My first Cerceris sighting of the season. I had been closely monitoring their patch, so I do think I caught the earliest action. This little female started adult life back in early April. She mated soon after emerging from her natal burrow, and then returned below ground for the winter. As with most insects, the sperm was delivered in a sealed package (‘spermatophore’) and stored within her body until she is ready to use it. With the approach of spring she emerges to begin her adult life in earnest. There will be no males on the scene for many weeks yet, but she doesn’t need them.

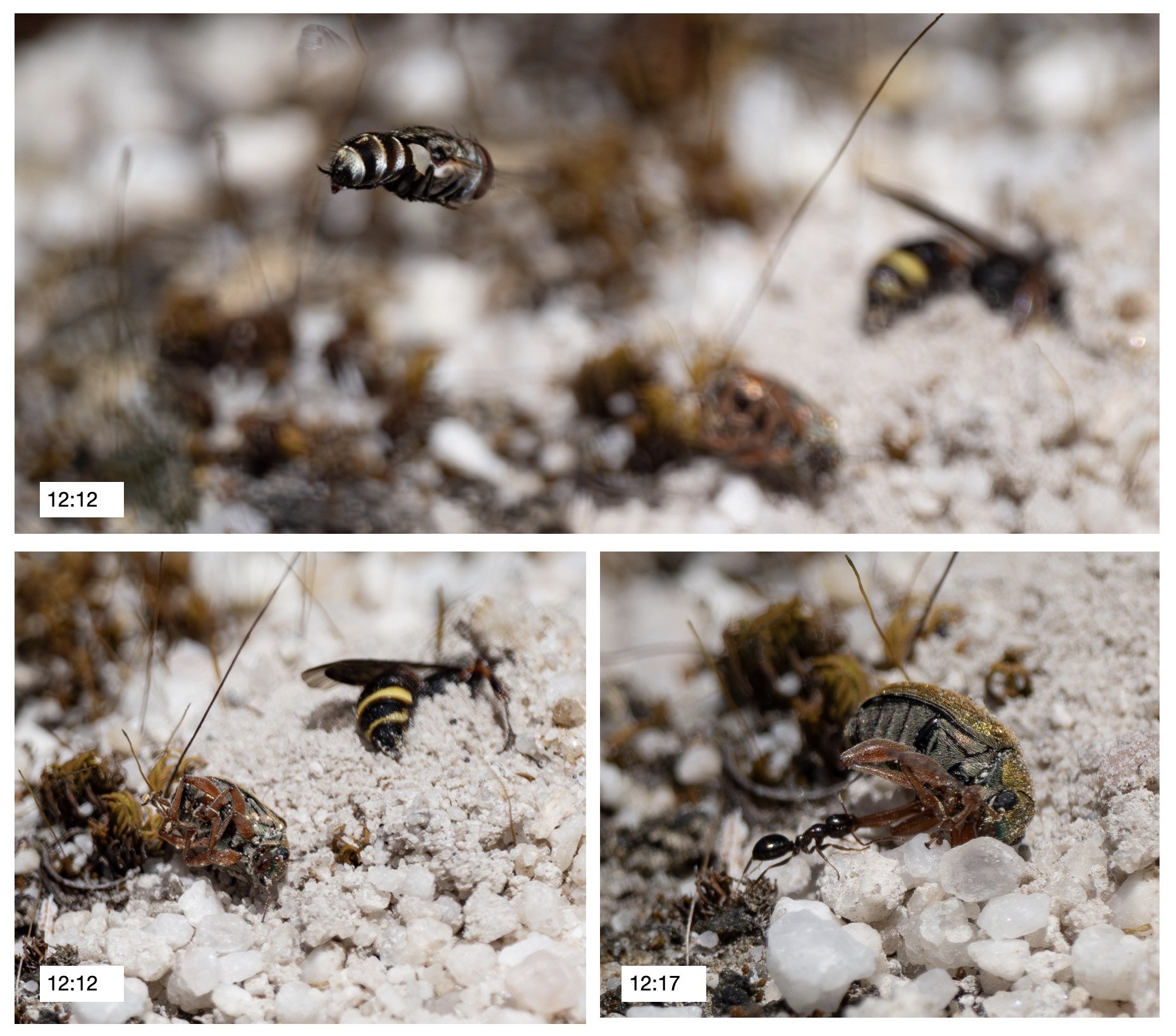

Returning from a successful hunting trip. The beetle is paralysed, but not dead. When she judges she has enough beetle bodies to feed one larva from hatching to pupation, she’ll seal the chamber with a single egg inside … and then start providing for her next offspring.

Typically a prey laden female flies slowly over the nest ground, locates her burrow from the air, then quickly plunges out of sight. This one, however, landed briefly and took a good look at the human with the camera. Having apparently decided I was no threat, she then dived into her open nest. (Such infrequent photo opportunities are always welcome!)

A blocked burrow! This is not an uncommon problem for returning wasps. When she left, the burrow was open but having returned with her catch she finds it covered in sandy soil. Perhaps a passing wallaby had stomped on the mound – that certainly does happen at times. But in this case I suspect another culprit – more on that in a moment.

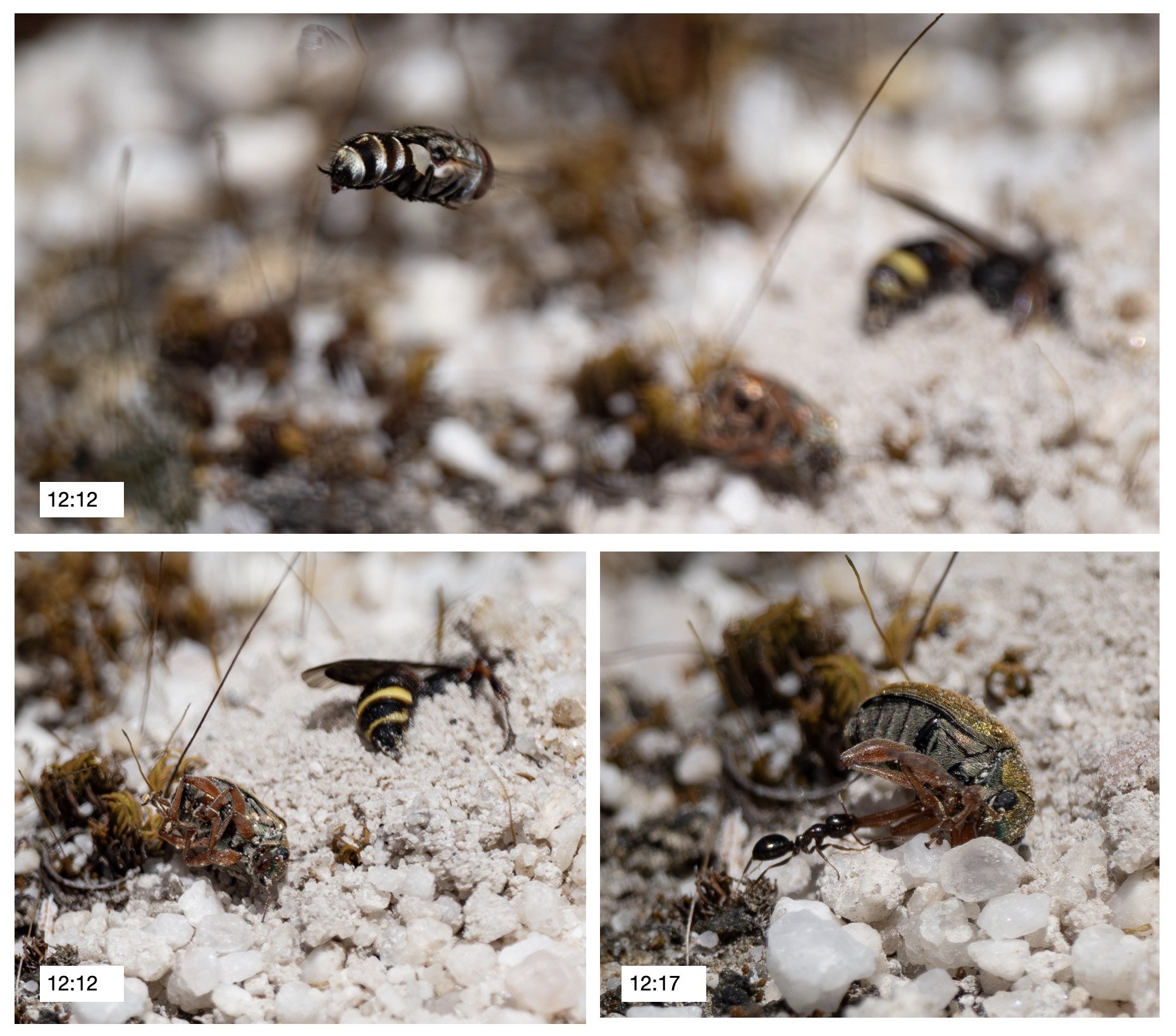

She persisted in her digging, abandoning the beetle on the edge of the mullock heap. Her activities, and the shiny beetle, attracted considerable attention. Satellite flies hovered overhead, briefly. The paralysed, twitching beetle was defenceless against the depredations of ants. And as the wasp seemed to forget about the beetle once she had successfully re-entered the burrow, I decided to ‘rescue’ it from the ants. Just what are these little beetles that the wasps are gathering in such large numbers?

It is a leaf beetle (CHRYSOMELIDAE), most likely of the subfamily Eumolpinae. It might be in the genus Edusella, but I have a bit of work to do before I’d confidently take the ID to genus, let alone species. But Edusella is a reasonable first-guess, as they are known prey of Cerceris antipodes (Evans & Hook, 1986), they do look quite similar (see iNat sightings of E. perplexa, for example), and some species feed on the leaves of Acacia. We certainly have plenty of wattles within easy reach of the Cerceris nests!

A little later, when I next checked, the burrow was open again. A prey-laden wasp approached but instantly backed off, dropping her prey near the entrance. Almost immediately another wasp reached out from the burrow and dragged the beetle below!

The exiled wasp repeatedly tried to enter the nest, but was repulsed each time. In the last photo (bottom right), the antennae of the resident wasp are visible. Clearly a Cerceris, and clearly intent on barring the entrance. Cerceris antipodes are known to share burrows, but the relationship is not always entirely amicable … clearly!

No prizes for guessing why these little pests are called satellite flies! Incoming, prey-carrying wasps are routinely orbited by a hovering miltogrammine fly … or two. The moment the wasp enters her nest, the flies land on the rim of the burrow and will often disappear inside.

This photo was taken immediately after a satellite fly landed briefly on the rim of the burrow. I watched the wriggling little fly larva (arrow … and yes, it’s rightly named a maggot) hang there for a few seconds, before it dropped into the nest opening. Once inside the burrow it would seek out a paralysed beetle. Ultimately, if it successfully evades the attention of the home owners, it will consume the food stashed in a Cerceris chamber, kill the host young, and ultimately pupate within the safety of the underground nest.

It’s an effective strategy. Miltogramminae (SARCOPHAGIDAE) are “major mortality factors for many if not most aculeate (stinging) wasp species” (Marshall, 2012, p. 385).