15th January, 2024

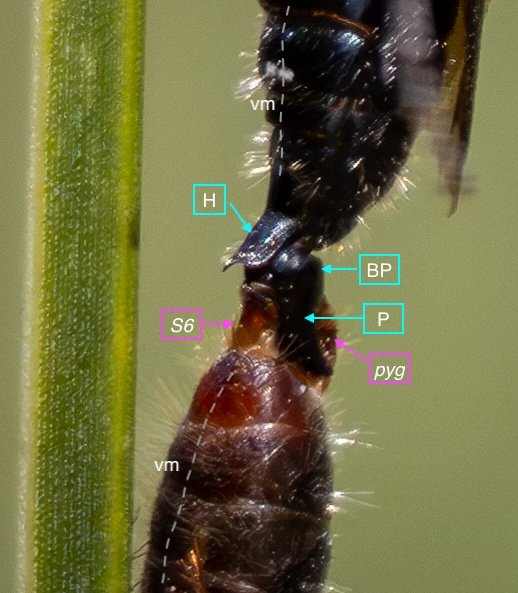

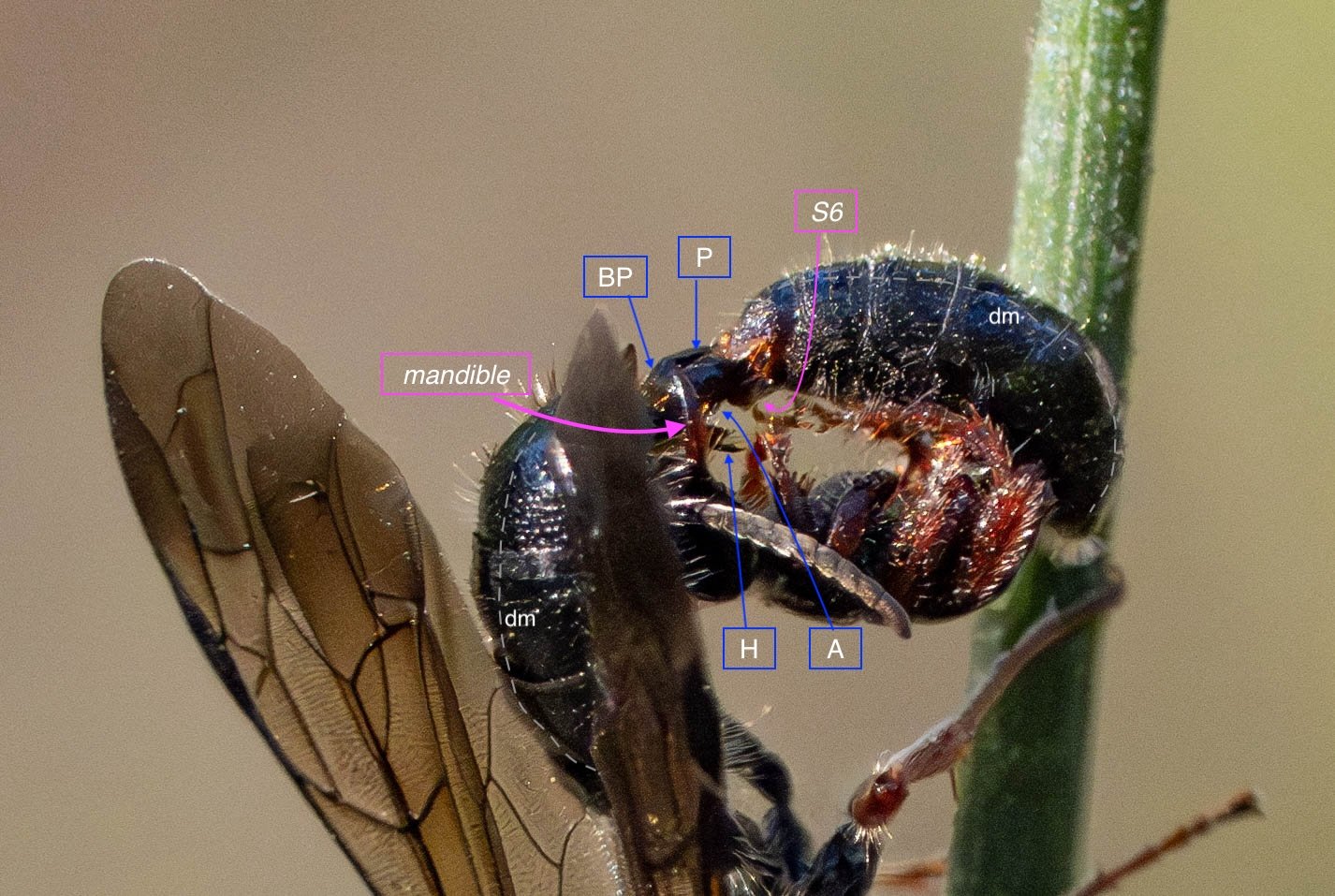

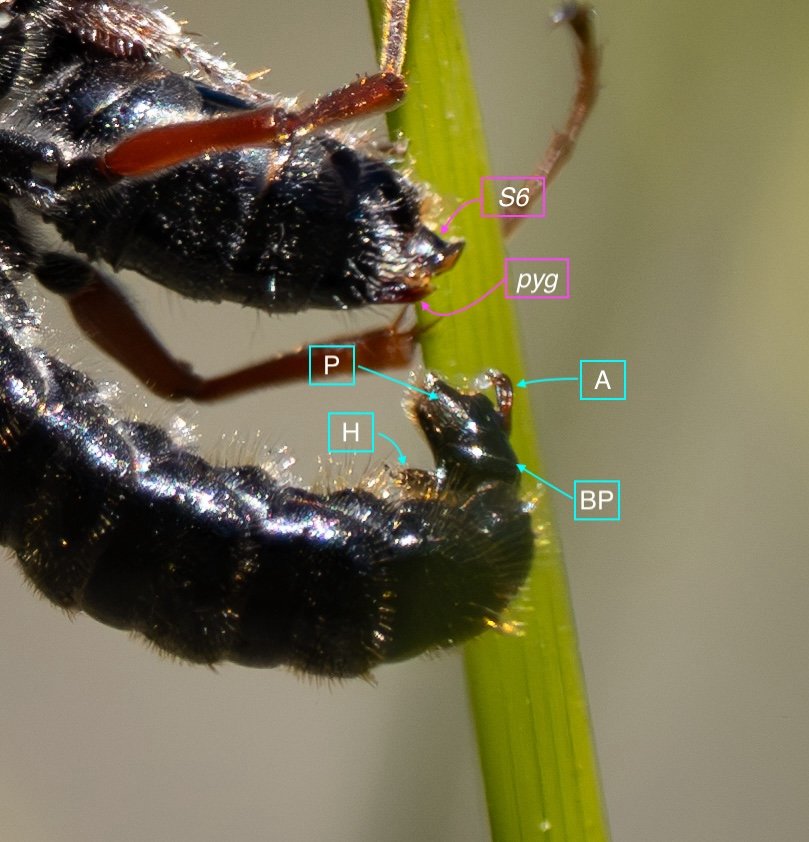

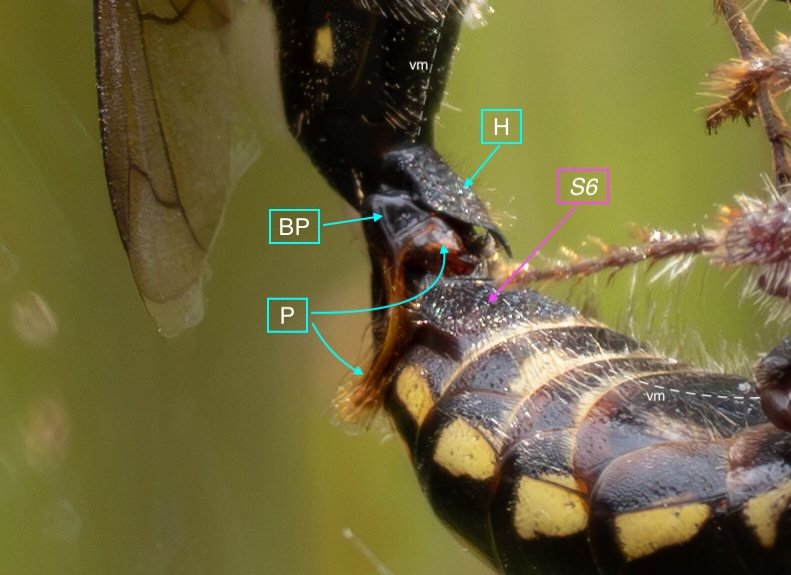

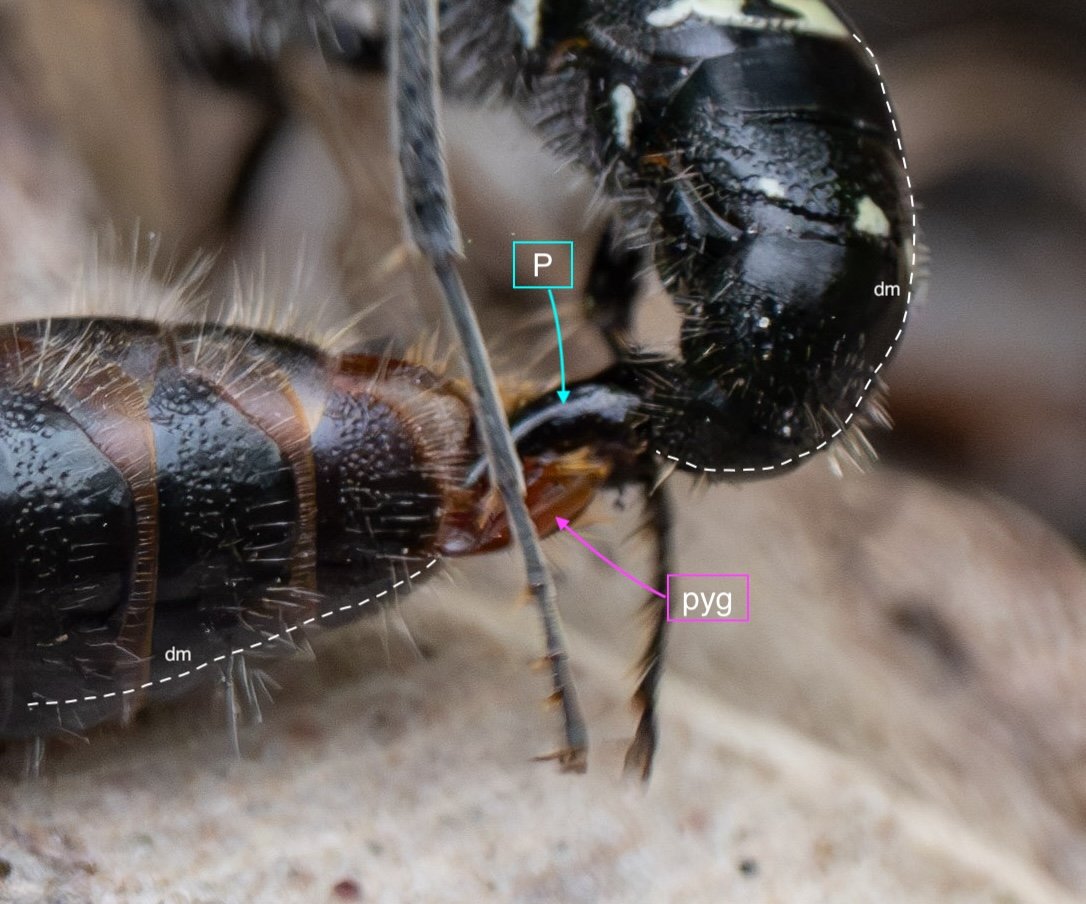

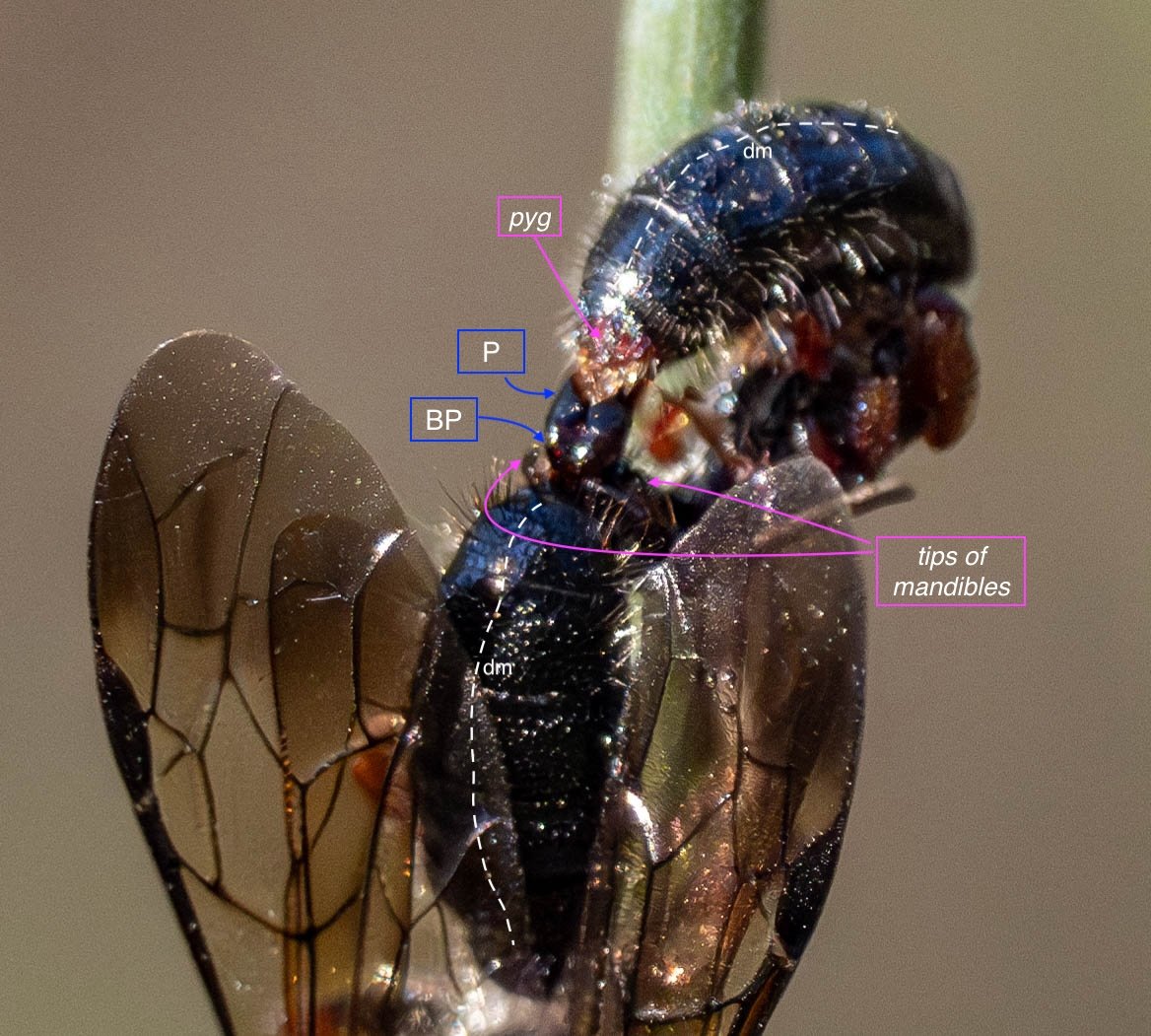

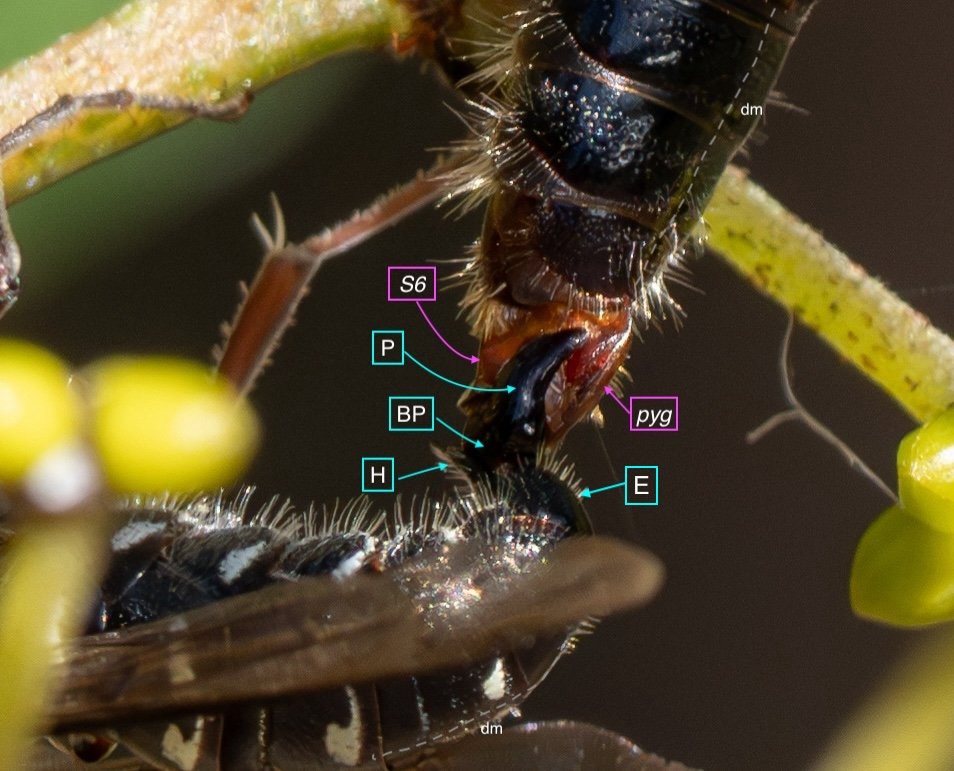

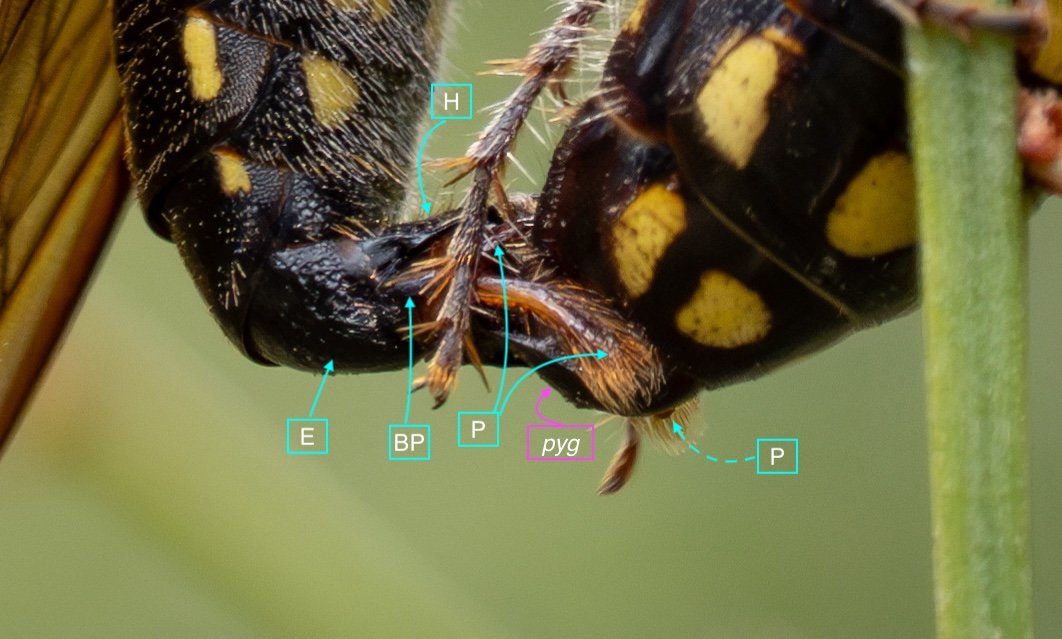

Phallus inverted. “The parameres are the main grasping organs and as such their apical margins are shaped to fit against the apex of the female metasoma.” (Brown, 2000. p. 213)

Phallus inverted. Several features in this image are likely to be helpful in genus ID: the shape of the parameres, including the longitudinal ridge; the transverse sculpting on the basiparameres; and the apical lip on S6 of the female.

21st January, 2023

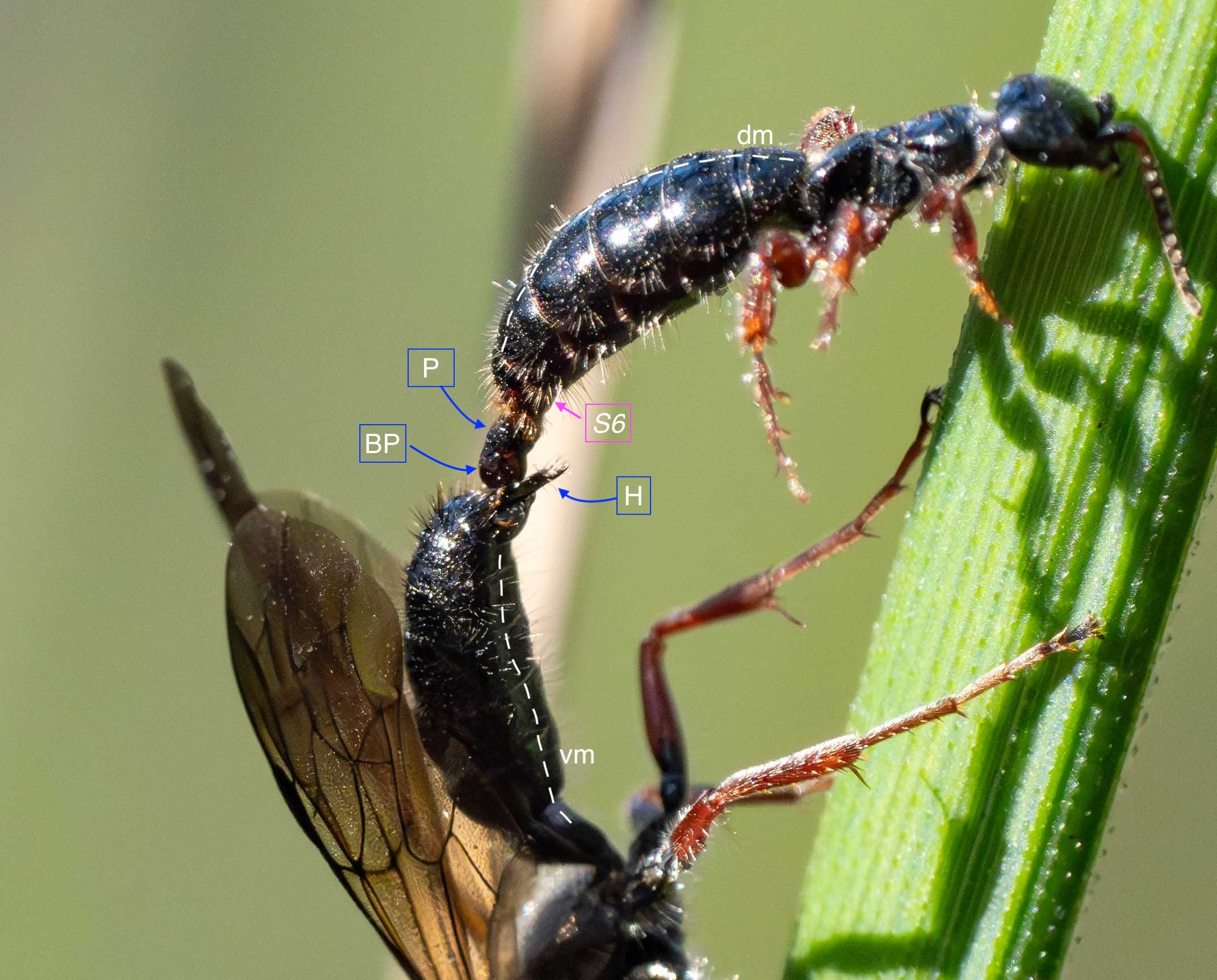

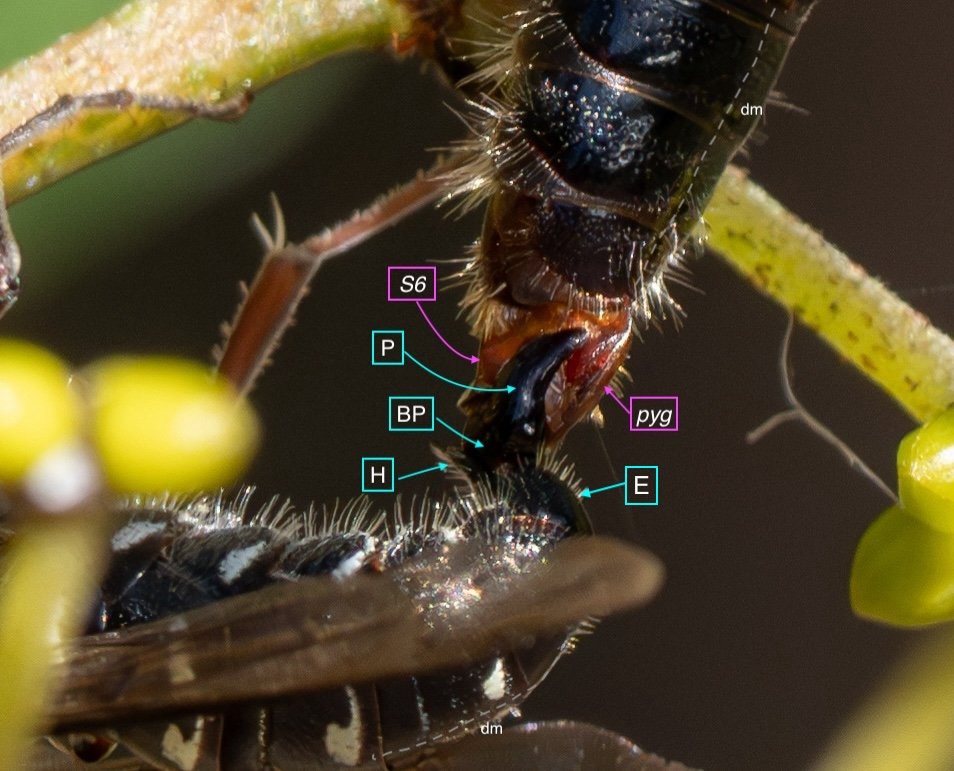

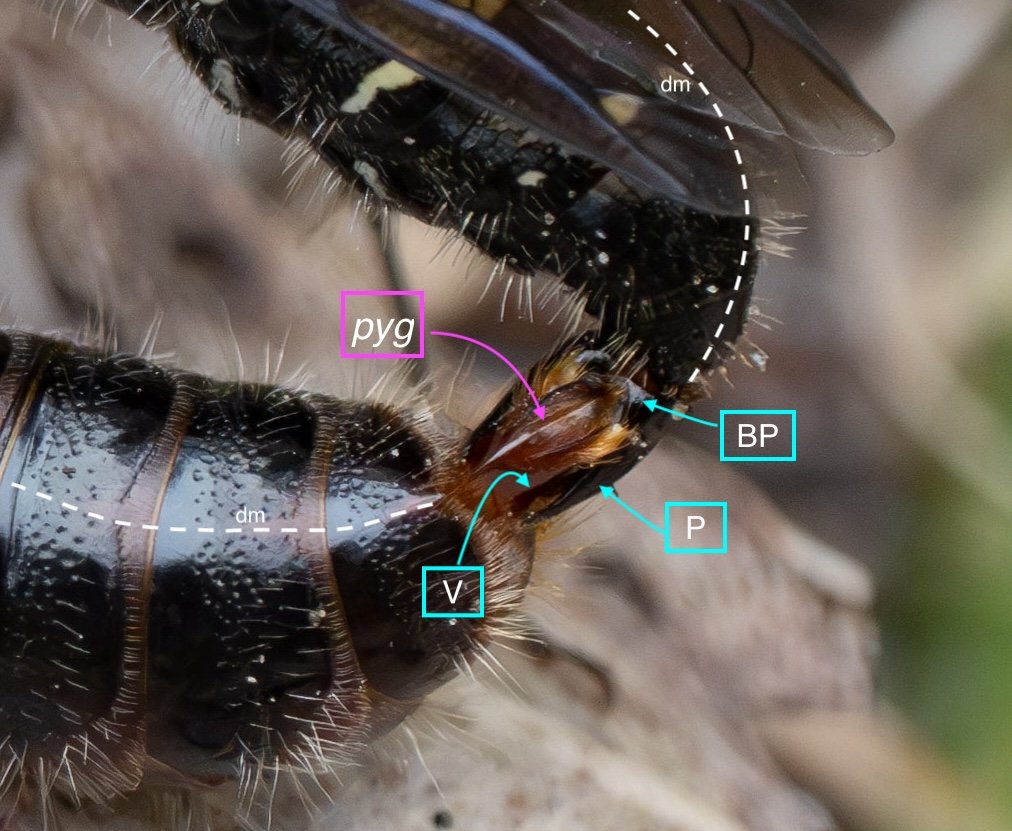

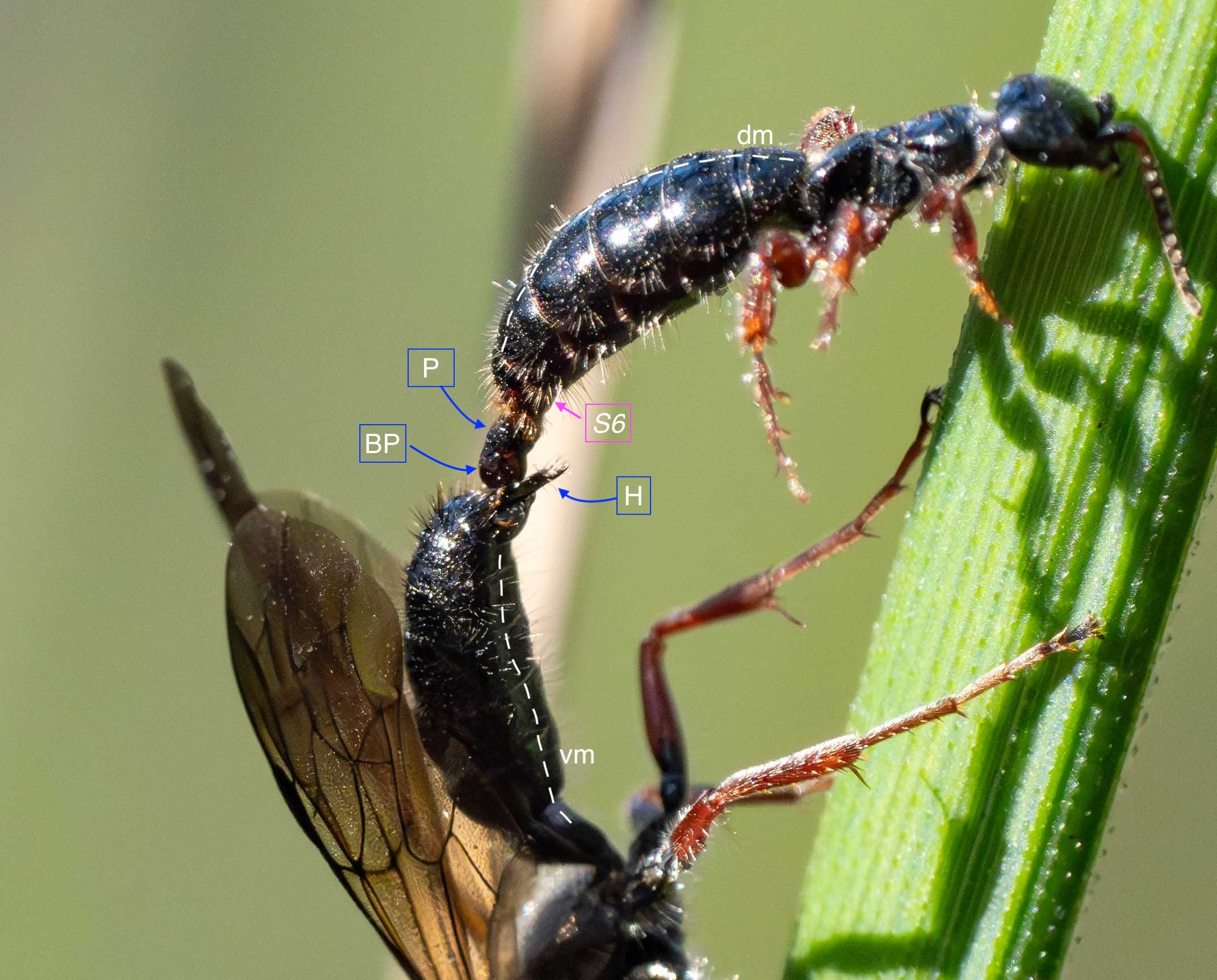

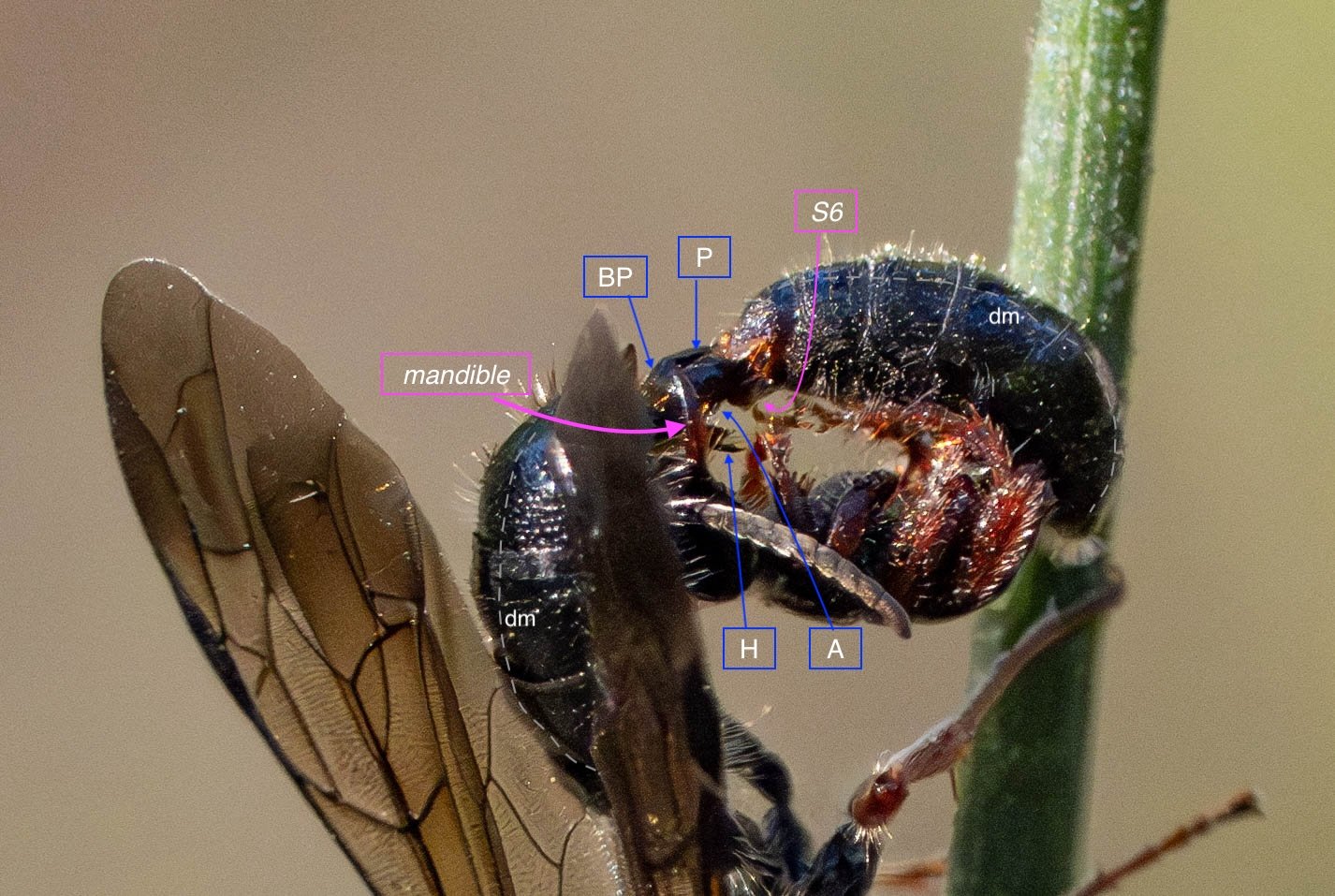

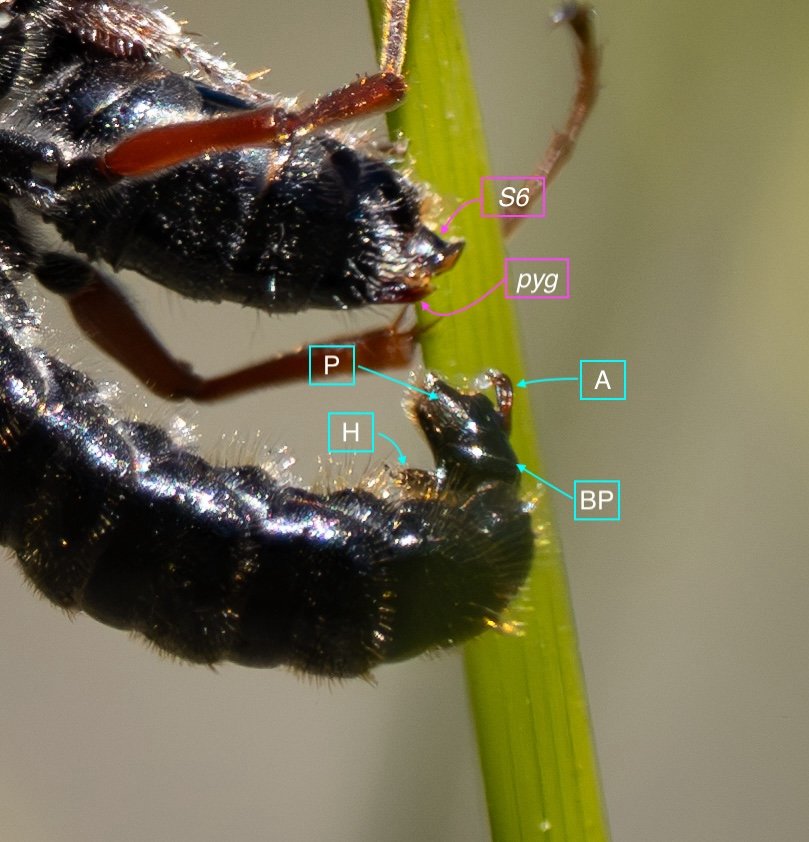

Phallus inverted, and thoroughly exserted! The basiparameres are well clear of the genital cavity, perhaps in part due to the weight of the suspended female. Yet the coupling remains secure.

16th February, 2023

Phallus inverted. The male looks very much like the male in Example 5. A close comparison of the genitalia … and I’m further convinced. The smooth, curved parameres and the narrow, ridged pygidium. Looks a match to me!

22nd February, 2024

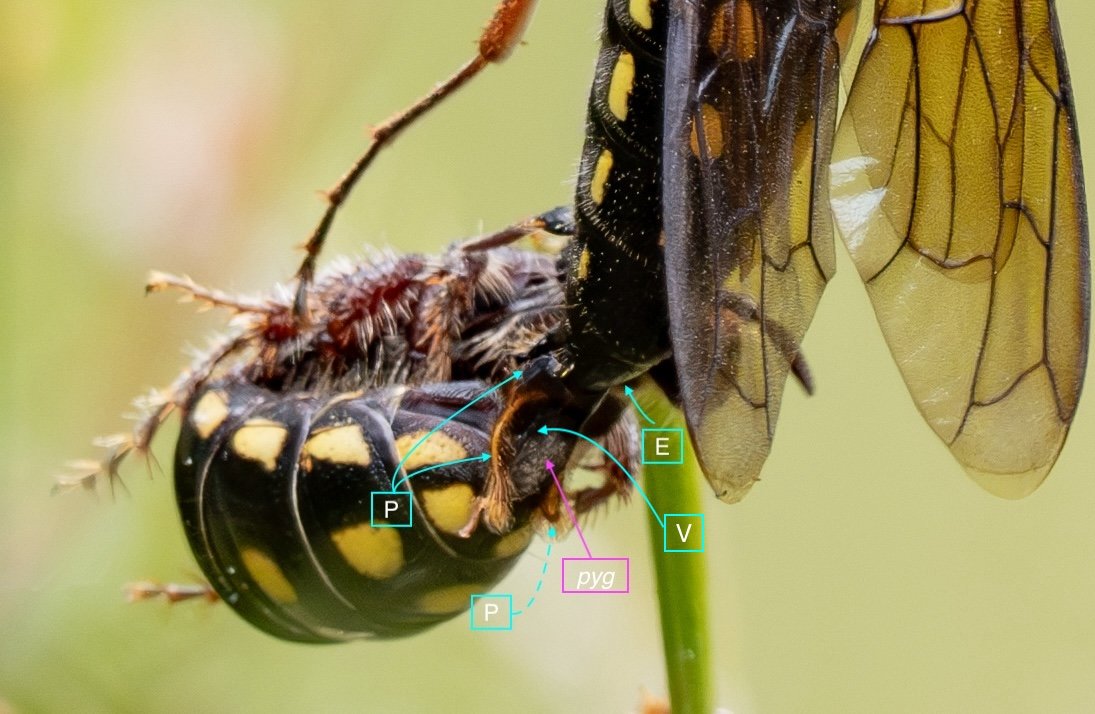

Short, squat parameres and an indistinct pygidium. I have many sightings of lone males of this species, but few couples. I’m now keen to see if I can ID it … the shape of the terminalia should help.

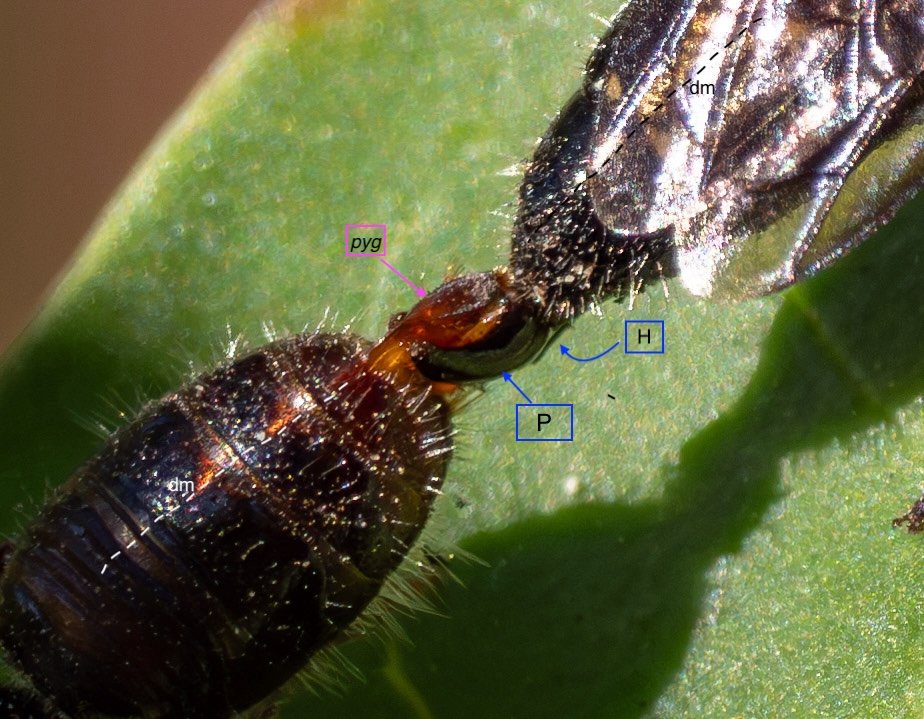

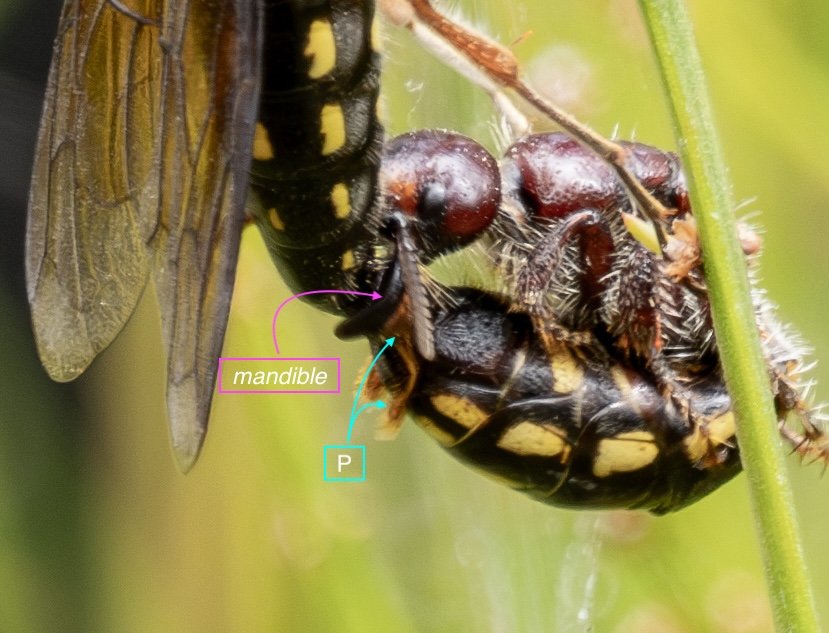

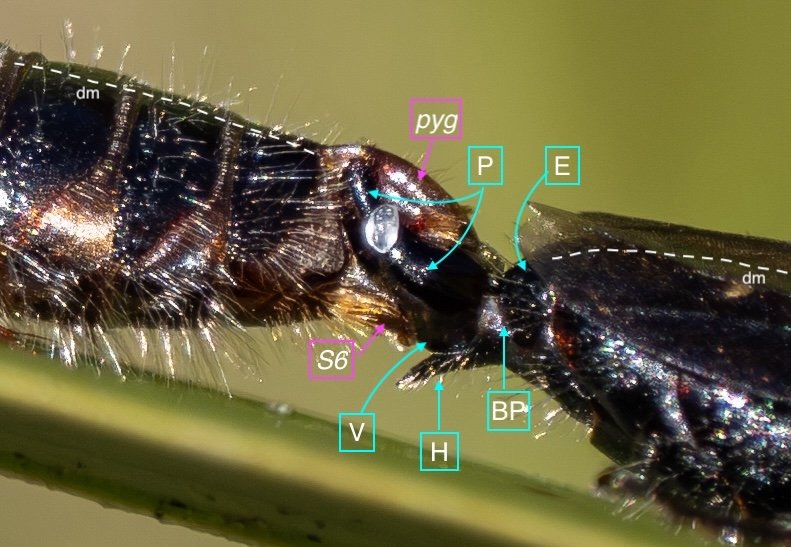

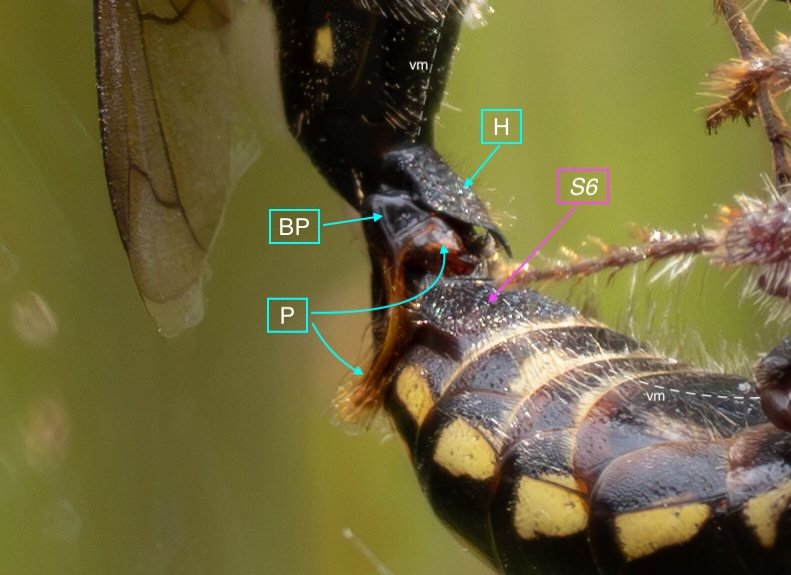

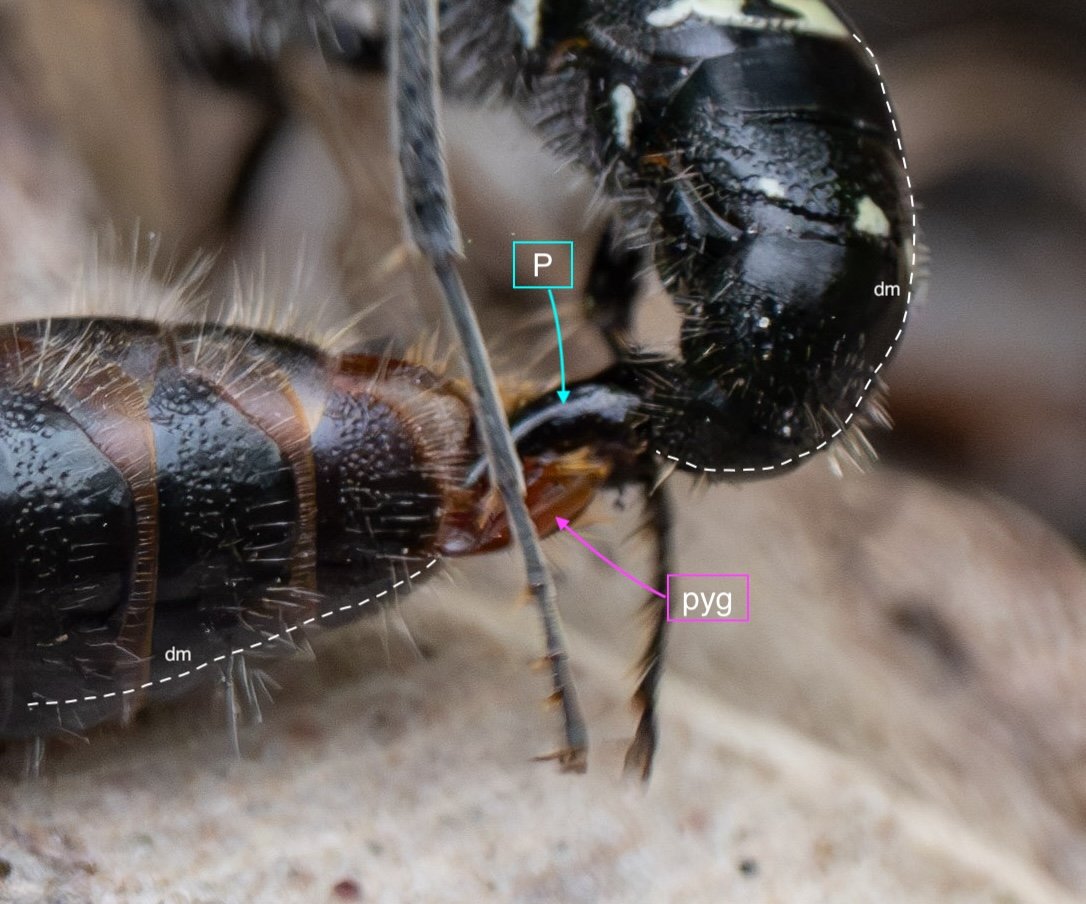

The bite. It has been suggested that by biting at the terminal abdominal segments, she assists in the transfer of sperm (Ridsdill Smith, 1970). Or perhaps the firm grip on the basiparameres simply helps to support her in this compact, carrying position.

The bite. Note the long mandibles of the female wrapped around the basiparameres of the male. The phallus is strongly exserted and the aedeagus is visible … suggesting the female may be pulling clear of the coupling.

He was seeking to feed her by regurgitating drops of liquid onto the leaf, then walking forward to position her over it.

But she didn’t seem interested, maintaining her manibular hold on his basiparameres. In defeat, he would back up and consume the drop himself. No waste.

I watched this pair for more than 10 minutes as they moved about in a small area, adopting different postures and affording me a good look at their coupling apparatus. Just seconds after this shot they separated. She dropped to the forest floor and quickly disappeared from view.

24th March, 2023

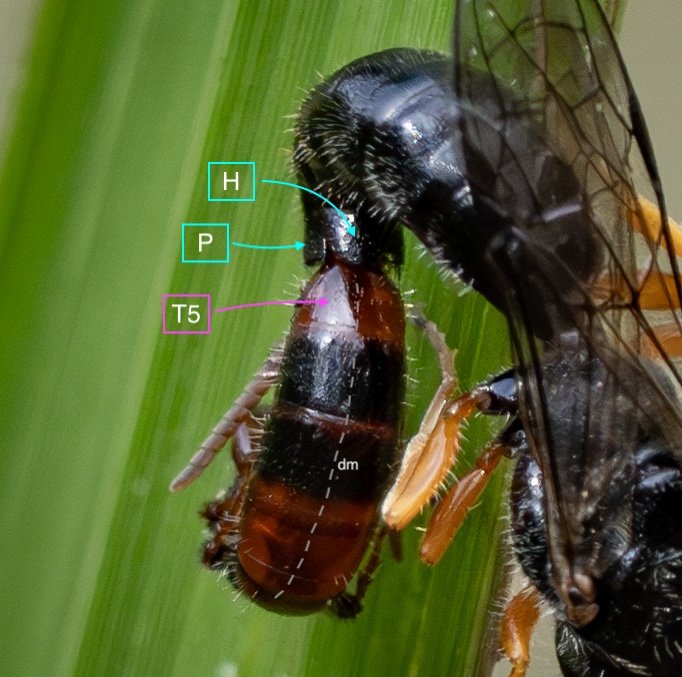

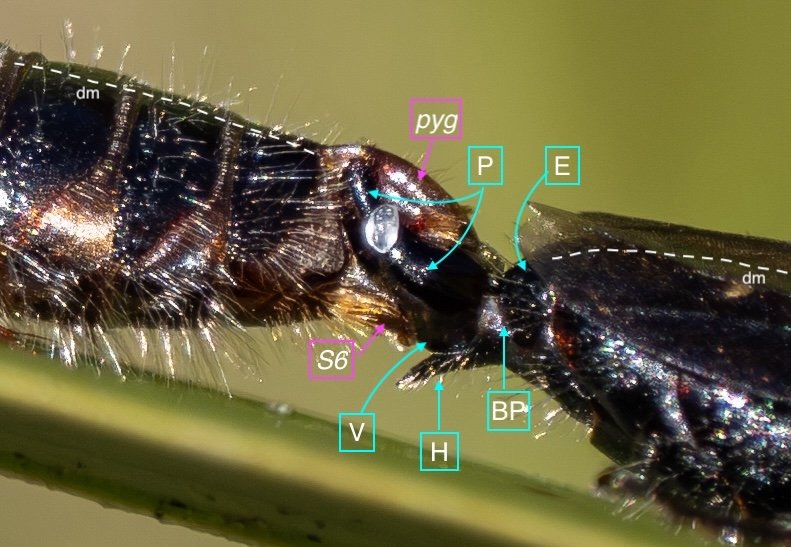

The terminalia of the male enclose the end of the female’s abdomen. Given’s (1958) characterisation of Eirone states:

“The male may be separated from other members of the rhagigasterine genera by the unspecialized hypopygium, which is apically broadly rounded and rarely projects beyond the epipygium.” (p. 321).

That fits!

The epipygium is simple, evenly rounded apically, and lacking obvious ridges … consistent with Eirone (Brown, 2000).

Parameres short and wide.

Notably, the female remains in the ‘Step 1’ orientation. No twist!

18th April, 2023

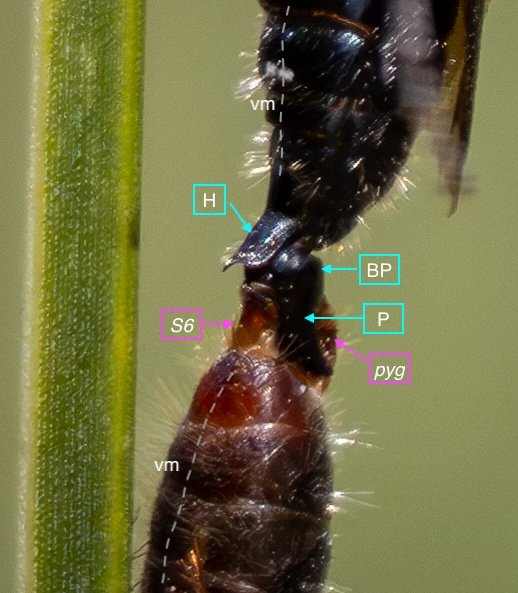

Phallus inverted. The apical edge of S6 in the female has a lip. This is a feature of some genera, “so that it can be … butted against by the apex of the basiparameres ventrally (when inverted)”. (Brown, 2000, p. 215).

Phallus partially inverted. Actually, partially ‘reverted’, as this shot was taken after full inversion. As the pair clambered around the vegetation, the phallus twisted to accommodate the independent movement of the female. Note also the distinctive shape of the pygidium, with a Y-shaped carina. This is likely to be helpful for genus ID.

Phallus inverted. The parameres securely grip the female terminalia, yet the male is still able to flex his body in the dorso-ventral axis – note that the epipygium is extended, bending the tip of his body ventrally, yet the parameres are angled dorsally. This is due to the ball and socket joint of the phallus.

28th August, 2022

The bite. Phallus in natural orientation. He landed briefly landed on a leaf before flying off … all the while with her gripping his terminalia in her mouthparts. Both are covered in pollen, so perhaps they had been feeding at flowers.

25th October, 2023

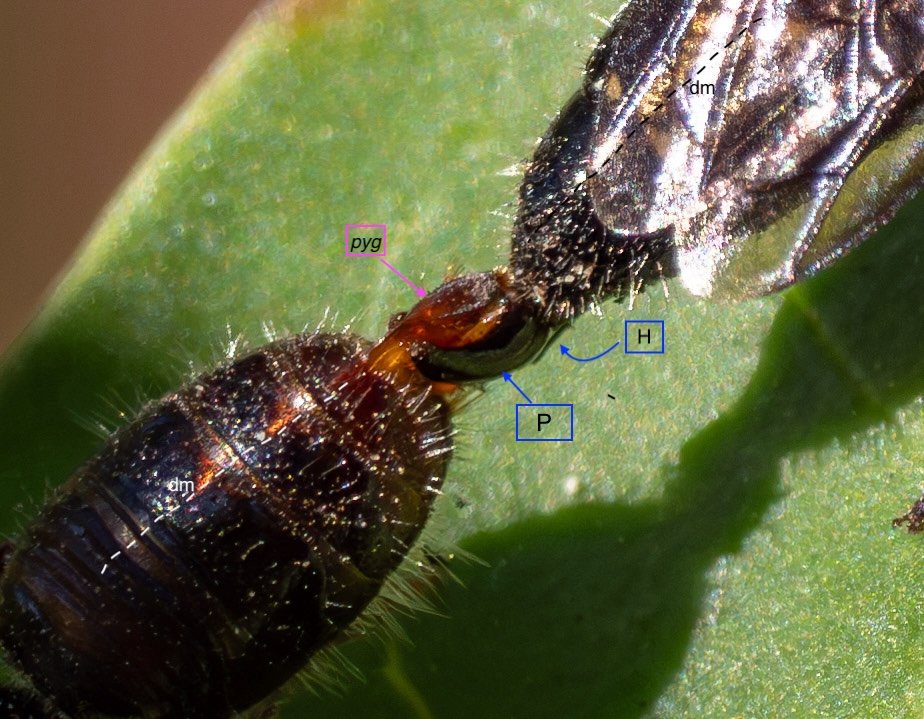

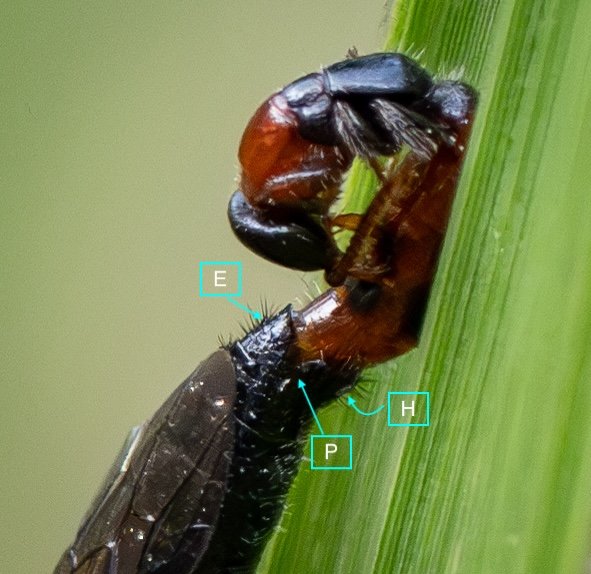

Phallus fully exserted, but still in natural orientation (‘Step 1’ of earlier diagrams). Note the relatively short parameres (cf. Example 1). Also note the projecting aedeagus and the open terminalia of the female.

Coupling involves the male arching his body ventrally, probing with his exserted phallus. At this stage the volsellae (not visible here) are probably at work, separating the female sclerites.

This image has me confused. The structure that I’ve labelled H certainly looks like the hypopygium … but if it is, it has been pushed into a more dorsal position. Puzzling.

The twist. The female is now mid-twist, causing the phallus to invert as she moves into the typical venter-to-venter arrangement of a coupled pair.

Now securely coupled, he took flight just seconds later.

22nd November, 2022

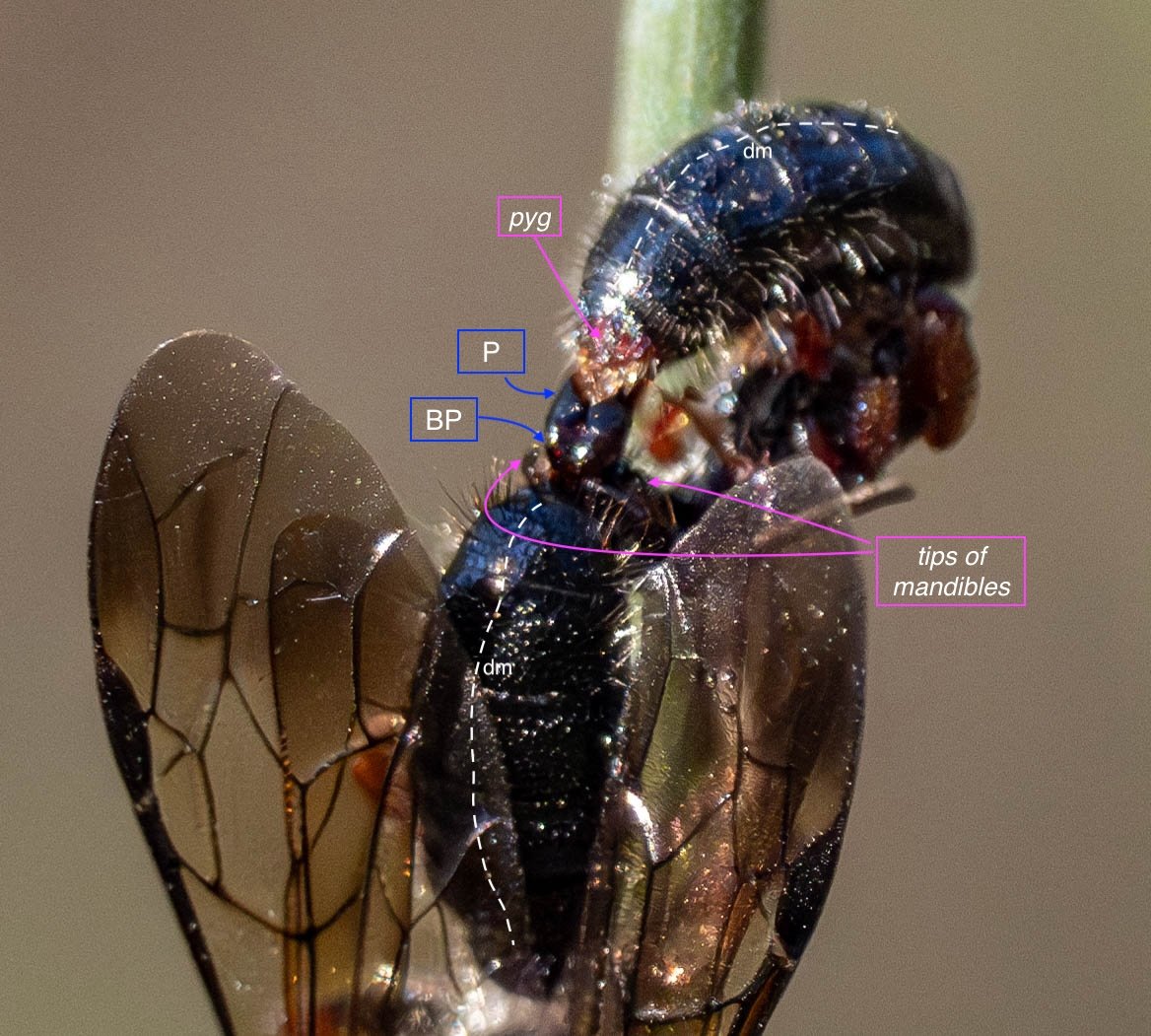

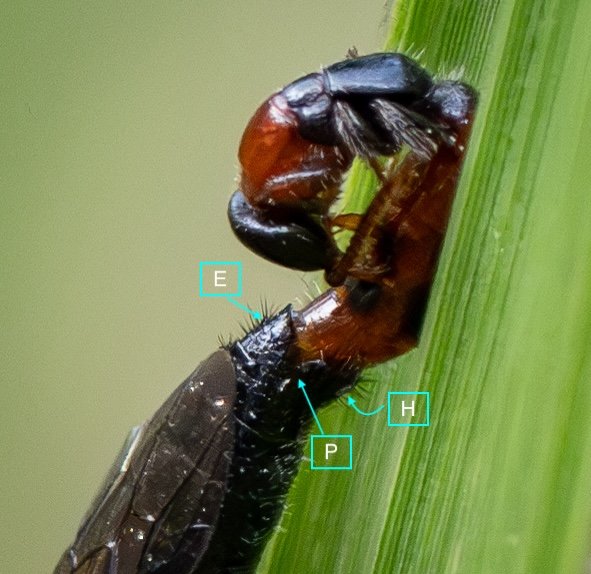

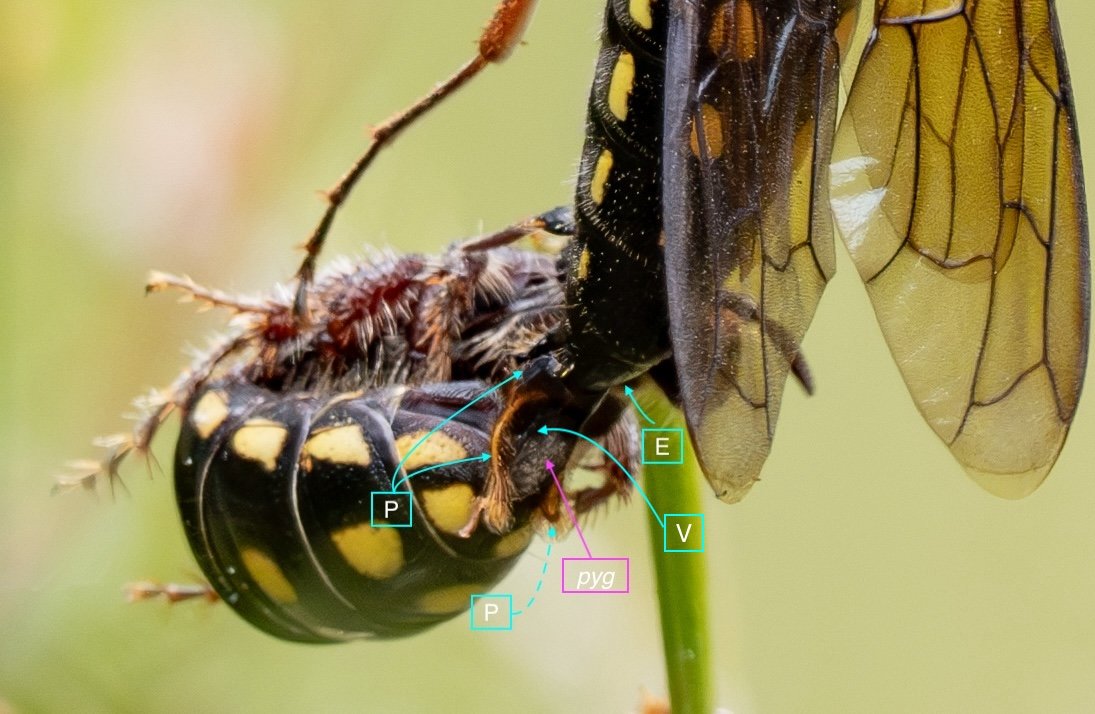

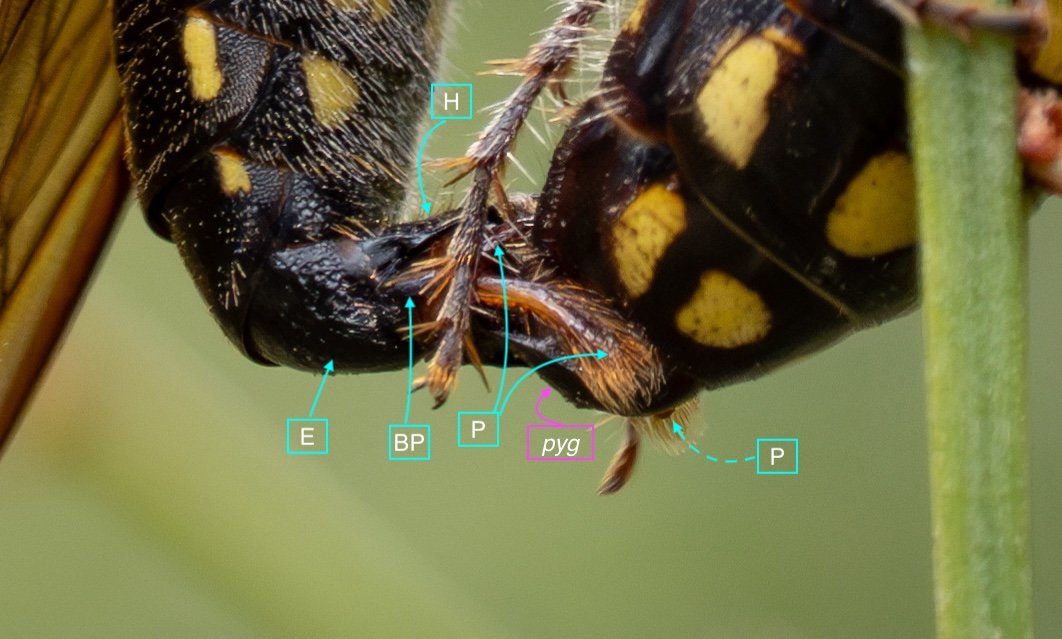

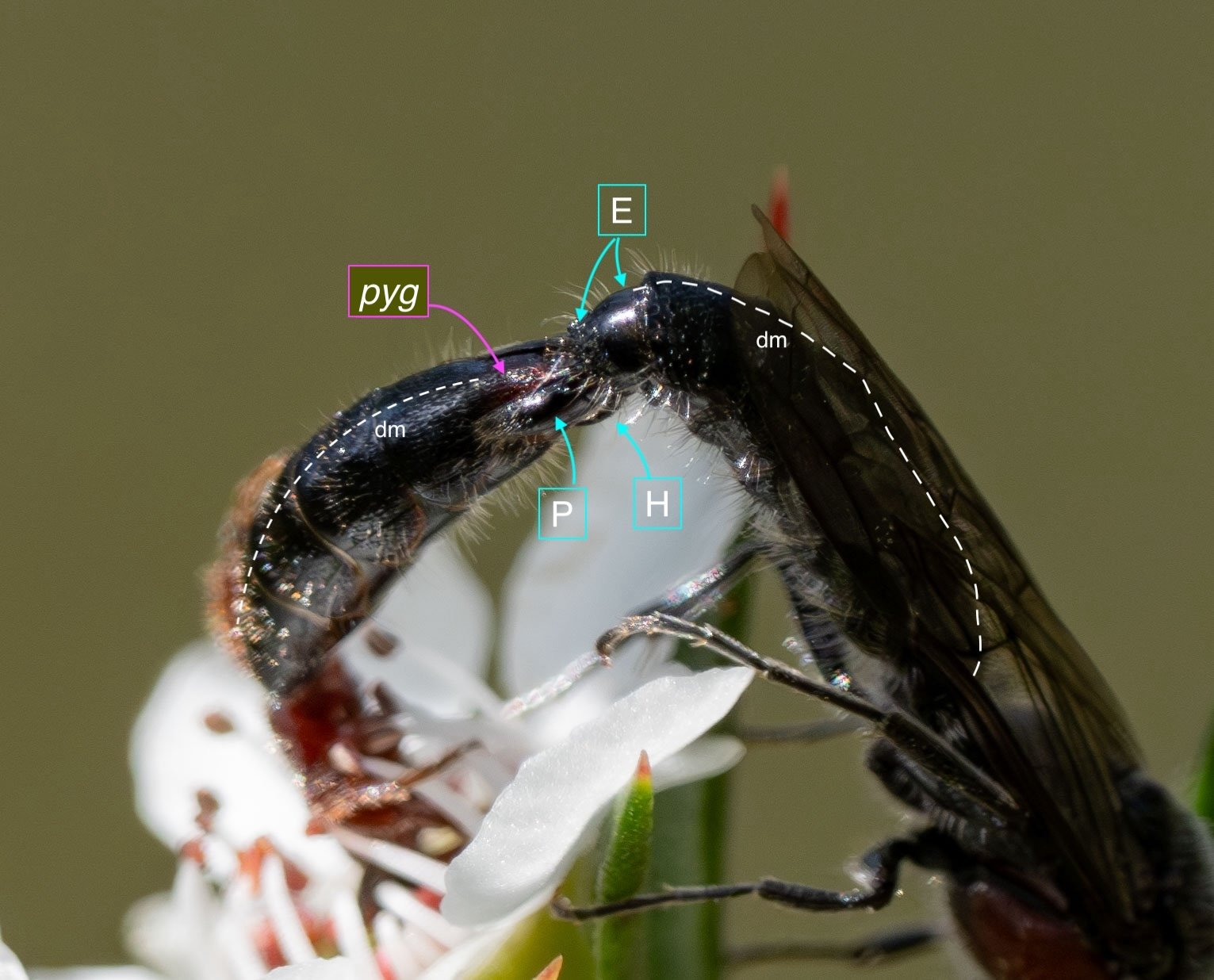

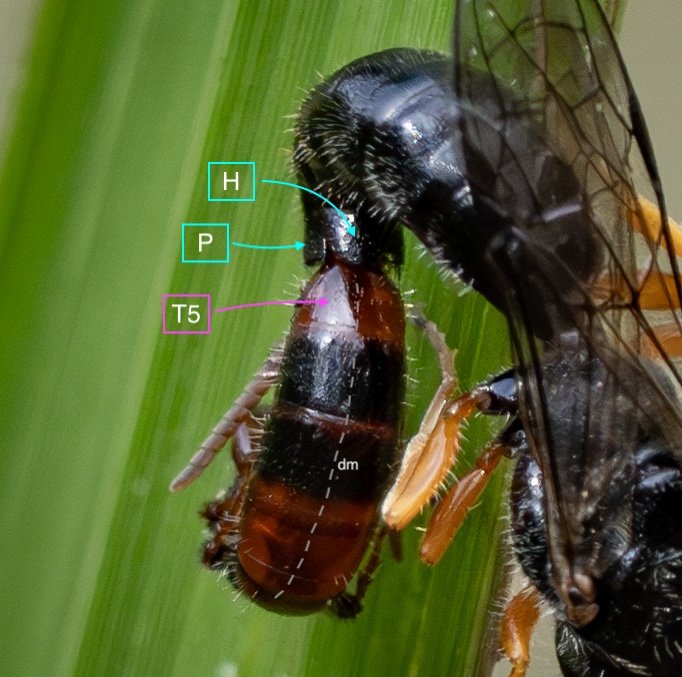

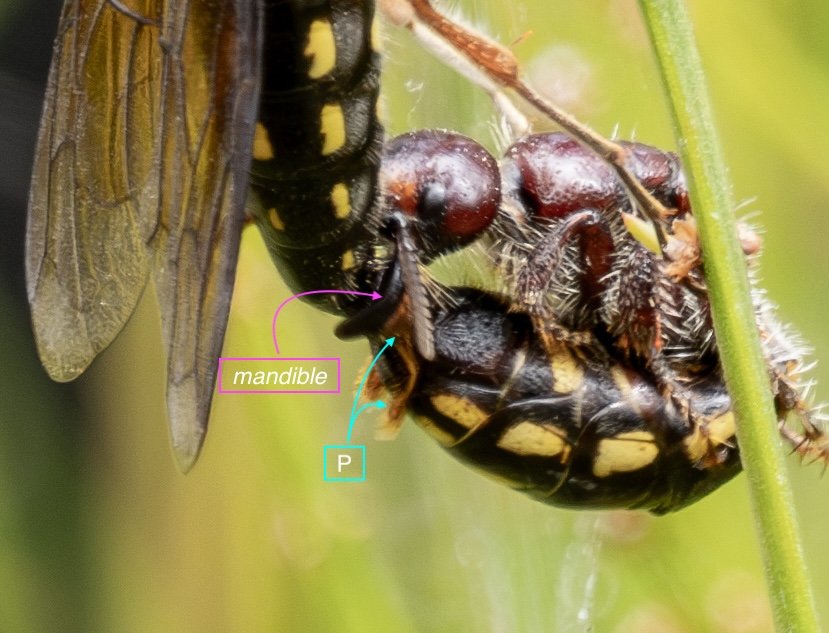

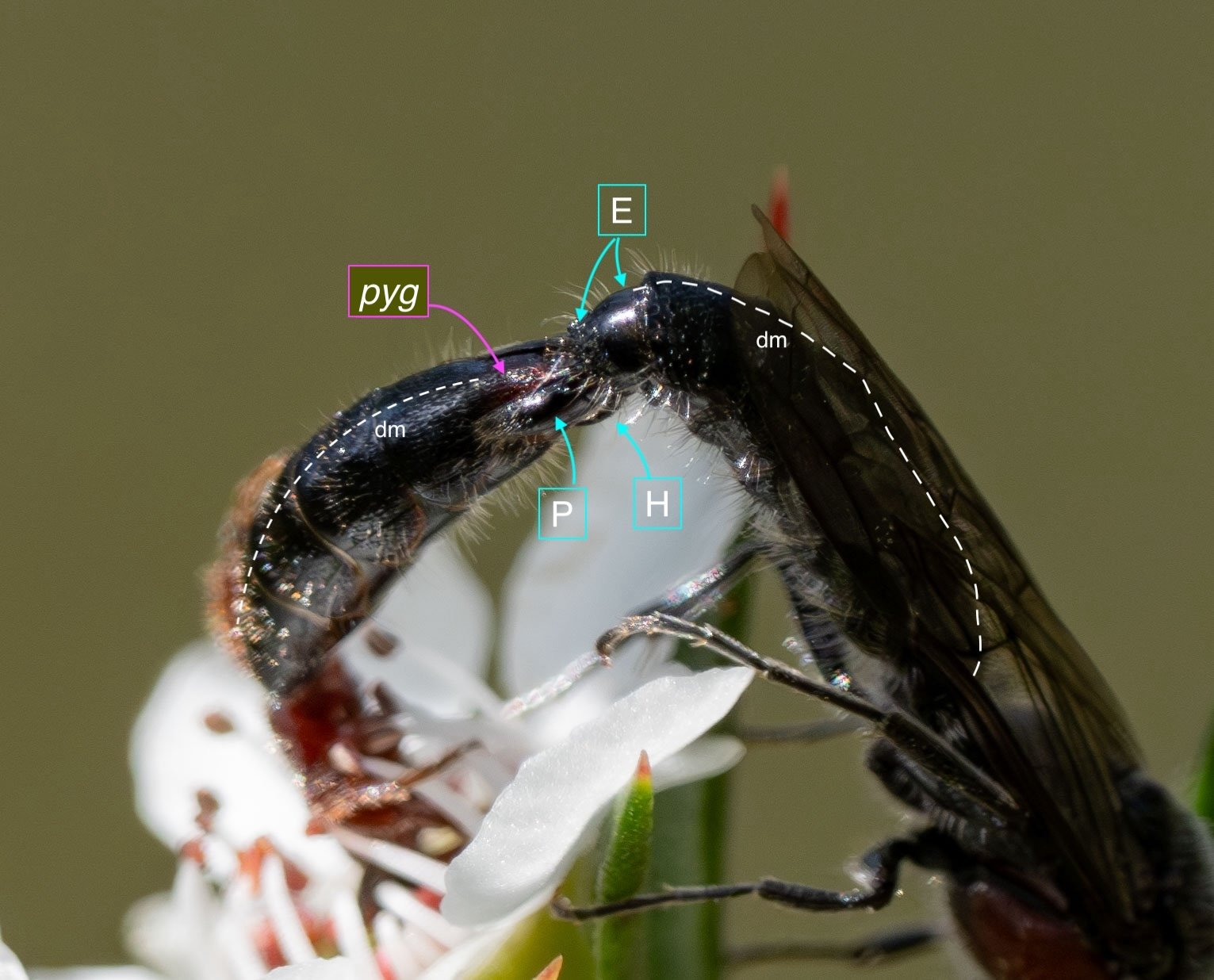

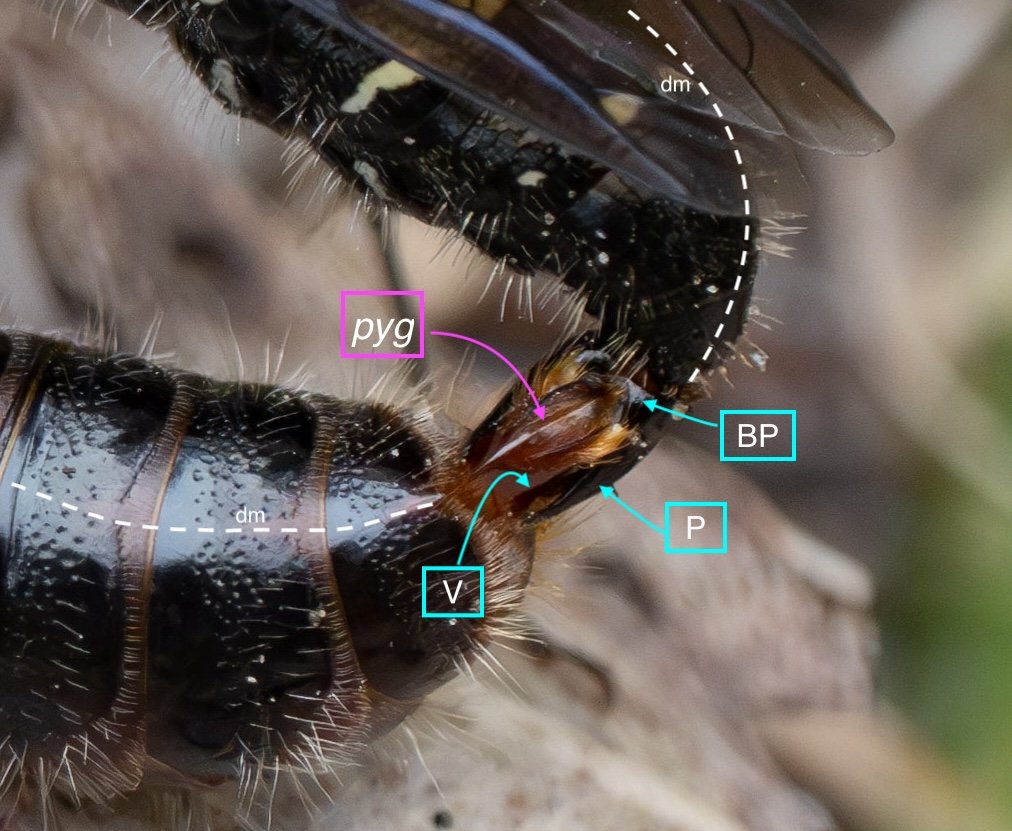

The bite. This is the archetypal thynnine position, with the female curled beneath the male, gripping the end of his body with her mandibles. In this species, the very large mandibles are well-suited to the task! Note that in this position, the phallus is fully inverted (‘Step 3’).

Broad pygidium, with lateral notches that accommodate the cuspids of the volsellae. This is a feature of Catocheilus, and these strong sclerites probably help hold and support the female in position. I also note that in Catocheilus, “the shape of the pygidium of the female is unique within the Australian Thynnini” (Brown 1998, p. 90).

Distinctive parameres, with long, dense hairs on the inner surface of the narrow, apical arms. Brown observed that these hairs may serve a sensory function (rather than to increase grip), suggesting that in Catocheilus the pygidium (rather than the parameres) plays the dominant role in stabilising the coupling (Brown, 2000).

The BP-P suture is not evident here … another feature consistent with the diagnosis of Catocheilus (Brown, 1998).

13th December, 2022

Phallus inverted and therefore both wasps are able to cling to the same substrate. This is one of the orientations depicted in Step 3 of the schematic (Part 3).

Volsella visible, below and medial to the large paramere. Not only does the volsella serve to separate the female sclerites during the initial coupling, its shape is implicated in ensuring the association is between wasps of the same species (Brown, 2000).

13th December, 2023

Phallus inverted and the epipygium extended. The smooth, basal half of the epipygium is normally concealed beneath T6.

Large parameres and a distinctive epipygium. In conjunction with the elongate shape of the female metasoma, this should help with genus ID … when I get around to chasing it down.

23rd January, 2024

Mid-twist. Volsella visible, medial to paramere, and a clear shot of the pygidium. Might this be the same species as Example 3?

Soon to disengage. Phallus now fully inverted as the female twists away.

Immediately after uncoupling, the phallus still inverted and fully exserted.

The male rests for a few seconds before flying off. The phallus is still exserted, but has started to twist back (clockwise) into its natural orientation.