Baby food - rearing fairywren nestlings

The Superb Fairy-wren is one Australia’s best known and loved birds.

Intensive research over the last 30+ years - most of it carried out at the Australian National Botanic Gardens in Canberra - has uncovered the complex, truly extraordinary breeding system of this iconic bird (Cockburn et al., 2003; Dunn & Cockburn, 1999).

Like all fairy-wrens, superbs live as a family group, cooperating in breeding tasks and the defence of their territory.

All of the group’s offspring are the progeny of a single female. Her nominal mate is the dominant adult male of the group. However, he sires only a fraction of her children – the rest are the result of matings between the dominant female and males from another territory (known as extra-group matings).

The female’s daughters help with the care and feeding of young. But after they become reproductively mature they are forced to leave the group and seek a mate in another territory.

In contrast, most of the dominant female’s sons never leave home. They assist with breeding tasks - provisioning of nestlings and young birds, defence of nests - but do not mate with their mother.

However, they actively court females on other territories and on occasion these result in extra-group matings - the same adulterous activity that their mother engages in back on their home territory.

Our forest is home to several families of superb fairy-wrens. Every spring we see males flaunting their fresh, bright-blue nuptial plumage. And occasionally we get to see the successful outcome of these breeding displays.

An early post-fire breeding attempt

Fairy-wrens reappeared very soon after the January 2020 fire which razed our forest. In October of that same year, a female built a nest in the tangled branches of a fire-killed tea-tree bush close to the northern wall of our house.

A pair of males was seen hanging around the female at this time. One of these males is likely to be the dominant male of the family group. Neither helped out with nest construction. As a rule, the dominant female builds her nest alone (Cockburn et al., 2003).

By early November the female had apparently completed her nest and laid a clutch of eggs. These had hatched and there were now hungry mouths to feed.

The males were now put to work helping the female satisfy the appetites of the nestlings. They captured a variety of insects and spiders in the surrounding undergrowth and bushes and ferried them to the nest site. They would often use a nearby tree stump as a landing post before flying into the nest bush with their prey.

Feeding of the nestlings was proceeding smoothly. Then one day a pied currawong, which had been taking a considerable interest in proceedings from nearby perches, apparently decided that the nestlings were now large enough to make a decent meal for its chicks.

Two or three swoops down to the tea-tree bush and all of the hard work of the fairy-wrens was undone.

That’s a frequent occurrence – around a half of superb fairy-wren nesting attempts fail due to predation (Backhouse et al., 2023). To compensate, females make repeated attempts to nest (up to 8 times!) in a single season.

Another nesting attempt - hidden in plain sight

This summer we were treated to a particularly close-up view of the feeding and care of superb fairy-wren nestlings.

These birds occupy the same territory - the area surrounding our house - as the group featured above. The dominant male and female pair is likely the same as that present in 2020, but we can’t be sure as we don’t carry out bird ringing.

The resident breeding female was sufficiently discreet with her nest building that its presence only became evident after we noticed the parents feeding nestlings - on 7th January this year. When feeding actually began is unclear as we had been away from home for 3 days before that date. The feeding period for this species is reported to be 10-14 days (Beruldsen, 2003) .

While the nest was hidden, its position (indicated by a vertical arrow in the photo below) was clearly shown by the activity of the feeding birds. I could only guess how many chicks were in the nest. (Spoiler alert - a count at fledging showed there were 3, as is usual for this species).

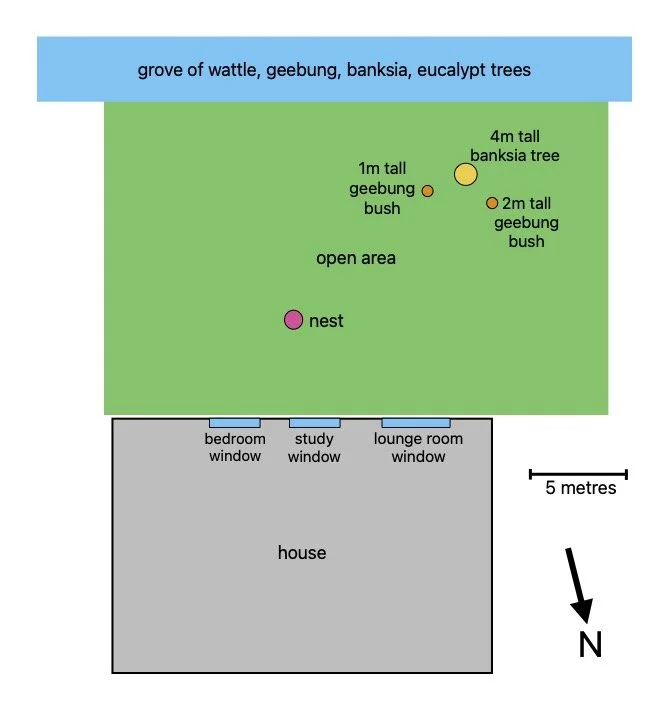

The nest lies in an open part of the forest adjacent to the southern wall of our house.

This 15x20m area is covered by dense undergrowth with a diverse mix of grasses, sedges, forbs and low shrubs - none taller than 80cm.

The only middle storey plants present here are a single 4m tall Old-man Banksia (Banksia serrata) tree and a couple of 1-2m high Narrow-leaved Geebung (Persoonia linearis) bushes.

view of the nest site through our study window

The southern boundary of the open area is marked by a dense grove of 2-3m tall Sunshine Wattle (Acacia terminalis) and Sydney Golden Wattle (Acacia longifolia) trees, eucalypt saplings, and Narrow-leaved Geebung (Persoonia linearis) bushes.

Interspersed amongst this middle storey are four mature 30m tall eucalypts.

plan of fairy-wren nesting site

The nest lies towards the northern boundary of the open area, in a patch of prickly Common Heath (Epacris impressa) - indicated by the vertical arrow in the photo alongside.

A tall, spindly Slender Riceflower bush (Pimelea linifolia) - see horizontal arrow here and in the photo above - lies 50cm away.

The feeding birds often landed in this shrub before diving down to the nest to feed the nestlings.

close up view of nest site, looking towards the southern wall of our house

This behaviour and the close proximity of the nest to our study window (just 4m away) made it relatively easy to view the birds and their insect prey. The house functioned as a perfect hide! I was therefore able to collect data on the following aspects of feeding behaviour:

how many adult birds were involved

the type of food delivered

the frequency of food delivery

how the adults approach and leave the nest during food delivery

and ultimately, the success of their breeding efforts

This nest has only two providers

I followed the feeding of the nestlings from 9th January, through to the day of fledging on 17th January.

I am confident that only two birds - a male and a female - were feeding the nestlings. This is based on a comparison between individual birds of wing feather colouration (for the male) and the pattern of feather bases around the eye (for the female, arrowed in photo below).

I never saw more than two birds - a male and a female - coming to the nest at the same time. Indeed, it was rare to see more than one bird arriving at the nest at a given time. This supports my conclusion that the nestlings had only two provisioners.

Two other males are regularly seen in the same territory as the feeding birds. However I never saw any evidence that either was helping with feeding or protection of the nestlings.

This differs from the breeding behaviour in the same territory in spring 2020 when two males assisted the female with feeding and both were often sighted together near the nest with prey.

Prey selection

The adults captured a wide range of prey for their nestlings. Identifiable insects include: lepidopteran larvae (n=6); adult butterflies (all Imperial Hairstreak, n=13); flies or fly larvae (n=8); cicadas (n=23); katydids (n=5); ant eggs (n=4) and beetle larvae or adults (n=4).

It seems that the adults hunt opportunistically - grab anything around at the time that is palatable, easy to find, easy to capture, small enough to fit in the mouths of your nestlings and yet large enough to satisfy their hunger.

The two most common prey items - cicadas and the Imperial Hairstreak butterfly (Jalmenus evagoras) - were frequently seen in the fairy-wrens’ territory at the time of nesting.

Cicadas were eclosing in numbers at this time and would have been easy prey soon after they emerged. Indeed, some of the cicadas delivered to the nestlings had clearly just recently eclosed as their wings had not inflated fully.

Jalmenus evagoras has bred intensively in the area around our house this spring/summer. The foliage of Black Wattle (Acacia mearnsii) is a favoured food plant for Jalmenus caterpillars - here is a post we did on this interaction some years ago. The caterpillars get protection from potential predators and parasites because of a mutualistic association with ants, which swarm around the caterpillars to take the honeydew they secrete.

When female pupae are about to emerge as adults, they emit a pheromone which attracts adult male butterflies. Mating takes place as soon as the adult female ecloses from her pupal case. As a result, a black wattle bush is often covered in a frenzied cluster of adult male butterflies.

The above panel of photos shows a group of Jalmenus pupae on the lower part of the black wattle branch, covered in attendant ants. Higher up, an adult female which has just eclosed can be seen copulating with a male. Other males are flying in to get a piece of the action.

As the female butterflies eclose, they are likely to be easy picking for the birds. The same probably applies to the male butterflies whose attention is focussed on the eclosing females, rather than avoidance of the fairy-wrens.

So it comes as no surprise that this butterfly is a large component of the fairy-wren nestlings’ food.

Frequency of food delivery

Delivery of food to the nestlings began soon after dawn. We often woke to the twittering of the adults and nestlings, as our bedroom window is close to the nest. Feeding continued, with periods of inactivity, throughout the day until late afternoon on some days.

On several days I made uninterrupted observations for an hour or more. As one would expect, the interval between food deliveries was highly variable – sometimes as short as 1-2 minutes, although a 6-10 minute wait between feeds was more usual. Bear in mind that only one of the 3 nestlings gets fed when an adult arrives with prey.

On the four days leading up to fledging I saw 16, 17, 12 and 17 feeding events respectively. As I was not monitoring continuously all day, feeding would have been more frequent than this.

As well as providing food, the adults dealt with the other end of the feeding process. They were frequently seen flying out of the nest with a faecal sac, the common method used by passerine birds for removing the faeces of their nestlings.

Approach to and departure from the nest

The optimal site for a nest?

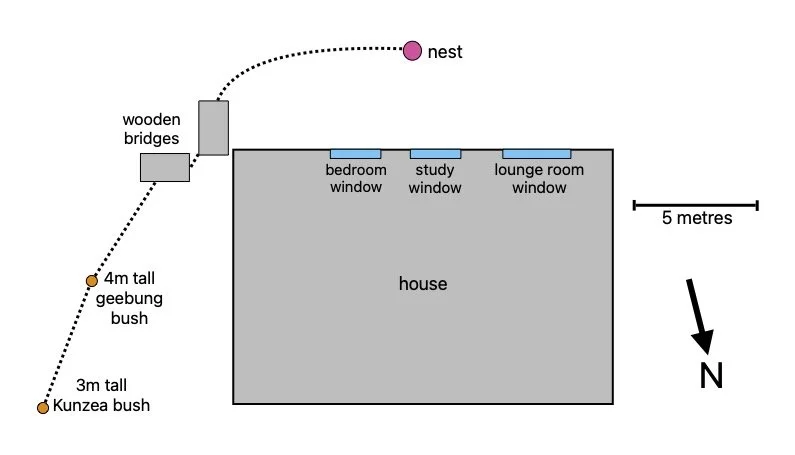

Here is the plan I showed earlier of the fairy-wren nesting area.

The location of the nest in a wide, open area would seem to carry the risk of a predator noticing the adults delivering food to the nest.

Findings elsewhere however, indicate that a dense middle storey increases the level of predation, probably because it provides hiding places for predators (Backhouse et al, 2023).

So on this count perhaps the open area isn’t such a bad choice for a nest.

In any event, the adults would want to make the feeding of the fledglings as rapid and covert as possible. Recall that around a half of superb fairy-wren nesting attempts fail because of predation.

fairy-wren nesting area plan

Where to hunt for baby food?

With its dense and varied ground cover, the open area would appear to be a good hunting ground. The vigorous growth of vegetation in this area following heavy rainfall in the late spring/early summer had boosted insect numbers. Indeed, fairy-wrens are often seen feeding here at other times.

So it comes as a surprise that the provisioning birds were seldom seen hunting in the open area around the nest. Perhaps because this activity would attract predator attention of passing predators, such as pied currawongs.

Instead, the parents hunted in other areas of their territory - on other sides of the house or downhill, to the west of the open, nesting area…in and around the Jalmenus colony.

Making prey delivery discreet

At times the female would make a sudden appearance, flying directly into the nesting bush with her prey. She delivered the food and departed rapidly. So quickly, in fact, that I was unable to get a photo of this type of approach.

But often both she and the male showed a different approach. They flew with their prey either into the dense vegetation on the southern border of the open area or into the tall banksia tree or Persoonia bushes within the area.

They perched there for some time - for a minute or two in some cases - before flying rapidly to the nest site. I presume they were checking the area for predators.

A surprising pause before prey delivery

Then, rather than flying directly into the nest bush, they would fly into the tall Pimelea immediately adjacent to that bush. They would perch there for some time before making a quick dive down to the nest.

In this panel of photos, the female flies into the Pimelea and waits there for 13 seconds before flying down to the nest.

The same behaviour can be seen in the following photos and video of the male. On occasion he would wait in the Pimelea bush for up to 2 minutes before flying down to the nestlings.

The exit is also paused

After making their food delivery, both the male and the female generally flew back into the same Pimelea bush. They often remained there for some time - up to 4-5 minutes - before making a final, quick exit from the bush and the open area.

So why do they sit in this open, twiggy bush right alongside the nest? Surely this would risk attracting the very attention they otherwise appear to be at pains to avoid. Indeed with their loud singing from this perch they seem to be advertising their presence. Curious.

Dénouement - fledging

Soon after dawn on 17th January, we heard much chattering at the nest. So I quickly took up my perch nearby to record the action.

Between 5:47 and 6:02 both parents repeatedly flew into the Pimelea bush, spending 30-40 seconds there at a time. Twice the male brought in prey.

Just before 6:00, I spied a chick in the nest bush outside of its nest - fledging had begun!

Then, just a couple of minutes later, at 6:03, I saw the fledglings leaving the nest bush. You can see them moving around in the video below. The female flew frantically back and forth around the bush and into and out of the Pimelea, supervising their departure.

Three minutes later, at 6:06, I spotted them hopping along the wooden bridges that run between the open area and the eastern side of the house. Their mother appeared to be guiding them.

path of fledglings from nest to roosting locations

By 6:37 the chicks had found their way to a nearby Persoonia bush, where they perched 1.3m above the ground. Both parents were feeding them but encouraging them to move them away from this exposed position - as seen in the following videos. They remained on this branch for the next 4 minutes.

By 6:48 the chicks had moved to a large Kunzea bush 8m away, which afforded better protection. They were being supervised and fed here by both parents.

At 7:57 the chicks were still in the same bush, but by 9:41 they had moved out of it into the dense undergrowth to the north. The male parent flew up a nearby tall dead wattle tree to watch out for potential threats. The chicks are very vulnerable at this stage.

A heavy downpour of 30mm of rain in an hour late that night left us concerned for the fate of the fledglings.

However, a week later we spotted all three of them safe and sound in a large Persoonia bush. Their tails had grown noticeably in that time.

Now that the chicks had fledged, I took the opportunity to examine their nest. It had been built just above ground level, wedged between branches of the prickly Epacris bush. It must have been a tight fit for the babies!

Growing up fast

It’s now almost 4 weeks since the babies fledged. I’m happy to report that all three of them are alive and well.

We see them every day actively foraging in the undergrowth and shrubs around the house. They seem to be doing laps of the house!

They’ve already developed to the point where it’s difficult to tell them apart from their mother - who appears to accompany them as they roam around their territory.

This first panel shows a bird, which I believe is the adult female, based on the blue-grey tinges in the tail. She has caught an insect larva here and will probably deliver it to one of the fledglings. She is definitely still feeding them.

This second panel shows fledglings. Their tail has only grey feathers and their eye ring does not extend as far back as in the adult female.

We regularly see two of the chicks in the company of the adult female, often begging for food. It will be a while before they hunt well enough to keep themselves fed.

The third chick is being cared for by an adult male - either the dominant male or one of the two helpers we’ve seen in the group. The adult is starting to lose his nuptial plumage, now that mating season is over.

References:

Backhouse, F., Osmond, H.L., Doran, B., Stein, J., Kruuk, L. E.B. & Cockburn, A. 2023. “Population decline reduces cooperative breeding in a spatially heterogenous population of superb fairy-wrens”. (preprint - https://ecoevorxiv.org/repository/object/5344/download/10513/)

Beruldsen, G. 2003. “Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs”. Kenmore Hills, Queensland.

Cockburn, A., Osmond, H.L., Mulder, R.A., Green, D.J. & Double, M.C. 2003. “Divorce, dispersal and incest avoidance in the cooperatively breeding superb fairy-wren Malurus cyaneus”. Journal of Animal Ecology, 72 (2): 189-202. (free access https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00694.x)

Dunn, P.O. & Cockburn, A. 1999 “Extrapair mate choice and honest signalling in cooperatively breeding superb fairy-wrens”. Evolution 53 (3): 938-946