Birds of southwest WA: biodiversity on display

Australia has a spectacular level of diversity of both plants and animals. This becomes apparent when you travel to a new area and spend time looking at nature. We’ve spent the past two months doing just that.

Our appreciation of the biodiversity of our continent has been heightened by the fact that the area in which we’ve spent most of our time - southwestern WA - has an unusually high level of endemism of both plants and animals. This means that it is home to many species that are found nowhere else.

It’s therefore unsurprising that many of the organisms we encountered on our trip are different to anything we’ve seen before. Lots of new stuff to look at, appreciate and seek to understand.

Kerri has dealt with the biodiversity of southwestern WA plants in her blog. I’ll talk about the fabulous new birds we encountered.

WA endemic species

The diversity of birds in southwest WA, unlike the plants, is not necessarily any higher than other parts of the country. But the birds on display here are different to those we’ve seen previously.

Why? Well, for many species of birds, the Nullarbor Plains have been a long-standing barrier to interchange between the southwest and the east, allowing evolution to proceed along different courses in those regions. This has resulted in a relatively large number of endemic bird species (16) in the southwest.

We were fortunate to find 14 of these endemics on our trip, 12 of which are shown in this photo gallery. We didn’t get photos of the Noisy Scrub-bird or the Western Corella but made definite sightings.

I’ve included a photo of the montanellus subspecies of Rufous Fieldwren, because until recently this was considered to be a separate species - Western Fieldwren. (The decision as to whether a species of bird is actually a ‘full’ species or just a subspecies can go back and forth, depending on the quality and interpretation of morphological and genetic data. That’s a topic we’ll discuss in depth in a future blog).

There are two WA endemics that we did not see on our trip - Western Ground Parrot and Western Wattlebird. As there are thought to be only around 110 individual birds of the Western Ground Parrot left and almost all of them are in a section of Cape Arid NP that is currently closed to the public, we don’t feel too bad about missing that one. But we have no excuse when it comes to the Western Wattlebird. This is a widespread, moderately common species, but we gave its search a low priority. And then it was too late and we missed out (sigh).

So, how special are these WA endemics, anyway?

Some of these WA endemics are very similar in appearance to species found elsewhere. For example, it takes a keen eye to pick the difference between the Western Bristlebird or Western Whistler and their counterparts in the east, the Eastern Bristlebird and the Golden Whistler.

The Western Thornbill is pretty much a replica of the Buff-rumped Thornbill, except that it lacks the buff rump. The latter is distributed widely in the eastern half of the continent.

The WA endemic Red-winged Fairy-wren is so similar to both the Blue-breasted Fairy-wren and the Variegated Fairy-wren that getting a positive ID on these species in areas where they coexist is challenging.

However, the difference in appearance between male Eastern and Western Spinebills is more obvious.

We also noted an interesting difference in the abundance of Eastern and Western Spinebills. There were few Western Spinebills, when they were present, in the places we visited. In contrast, Eastern Spinebills tend to be quite abundant when you’re in the right habitat on the East Coast.

The jizz of the two species - how they fly and feed - is, however, identical.

The difference between the Red-eared Firetail and its eastern counterpart, the Beautiful Firetail is also not hard to pick. (Hint: look for the red ear).

The White-breasted Robin would be a dead ringer for an Eastern Yellow Robin if you took a yellow texta to its breast. It actually belongs to the same genus, Eopsaltria, which includes only one other robin - the Western Yellow Robin.

At the other extreme, there is no other bird, in the East or West, that even remotely resembles the Red-capped Parrot. This is reflected in the scientific name of this species, Purpureicephalus spurius - this is the only species in this genus.

Baudin’s Black-Cockatoo and Carnaby’s Black-Cockatoo are very similar in appearance to the Yellow-tailed Black-Cockatoo - apart from the obvious difference that the WA birds are white in the places where the latter is yellow.

There is however an interesting difference in behaviour between the two WA Black-Cockatoos. Carnaby’s has a varied diet, eating seeds of a range of plants, including Eucalyptus, Hakea and Grevillea species, as well as exotic pines. In this respect, Carnaby’s is similar to the Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo - at least the nominate subspecies funereus, which is found on the East Coast.

In contrast, Baudin’s Black-Cockatoo has a very restricted diet, eating almost exclusively seeds of Karri and Marri eucalypts. They use the enlarged tip of the upper bill to extract seeds from the fruit of those plants. This reliance on a single food source is similar to the Glossy Black Cockatoo, which eats only seeds of casuarina ‘cones’.

Indeed the jizz of Baudin’s reminded us a lot of the Glossy Black. Both feed quietly high up in the food tree, generally in small groups. Their presence is betrayed by the sound of fruit hitting the ground after the seeds have been removed - the large, heavy Marri fruit in the case of the Baudin’s, the smaller, lighter casuarina cones in the case of the Glossies.

‘WA plus’ endemics

There is a set of south-western WA birds whose distribution extends into western parts of South Australia, but no further. Such species include Western Yellow Robin, Rufous Treecreeper, Blue-breasted Fairy-wren, Nullarbor Quail-thrush and Western Whipbird. The extent to which they creep into SA varies with the species.

The Nullarbor Quail-thrush is found only in the Nullarbor Plains, which straddle the SA/WA border. We were fortunate to sight this species on a late afternoon drive along a dirt track just to the west of the Nullarbor Roadhouse. Kerri took a photo through the windscreen of our car, which was good enough to confidently identify the species, but not good enough for her to grant me permission to reproduce it here. It is very similar in appearance to, and in fact was only recently split off from, the Cinnamon Quail-thrush. The latter is found further east, in the arid regions of central and north-western SA.

The Western Yellow Robin and Blue-breasted Fairy-wren make it right across to the Eyre Peninsula. We found the Western Yellow Robin in a number of places in south-western WA. It is quite similar in appearance to the Eastern Yellow Robin and has an apparently identical feeding behaviour - sitting stationary on a vertical branch, before dropping suddenly to grab a prey item on the ground, then flying back up to a tree to kill/eat it.

As mentioned above, the Blue-breasted Fairy-wren is very similar in appearance to the Variegated Fairy-wren, which is widely distributed from the west to the east coast. The two species overlap extensively within South Australia.

The Western Whipbird has an interesting, disjunct distribution. Different subspecies are found in south-western WA, on the tips of the Eyre and Yorke Peninsula and Kangaroo Island. We heard the loud, distinctive calls of the WA subspecies Psophodes nigrogularis oberon at a number of places. But our only sightings, and they were brief, were at Cheynes Beach.

The Western Whipbird is quite different in appearance to the Eastern Whipbird. Most obviously, it lacks the black head of its eastern counterpart.

But its call is entirely different. Listen to this short video I made of the Western Whipbird calling near East Mount Barren in Fitzgerald National Park and you’ll see what I mean.

A very interesting call, but it shows no evidence of the distinctive ‘whip-crack’ of the eastern species. Typically, this bird called for some time, but never granted us the privilege of a sighting.

The Rufous Treecreeper has a very interesting distribution, as shown in this image I’ve reproduced from The Australian Bird Guide.

We sighted it in south-western WA and also at the eastern limit of its range, in Gawler Ranges NP in South Australia.

Its body shape and general behaviour - running up trunks and branches in search of insects - is like that of other Australian treecreepers, although its rufous colouration is quite distinctive. It does tend to forage on the ground a lot, but it shares that characteristic with some other treecreepers, such as the Brown Treecreeper.

The Rufous Treecreeper is the only treecreeper species found in south-west WA. Yet it appears to be uncommon - we only encountered it on two occasions in WA even though we were often in what appeared to be appropriate habitat for such a bird. This is quite a different situation for treecreepers on the east coast, which are commonly found in most environments with trees, including mallee, woodland and forest.

WA endemic subspecies

Apart from the WA and ‘WA-plus’ endemic species, there is a host of western australian birds - at least 22 - that are very similar to species found elsewhere in Australia, but that show minor differences in appearance or behaviour. This has led to them being assigned subspecies status.

This gallery shows some of these WA endemic subspecies. Each of these is found in only a restricted region of the southwest of WA. Click on each image to view the scientific name, which includes the subspecies name.

In almost all cases, the differences in appearance between the WA and eastern subspecies is quite subtle - usually just a difference in the intensity or tone of a plumage colour.

But there a several cases where the difference is more noticeable. The belly of the WA subspecies of the Crested Shrike-tit is white, whereas in the eastern subspecies it is yellow. This will probably lead to the WA subspecies being given full species status in the future.

The WA subspecies of the Hooded Plover has an extensive mottled black mantle, whereas the eastern subspecies has a narrow solid black mantle.

The white cheek patch on the WA subspecies of the White-cheeked Honeyeater is noticeably smaller than the one on the eastern subspecies.

In most places we visited, a high percentage of the birds sighted were endemic WA subspecies - another reflection of the special nature of WA birds.

It takes a long time to make a species or subspecies

While these differences between subspecies are minor, they are real and reflect an early stage of evolutionary divergence. Over time, and we are speaking hundreds of thousands to millions of years, this will lead to the different subspecies becoming clearly different in appearance and behaviour. It takes a long time to make a new species!

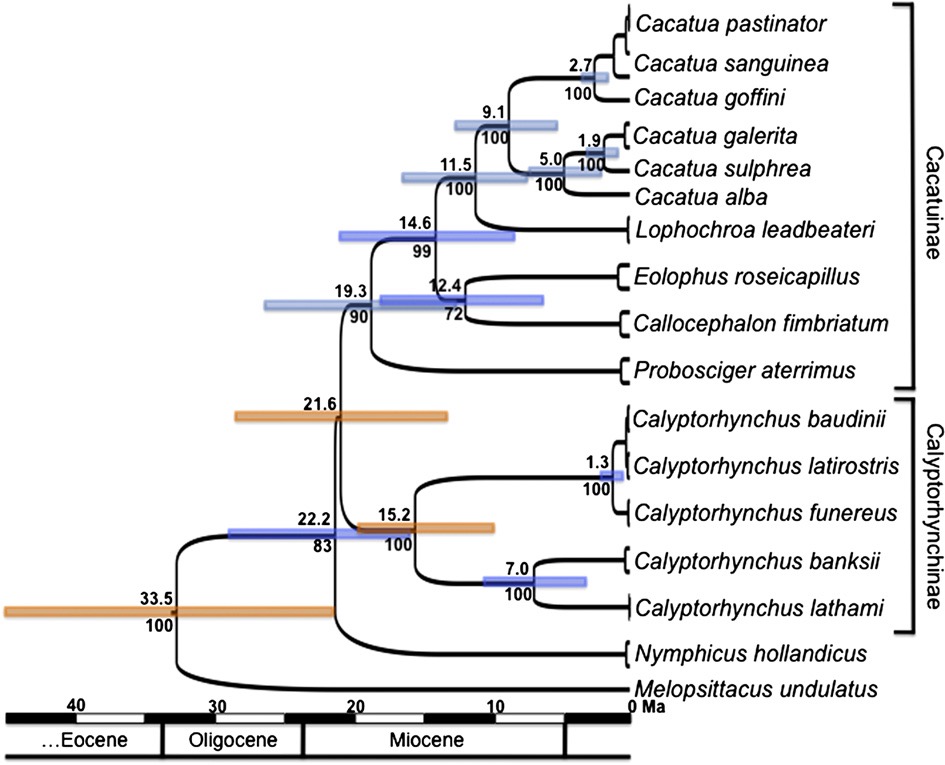

As an example, a 2011 study (reference below) showed that Baudin’s (Calyptorhynchus baudinii) and Carnaby’s (Calyptorhynchus latirostris) Black-Cockatoos split from their closest relative, the east coast Yellow-tailed Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus funereus), around 1.3 million years ago. This was when the southwest corner of the continent became isolated from eastern parts by the Nullarbor Plain.

This diagram from that paper shows the timing of cockatoo evolution as a group, as well as their evolutionary relationships. You may need to consult a bird guide or app to get the common names of the various species.

You may be surprised, as I was, by how long ago these evolutionary splits occurred. For example, the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus banksii) split from the Glossy Black Cockatoo (Calyptorhynchus lathami) 7 million years ago.

For me, this is a salutatory reminder of how precious biodiversity is. It takes a very long time to ‘make’ and when it’s gone, it’s gone.

Birds that are missing from WA

Finally a comment on birds that we didn’t see in WA - thankfully! The introduced European birds -House Sparrow, Common Blackbird and Common Starling - haven’t yet made it across the Nullarbor.

The Noisy Miner, which dominates many natural environments in the east is also absent from WA. In many areas of the southwest, the New Holland Honeyeater and the Red Wattlebird play a similar domineering role: although not to the point where they exclude virtually all other species, as does the Noisy Miner.

Reference:

White et al., 2011. The Evolutionary History of Cockatoos (Aves: Psittaciformes: Cacatuidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 59: 615-622.