Woombah: life in a more northern forest

23 Dec 2021 – 3 Jan 2022

For a week or so in mid-Summer, while visiting family, we investigated the small creatures living on the edge of a rainforest. And it was quite a haul …

More than 150 different species of insects and spiders, over half of which we have never seen before!

Woombah is a small village on the southern edge of Bundjalung National Park in the Clarence Valley, northern NSW - 930km and 8° of latitude north of our southern home forest.

The vegetation is a mix of dry sclerophyll forest and sub-tropical rainforest. We were fortunate to be surrounded by nature throughout our stay. So we wandered about during the day, between rain showers, photographing all that we found. On two nights we put up a lightsheet for moths and other nocturnal insects.

For a complete species list, including a few birds and plants, see our observations on iNaturalist.

For summarised highlights, read on …

Moths galore!

We expected to see moths, given the natural environment and the season. But conditions were challenging, with rain both nights limiting surveying to just a few hours. Yet the results exceeded our expectations.

A total of 76 different moth species from a wide variety of families!

Some species were familiar to us, but most were not. Here are few of the 35 additions to our moth life list:

Many of the species that were new to us on this trip might be present in our southern forest. Perhaps we have just yet to see them. Or perhaps they need different microhabitats.

However, for a dozen of these new species Woombah is at the most southern extent of their usual range – most notably, 9 of the 13 Erebidae. No chance of ever seeing those ones at home in Wonboyn!

One of the more spectacular Erebidae was Donuca rubropicta … a species typically only found in coastal south-east QLD and north-east NSW. The larval food plant for this species is not known but given the species’ restricted distribution, it is likely to be a plant endemic to the region.

Another of the Erebidae of interest is Hyposada hydrocampata. There are very few records of this species in Australia. It is also known from Asia, but sightings are rare there too. There are just 37 records on iNaturalist, including the 20 from Australia. Well, 21 now!

Tropical butterflies

The most obvious and colourful insects were the butterflies. Flashes of brilliant blue, orange and yellow, constantly on the move. We managed a good look at some in the brief moments that they landed, either to lay eggs on low vegetation or to rest during rain showers.

Twelve butterfly species, only three of which are ever seen in our southern forests. One of the joys of a trip to the sub-tropics.

Beetles, and again many new ones

Most of the beetles we saw were unfamiliar. That’s understandable for the tropical species … they don’t extend to our home forests. But others do and yet we’d not seen them before. I guess that’s the nature of beetles. There are many of them out there, and they spend most of their lives hidden away somewhere as grubs.

One sighting was particularly special.

Repsimus aeneus is a large and eye-catching insect, with a range extending from Cairns to Melbourne.

Repsimus aeneus

But recorded sightings are rare, particularly in recent decades.

There are just 294 records and around 40 photos of Repsimus aeneus on the national biodiversity database, the Atlas of Living Australia (ALA). The vast majority of these records are from older museum collections. In contrast, there are 1,520 ALA records for the Christmas beetle Anoplognathus porosus – a beetle with a similarly wide distribution but which is smaller and certainly less spectacular.

Repsimus aeneus

Diversity of lacewings and ‘grasshoppers’

We were especially struck by the diversity of both Neuroptera and Orthoptera. Six species of lacewings (Neuroptera) from three families, and nine species of orthopterans (grasshoppers, katydids etc) across five families!

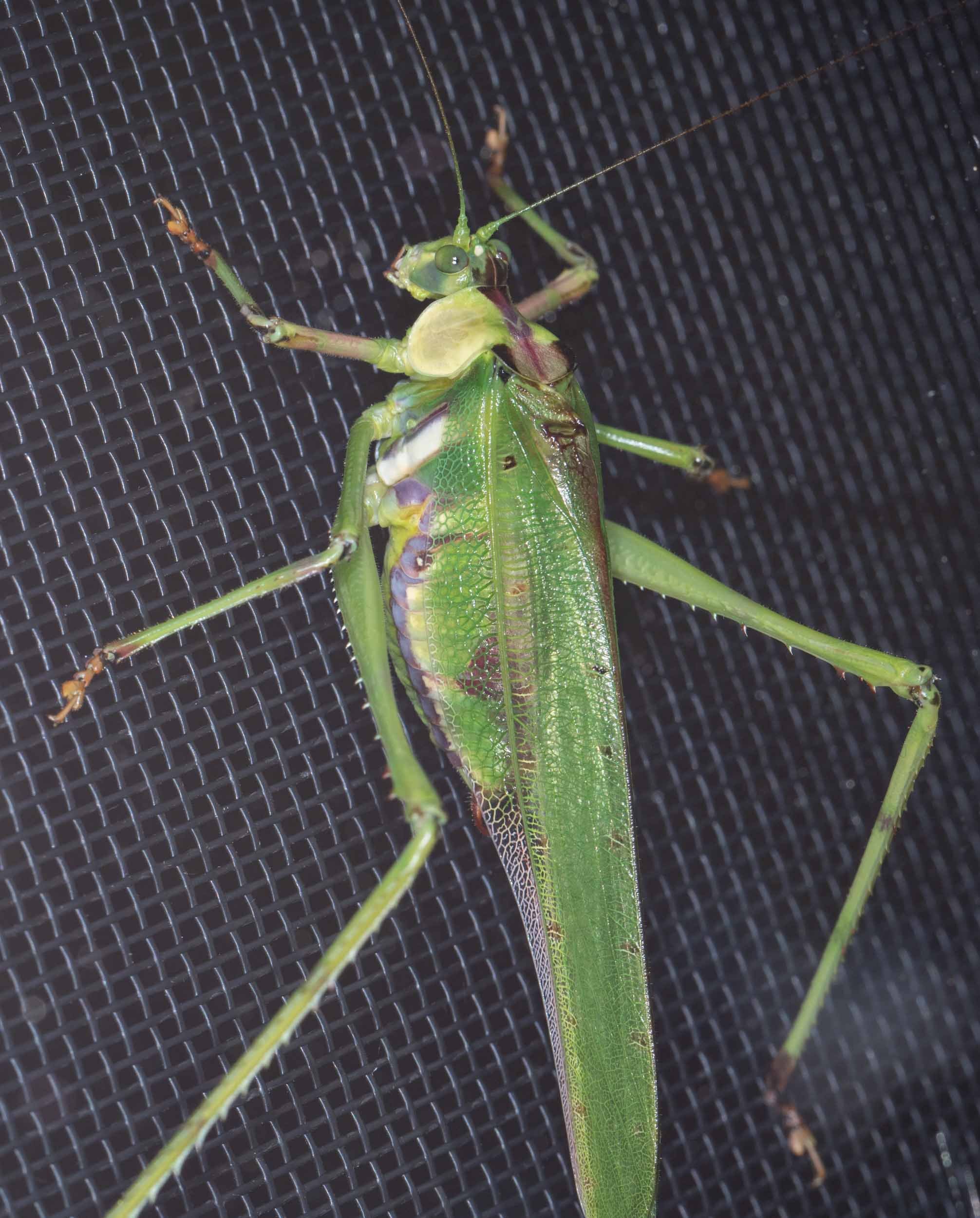

Easily the most significant sighting of the trip was the spectacular Semi-crested Katydid, Protina guttulata (below). We saw just one, attracted to the lightsheet. An exciting find, even before we realised the significance. It turns out that this is a rather rare beast!

It is an eye-catching insect. Huge, yellow, and with very impressive ornamentation behind the head. A photographers’ delight. So it came as a surprise to discover that ours are the first photos to appear on iNaturalist and the first record on ALA. It must indeed be rare! Confirmation can be found in David Rentz’ well-known field guide, where he notes that “this species is very uncommon and is known from only a few localities” (p. 160). Further evidence for the special character and importance of Woombah’s forest environment.

A rather fascinating little bee

I noticed a cloud of tiny, black insects regularly gathering on a Spathiphylum flower. The plant was one of the few non-native species, planted in a garden. Yet it was clearly attractive to these tiny natives. Day after day, whenever I checked, the little bees were busily scraping at the unusual flower spikes.

This was a kind of bee I’d long hoped to encounter, and one that isn’t found in our southern home region. ‘Stingless bees’, the tribe Meliponini, includes just 11 species. These are the only Australian bees that are truly social. They have a queen, live in large colonies, build complex hives, and store pollen and nectar in special cells. And they are tiny … less than 5mm long!

I feel confident that the species is Tetragonula carbonaria. The shape of the thorax, all-black body colour, and distribution (south, into NSW) is a fit, and rules out most other possibilities. Tetragonula carbonaria is also the most common and widespread species of stingless bee.

Although their hive structure isn’t well suited to commercial harvesting of honey, there is some interest in farming these bees for ‘sugarbag’ honey … or simply for general interest in the species. Personally, I was simply delighted to see them up close, and for the first time. Hence, many photos!

’Queen of the Huntsman’

That is its name, seriously! The common name, anyway. More accurately, it is Pediana regina.

This is a rather delicate but long-legged spider. But then again, this one is a male … the female has a much larger body! Its normal home is under bark in eucalypt forest … but we spotted him several times on the pool deck. Perhaps there was a female hiding nearby.

We have yet to see this species at home, but we may … while it is widespread in Queensland, it is also known from other states including Victoria.

A very persistent mud dauber wasp

It seems that mud-nesting wasps are a theme for us lately. Having studied several species at home in recent months, we travel north to find … more mud wasps!

Mud wasp nest #1

This one will be the subject of a later post. The impressive nest had to be removed from the rear vision mirror of my parents’ vehicle in nearby Maclean … so we brought it home with us to Wonboyn for further study. As you do.

So more about this one as events unfold. Hint: I suspect that some of the cells have been parasitised, as the cocoons look different. Intriguing!

The massive, multi-celled nest after we carefully pried it look from the vehicle. Conveniently, we can now see inside each cell, and at the time of collection 9 of the cells contained pupae … along with various spider remains.

Overall length: 14cm. Weight: 130g. An impressive construction by a single, small builder!

Mud wasp nest #2

And then there was the colourful wasp busily building mud nests on the outdoor furniture back in Woombah.

In lifting the seat cushions one day we inadvertently tore apart a smooth, pale-grey cell … revealing a collection of paralysed jumping spiders! Despite looking closely at the spiders, we found no egg or larva. I assume it fell off and was lost when the nest broke open. A second, unfinished cell alongside the first was completely empty.

The following day she was starting over. At least we assume it was the same female. Different chair this time, but the nests look identical and apparently using the same source of grey sand in their construction.

Here she is in action …

Identity? Looks to be Sceliphron formosum (family Sphecidae). Her stash of jumping spiders is extra evidence of her identity. Jumping spiders (family Salticidae) are reportedly the favoured prey of Sceliphron formosum (Callan, 1988).

We watched on as this mud-dauber wasp (Sphecidae) constructed nest cells on the outdoor furniture. Here she is confused by the relocation of her nest chair … fruitlessly searching the chair placed where hers should be!

During lunch, the chairs were dragged about and ‘her chair’ moved aside to be replaced by another. When she next returned she searched and searched the new chair for her nest. Clearly it was the location she remembered, and only when we restored her chair to its original position did she settle in again and continue building. Apparently oblivious to her growing crowd of interested onlookers!

And just a few more

To conclude, here are just a few more of the many, many insects and spiders that we were treated to during our visit.

Our family is truly fortunate to live surrounded by such biodiversity.

And we feel privileged to share in the wonder.

Please note that the species identifications above are always tentative. They are our first, best attempt to work out who’s who. All sightings are on iNaturalist, and it is there that any changes, corrections or refinements will be made in the future. Click here to search the list of sightings made during this trip.

Reference

Callan, E. McC. 1988. Biological observations on the mud-dauber wasp Sceliphron formosum (F. Smith) (Hymenoptera: Sphecidae). The Australian Entomologist, 14(6), 78-82.

Rentz, D. 2010. A Guide to the Katydids of Australia. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic.