Shetland Islands: the mammals

Up until 12,000 years ago the Shetland Islands, along with the entire northern half of the British Isles, was covered by a thick ice sheet.

As a result, only a small number of different land mammals occur on the islands. All of these were introduced by man, the first people arriving around 8,000BC.

There is also a range of marine mammals, which colonised the waters around the islands as the sea ice retreated.

Some of the Shetland mammals can’t be missed, while others take a bit of finding. We count ourselves lucky to have sighted some of the more elusive species.

The Shetland Pony

Let’s start with the iconic Shetland mammal, one which is not hard to find. Shetland ponies or Shelties, as they are locally known, can be seen all over the islands - generally in small herds like this, which we discovered on a walk not far from our croft.

The black pony in the distance seemed to be keeping lookout. It didn’t move from this position the whole time we interacted with the rest of the herd.

The Shetland pony is a very old breed. It probably resulted from a cross between animals brought to the island by Neolithic people around 2,500 years ago and ponies of Norse settlers, who arrived c.800AD. Considerable effort is made nowadays to maintain the purity of the breed on the islands.

Shelties are admirable work horses. Their thick coats and long, shaggy manes and tails protect them from the severe weather conditions on the Shetlands. They cope well with the low levels of nutrients in the native vegetation.

There was high demand for the breed in the 19th century to replace children for work in the cramped conditions of coal mines. Their main employment nowadays is as steeds for young children at fairs or hobbits on adventures.

Our encounters showed Shelties to be curious and friendly. As adorable as they look, I wasn’t prepared to take any risks and kept a safe distance when patting the ferocious-looking black and white beast. My caution was warranted - it actually tried to nip Kerri when she patted it carelessly!

Shetland Sheep

Another Shetland mammal that is easy to spot - there are around 280,00 of them on the islands! In fact, you have to take care not to hit them when driving around as many paddocks are unfenced. Even when present, fences are readily crossed by the determined Shetland Sheep.

Like the ponies, sheep have a long history on the Shetlands, having been introduced thousands of years ago. In a sense, they are part of the natural ecosystem. The present Shetland Sheep breed is probably a mixture between small, short tailed sheep introduced by Neolithic settlers and a breed of Norwegian sheep brought by the Vikings. The original breed is “unimproved”, meaning it has not been cross bred to achieve a higher yield of wool. As a result, its wool is finer than in cross breeds.

The wool industry has long been an important part of the island economy. The high quality of the fleece and the skills of local artisans combine to produce wool products famous for their style and quality. The traditional design from the Shetland island Fair Isle is famous the world over.

This might seem surprising judging from the appearance of the typical Shetland sheep - “daggy” would be the apt Australian description. Kind of weird that people pay several hundred pounds for a hand-knitted Fair Isle jumper made from the stuff (partially) covering this creature.

If it looks like the wool is falling off this sheep’s back, it is. There is a natural weakness in the wool fibre, which means it is naturally shed in the Spring. This means it can (and is often) pulled off the animal by hand, a process called rooing. Believe it or not, unsuccessful efforts have been made by the Australian wool industry to breed a merino with the same characteristics - no shearing necessary!

Shetland lambs are a much more pleasing sight than their mothers. Their ears are large, their tails long and they’re awfully cute.

As mentioned, sheep are found almost everywhere on Shetland. This group, which we saw on a steep hillside on the eastern island Fetlar, enjoy a great view of the bay below. Picturesque sheep paddocks!

Otters

A much less frequently encountered Shetland land mammal is the Otter, locally known as Draatsi. These may have arrived with the early Norse settlers.

There are about 800 individuals on the islands but getting a sighting requires a good measure of luck and perseverance, due to their elusive nature. A couple of local farmers told us that many visitors come to the islands with the express intent of seeing an otter but are almost invariably unsuccessful.

We were therefore extremely pleased to get sightings of two otters. Both occurred on the same walk where we met the Shetland Ponies.

The locality was ideal otter territory - a sheltered rocky shore with small streams running into the sea. Otters are normally only seen in the early morning or at dusk. It was mid morning when we set out on our walk. But as it was an overcast, dull, misty day we hoped that they would be tempted to get out and about.

We walked for an hour or so without any luck. Then, as we began to head uphill after crossing a stream, Kerri let out a muffled cry to come forward to her. I got to her just in time to see a long, dark brown creature racing down the slope of the hill ahead towards the sea. It was moving in a way I’ve not seen before - kind of a rapid, loping motion. It took us a few seconds to realise we were looking at an otter.

Kerri managed to get her camera onto it just in time to get a few blurry photos - no time to adjust shutter speed!

We could hardly believe our luck in sighting this creature - the first time either of us had seen an otter in the wild. We could not have imagined that we would see another one just a short time later!

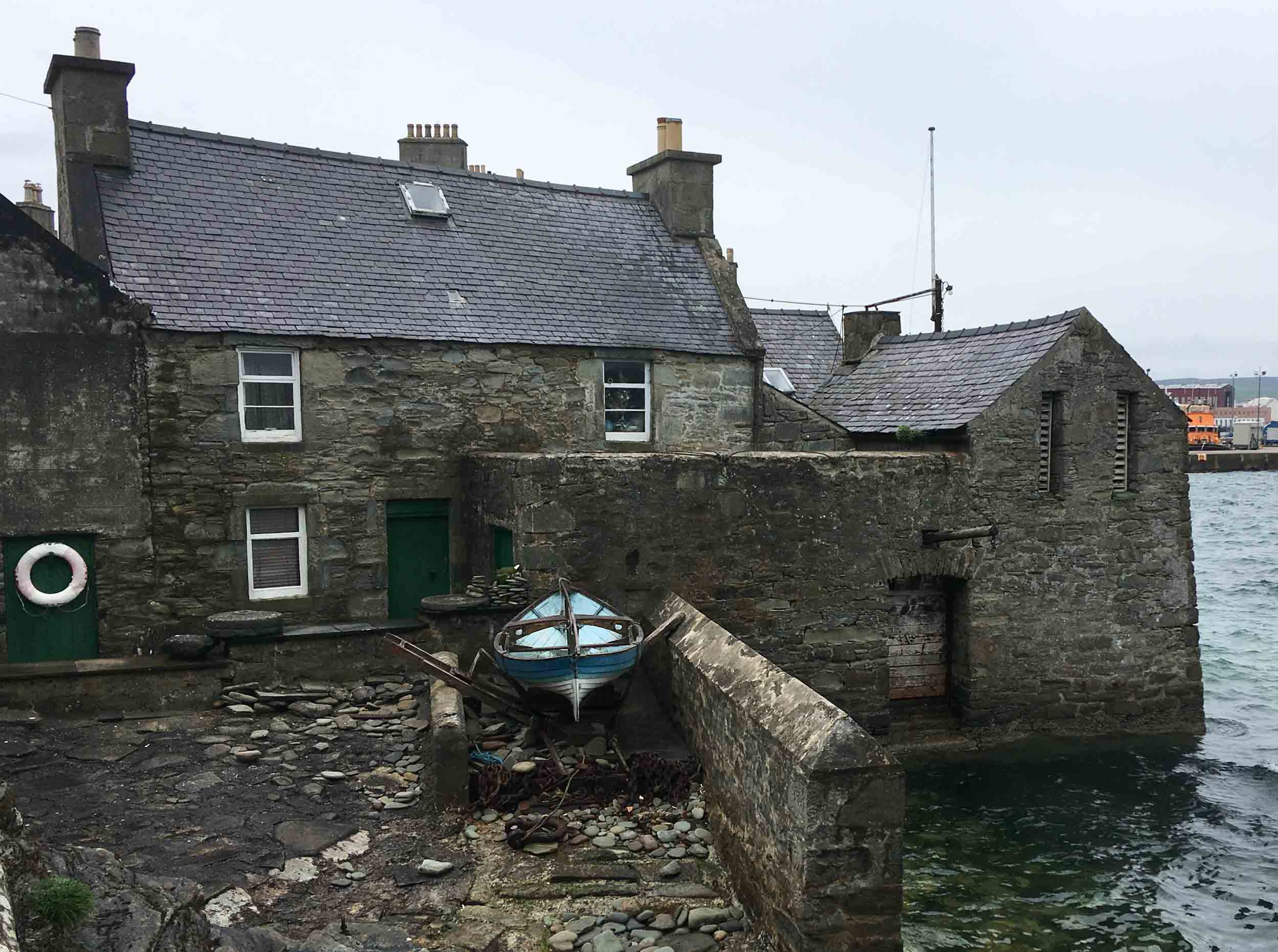

As we headed back towards our car, we came to the small, rocky cove shown below.

As the cove came into view, Kerri let out another muffled cry so again I hurried forward. This time we were treated to wonderful views of an otter swimming out of the waves and crawling forwards onto the rocky shore. It looked up and caught sight of us, whereupon it turned on its heels and dashed back into the water.

This was all over before Kerri managed to get her camera into position. However, once the otter was safely back in the water it bobbed around for a minute or so, giving her time to take a series of photos.

Finally, it dived forwards and disappeared into the depths of the bay. What a treat!

My photo of the otter diving - can you spot its tail?

Having sighted these otters, we realised why we’d been seeing so many empty sea urchin tests and crab shells on the hillsides overlooking the bay.

The otters had been enjoying the views while feasting on snacks collected from the ocean bed.

Otter tucker

These food remains were often seen along the small streams that flowed into the sea - like the one below. Favoured otter hangouts!

This makes sense because otters must come ashore to wash in fresh water and dry their fur. Their coat is not adapted to sea water and will become water logged if not washed regularly.

Seals

Two different species of seals occur in Shetland - the Common or Harbour Seal (Phoca vitulina) and the Grey Seal (Halichoerus grypus).

We thought we’d probably see seals during our stay on the island. A coffee table book on Shetland written by the well-known author Ann Cleeves mentions that the big supermarket in Lerwick is a good place to view them from!

In fact, we spotted our first seal on the same walk where we saw the otters, not far from our cottage. This one was bobbing about in the water a hundred metres or so from shore. Just a head, but a curious head. As we walked back to our car, it followed us, regularly popping its head out to have a gander.

The rounded shape of the snout and the V-shaped nostrils betray its identity - a Common Seal, known locally as Tang Fish. This is a Northern Hemisphere species, found in coastal waters of the northern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, as well as the Baltic and North Seas.

There are thought to be c.26,000 Common Seals in Scottish waters, about 5% of the world’s population.

We managed to sight Common Seals several times during our stay on Shetland. On one occasion, in a sheltered bay near Vidlin on the eastern side of Mainland Shetland, we got a brief view of a mother and calf. They were in the company of a small herd of adults.

It was only towards the end of our stay on Shetland that we saw our first Grey Seal, known by the locals as Haaf Fish. This bull was swimming in the Holm of Skaw, on the far north eastern corner of the island Unst. This is as close to Norway as it is possible to get on Shetland.

The straight head profile and the nostrils set well apart distinguish it from the Common Seal. Adult Grey Seal bulls are also considerably larger than Common Seals.

Scottish waters house around 100,000 Grey Seals - around 36% of the world’s population. The main item in the diet of the Grey Seal is Sand Eels. They therefore compete directly with many seabirds, including puffins, guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes and arctic terns.

A decline in seabird numbers from the mid 1970s to 1990 was attributed to commercial fishing of sand eels. Bird numbers have recovered somewhat since fishing of this species has been tightly regulated.

Orcas

One mammal we didn’t count on seeing during our visit to Shetland, although we knew it occurs in its waters, was the Killer Whale, or Orca. But you never know your luck.

One day we headed out to Eshaness, a popular tourist spot on the far western side of a long peninsula called Northmavine on the north-western side of Mainland Shetland. The main attraction here are the spectacular cliffs that face the deep waters of the North Atlantic Ocean.

As we walked towards the cliff tops from the parked car, Kerri let out another of her cries - this time not at all muffled. Killer Whales! We both ran forwards to get a look through the binoculars. We could clearly make out a female with calf.

She then ran back to retrieve her monopod which I had dropped on the ground after I had rushed forwards in response to her call.

She managed to get her camera into position and took several shots before the Orcas disappeared into the depths of the ocean just a few minutes later. We spent another hour and a half wandering along the cliff tops of Eshaness and saw no further sign of them.

This was the first time either of us had seen an Orca - magic!