takes a full 9 months in this moth species.

We carefully moved this female outside and placed her on a bush while she was preparing for her first flight. A half hour later she was gone. Perhaps she’ll appear on our May lightsheet this year!

And the cycle starts again! Two male Chelepteryx collesi moths have been attracted to our light sheet tonight - almost exactly 12 months since we last sighted this species.

The Mottled Cup Moth - autumn marks the start of a paused, overwintering stage of development

Kerri spotted a caterpillar of this species (Doratifera vulnerans; family Limacodidae) wandering in the undergrowth on 24th March. It was probably blown out of the crown of a eucalypt during a windy period. Unlike many moth larvae, it has a distinctive enough appearance to determine its species identity with confidence. But we decided to rear it through to the adult stage in our buddy tank anyway.

Fed on a diet of eucalyptus leaves, the caterpillar - shown here on 10th April - grew rapidly. This photo shows the rosettes of stinging hairs which the larva everts when disturbed. These release a cocktail of toxins when touched, producing a stinging sensation (ref. 1). Doratifera vulnerans means “bearer of painful gifts” - an apt name! The caterpillar gives due warning of its toxicity with its bright colouration. Most birds give it a wide berth, although fan-tailed cuckoos and rosellas have developed ways of dealing with this toxicity as they include it in their diet.

24 days later the larva now looks like a gumnut on the twig - hidden in plain sight! The caterpillar will soon enter the pupal stage, during which its body becomes transformed into an adult moth. The emerging moth will escape from the cocoon by pushing against the circular end cap, popping it off. It’s clear where the “cup moth” name comes from.

Kim Sinclair has produced a great YouTube video of the whole process of cocoon formation by Doratifera vulnerans.

We’ll have to wait till next spring to see the emergence of the adult moth from the cocoon. Collett and Fagg (ref. 2) state that in East Gippsland, pupae develop throughout winter and emerge as adults in September to recommence the lifecycle. Our larva has probably paused development at the prepupal stage within the cocoon.

Other moths and some butterflies

Hecatesia fenestrata - the larva of the Whistling Moth, featured in our Summer Sightings blog. Seen here feeding on Dodder Laurel (Cassytha pubescens), on which it will continue to graze over winter. The adults have been reported to emerge in early spring.

Heteronympha banksii - a male defending its territory at the top of a bush. This butterfly only appears in autumn, when it is regularly sighted patrolling sunlit patches around the forest. It lays its eggs on grasses, which the larvae feed on through winter.

Parepisparis lutosaria - sighted on our April lightsheet. Its larvae feed on Eucalyptus. Moths in the genus often lie with their abdomens twisted to the side, resembling dead or yellowing leaves.

Glyphipteryx gemmipunctella - a rather small but beautiful moth with a very long name. We see this moth during the day in early/mid autumn resting on leaves of sedges, flicking its wings open and closed. Sadly, nothing is known about its life cycle. So I can’t tell you what its caterpillar looks like, what it feeds on or the duration of its larval stage.

Amphiongia chordophoides - another April lightsheet moth. This is the first time we’ve sighted this species in our forest. We appear to be at the southern limit of its distribution.

Heteronympha merope - a female resting on the forest floor. The females mate in the spring, but aestivate over the hot summer months, hiding out in the cool gullies. They re-emerge in autumn when they lay eggs on a range of plants, including Themeda and Poa. Their larvae emerge as adults in spring.

Oenosandra boisduvali - the male of this species, shown here, has an interesting speckled pattern on the forewings. It is a sexually dimorphic species - the female has white forewings with a narrow longitudinal stripe of the same pattern as the male’s wings. As befits its name, the adults make their first appearance in early autumn and are gone by the start of winter. The larva feeds at night on Eucalyptus leaves, hiding beneath the bark of the tree during the day.

Oenochroma vinaria - a striking caterpillar, larva of an equally attractive moth, seen here on one of our window screens in November. The larva is seen feeding on Hakea macraeana, which will support its development through to the spring, when it will transform into the adult moth.

Epicoma melanospila - these caterpillars feed gregariously during the day. We found this large cluster in an Acacia longifolia bush. They disappeared suddenly in late autumn. Later stage larvae are reported to be solitary feeders and are widely scattered. The earliest sightings of the adults on iNaturalist are in late spring, so the larvae apparently feed right through winter. We often see the adults from early summer onwards on our lightsheets, displaying its eponymous wing pattern.

Hypocysta metirius - probably our most common butterfly. It is seen throughout the forest in large numbers from mid spring to mid autumn. Their larvae spend the winter feeding on grasses.

Pollanisus subdolosa - a small, but striking moth often seen flying slowly in the forest in early-mid autumn. It can afford to be both conspicuous and slow moving because its body contains cyanide, a product of its own metabolism.

A grab bag of other autumn insects (plus a couple of other arthropods)

Echthromorpha intricatoria - there are many, many ichneumonid wasps in the forest. They become one of the most active groups of insects in autumn, flying here and there searching for a host for their eggs. This one is after lepidopteran pupae.

Xanthopimpla sp. - a small parasitic wasp, often seen in the last month, patrolling the vegetation low in the undergrowth. Like the White-spotted Ichneumonid Wasp, it is searching for a lepidopteran pupa in which to deposit its eggs. Wasps in this genus have been used as a biological control agent for the Light Brown Apple Moth.

Enicospilus sp. or Netelia sp. - we’re not sure which one but it’s definitely in the subfamily Ophioninae of the Ichneumonidae. This wasp often comes to our lightsheets. Species in this subfamily inject their eggs into larval lepidopterans. It includes some of the only parasitoid wasps that can use their ovipositors to sting humans.

Rhinotia lineata - a common but striking weevil, often seen in the forest. Little is known about the biology of the genus Rhinotia but adult weevils in the family Belidae feed on pollen and some are important pollinators. The larvae of some species bore into the wood of Acacia, so it’s probably no coincidence that we saw this adult on a wattle stem.

Chrysolopus spectabilis - indeed a spectacular beetle! We often see it feeding, as here, on Acacia stems and leaves. This was one of the first Australian insects to be described, having been collected by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on Cook’s first voyage.

Leptotarsus igniceps - this is one of many crane fly species we see in the forest. They are often seen hanging from vegetation with their enormously long legs. This appears to be a southern species - we are close to the northern limit of its reported distribution on iNaturalist.

Tapeigaster brunneifrons - a new species for us of a familiar group of flies. These plucky little males take up residence on the cap of a mushroom. I’ve seen other species defending that territory from intrusions by other males, but on one occasion I saw three males of this species sharing a mushroom cap. They mate with females seeking to lay eggs on the gills of the mushroom, which represent a rich food source for their larvae.

Here is an overview shot of the male in position on its chosen Amanita sp. fungus.

Bromotheres australis - these rather small flies are, like other robber flies in the family Asilidae, predators. They impale their prey - other insects - with their needlelike hypopharynx and immobilise and liquefy it by injecting a mix of neurotoxins and enzymes. Nice! They are easiest to spot when still and mating, like this pair.

Torbia perficita - a large katydid which is a frequent visitor to lightsheets in mid autumn. We reared this species from the egg right through to adulthood on eucalypt foliage. You can read the full story in our blog Growing Up.

The adults lay their eggs in a row on a eucalypt stem in autumn and probably die soon thereafter. The eggs overwinter in a state of arrested development, called diapause, and hatch in late October. They reach the adult stage in mid-late January.

Trigonidium sp., close to Trigonidium marroo - a very pleasing little cricket, which became increasingly common in mid autumn. This one is a male. Little is known about their biology, apart from their preferred habitat, which is amongst grasses and forbs.

Bobilla sp. - we always seem to get a burst of these small, ground-dwelling crickets in early autumn and this year was no exception. The male, shown here, produces his mating call by rubbing the tiny teeth on a vein of one of the forewings over the other wing.

Didymuria violescens - our visitor Janet discovered this impressive female stick insect in a low bush. She was probably blown out of the forest canopy in the strong winds. After we collected her to take close-up photographs, she began to drop eggs. We released her, but she will not live for much longer as adults are reported to have only a 2-3 month life span after appearing in late summer.

Here is one of the phasmid’s eggs. She will lay around 200 eggs, which typically hatch in November-December. The nymphs take 2-3 months to develop to the adult stage.

Porcellio sp. - we don’t get many crustaceans in the forest, so it was a surprise to find this one in a rotten eucalypt log.

Argiope keyserlingi - It’s always nice to see one of these in her web with an egg sac.

Birds and other vertebrates

Eopsaltria australis - it took a while for the Yellow Robins to recover after the fire, but they’re now back in good numbers.

Rhipidura albiscapa - an everpresent inhabitant of the forest. We never tire of watching it doing its back and forth dance on tree branches.

Egretta novaehollandiae - this year for the first time, we’ve seen this heron wandering around the block on several occasions. It visits the frog pond but also searches for prey in the forest proper.

Egretta novaehollandiae - it seems to quite like roosting in the dead wattle trees behind the frog pond

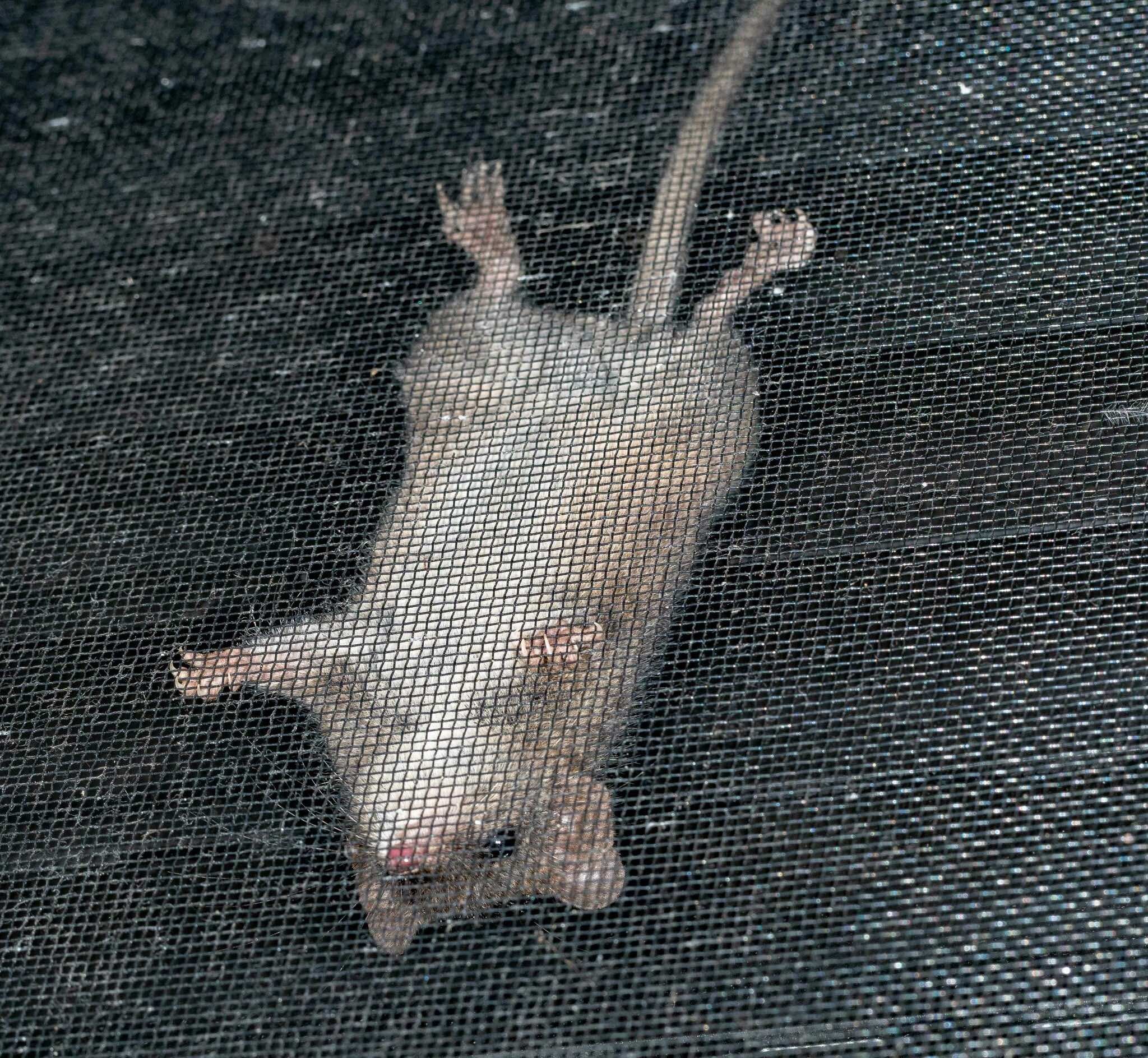

Antechinus agilis - these guys often keep Kerri awake at night as they run back and forth over the flyscreens on our bedroom window hunting insects. I took this photo from my bed on my back looking upwards - hence the rather strange perspective.

Isoodon obesulus - this guy is definitely a resident! We often catch sight of it racing away into the bushes when disturbed. But on this occasion it was nonchalantly digging for worms in broad daylight in front of our kitchen window.

Crinia signifera - the frog pond has been extremely busy this summer and autumn. Lots of tadpoles and loud mating calls of several species. I managed to catch this pair of Crinia signifera in amplexus.

Crinia signifera - very obligingly the pair rolled over to give me a shot of their bellies.

Plants

Correa reflexa speciosa - one of the very few low growing plants in flower at this time of the year.

Acacia terminalis - this wattle has been in full bloom for over a month now and is still going strong.

Acacia terminalis - some bushes are overloaded with blossom!

Trema tomentosa - we have two bushes of this plant and this one currently bears a heavy crop of berries. They turn black as they ripen but should not be eaten as they are reported to be toxic to stock.

Callitris rhomboidea - We lost all of the trees and bushes of this native pine in the January 2020 fire. Their regeneration from seed has been a relatively slow process but some plants are now over a metre tall. This shot shows the mini-forest of seedlings growing from seed dropped by the single killed bush just behind them.

Fungi (note: these identifications are very provisional at this point)

References:

A.A. Walker et al. (2021) Production, composition, and mode of action of the painful defensive venom produced by a limacodid caterpillar, Doratifera vulnerans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118 (18) e2023815118.

N.G. Collett & P.C. Fagg (2010) Insect defoliation of mixed-species eucalypts in East Gippsland. Australian Forestry 73:2, 81-90.