First bee of the season!

Well, my first good sighting anyway. Trichocolletes are almost as large as honey bees, but their pattern of flight and the pitch of their buzzing makes them quite easy to track. And I always check the Hardenbergia flowers – these purple peas are Trichocolletes’ favourite! The pollen-loaded legs tell me this is a female.

Trichocolletes (COLLETIDAE)

Males & females

This is a male … the number of antennal segments is a reliable way to sex bees (and many related wasps). Males have 11 segments in the flagellum (plus scape & pedicel), females just 10. He’s also lacking the pollen-carrying hairs of Trichocolletes females. But a note of caution: while a visible pollen load = female, ‘no pollen’ does not = male. Not all bees transport pollen on the outside of their bodies. Many colletids, such as Euhesma, swallow it instead.

Trichocolletes (COLLETIDAE)

Small but distinctive

Many native bees are small and easily overlooked. This one is just 5mm long, but the metallic blue-green thorax and reddish abdomen is quite eye-catching. Clues to identity include: the extendable ‘arm’ of the mouthparts (= family Halictidae); shape of abdomen, with pollen-carrying hairs underneath (= genus Homalictus). The shiny thorax is also a common feature of Homalictus.

Homalictus (HALICTIDAE)

Native bees vary greatly in size

The fragrant, bearded flowers of Styphelia ericoides are a magnet for nectar feeders, large and small.

Trichocolletes (top) (COLLETIDAE); Homalictus (bottom) (HALICTIDAE)

Reed bees are common

Exoneura is an endemic Australian genus of relatively hairless bees. They often have white or yellowish markings on the face.

Exoneura (APIDAE)

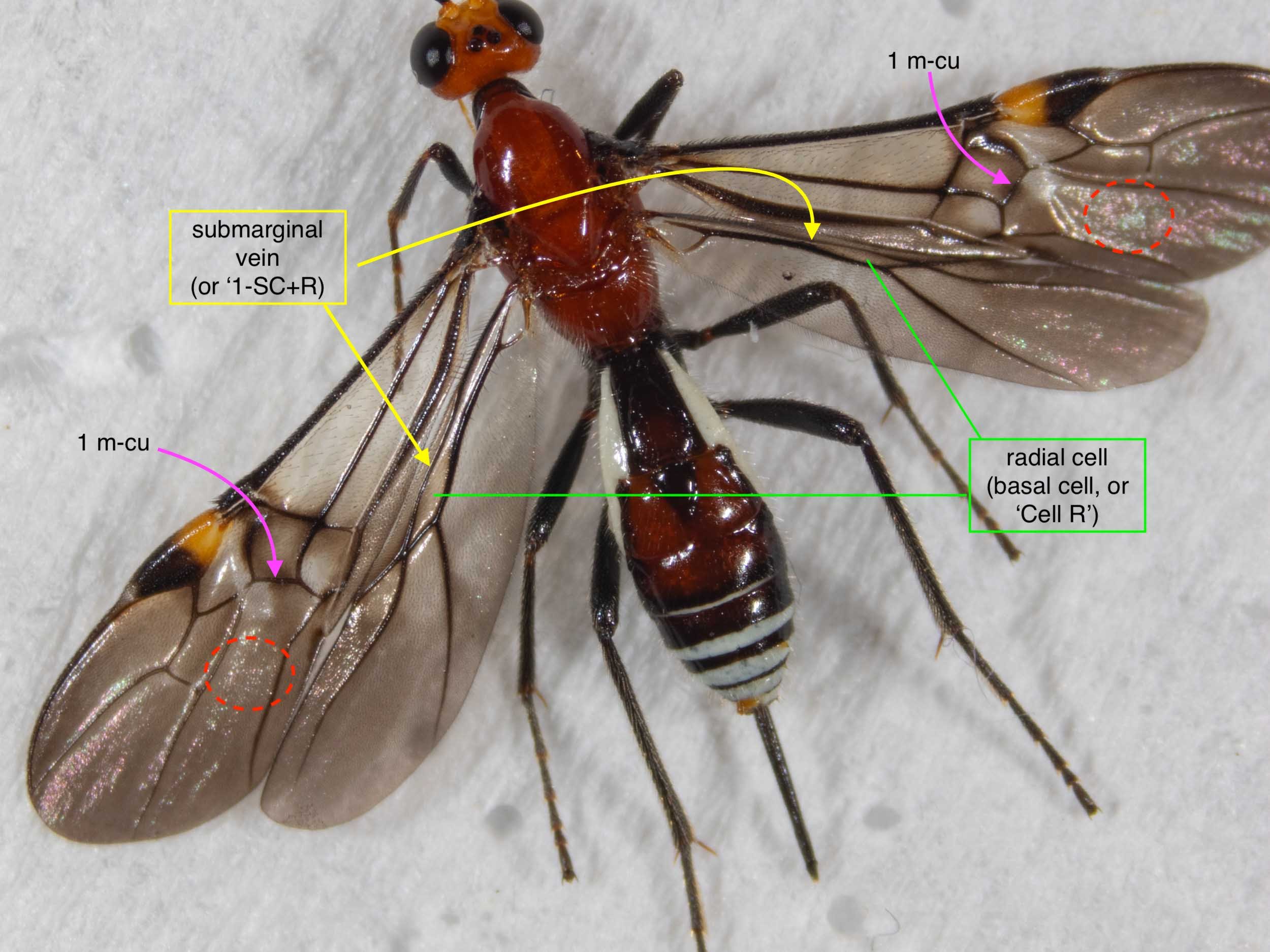

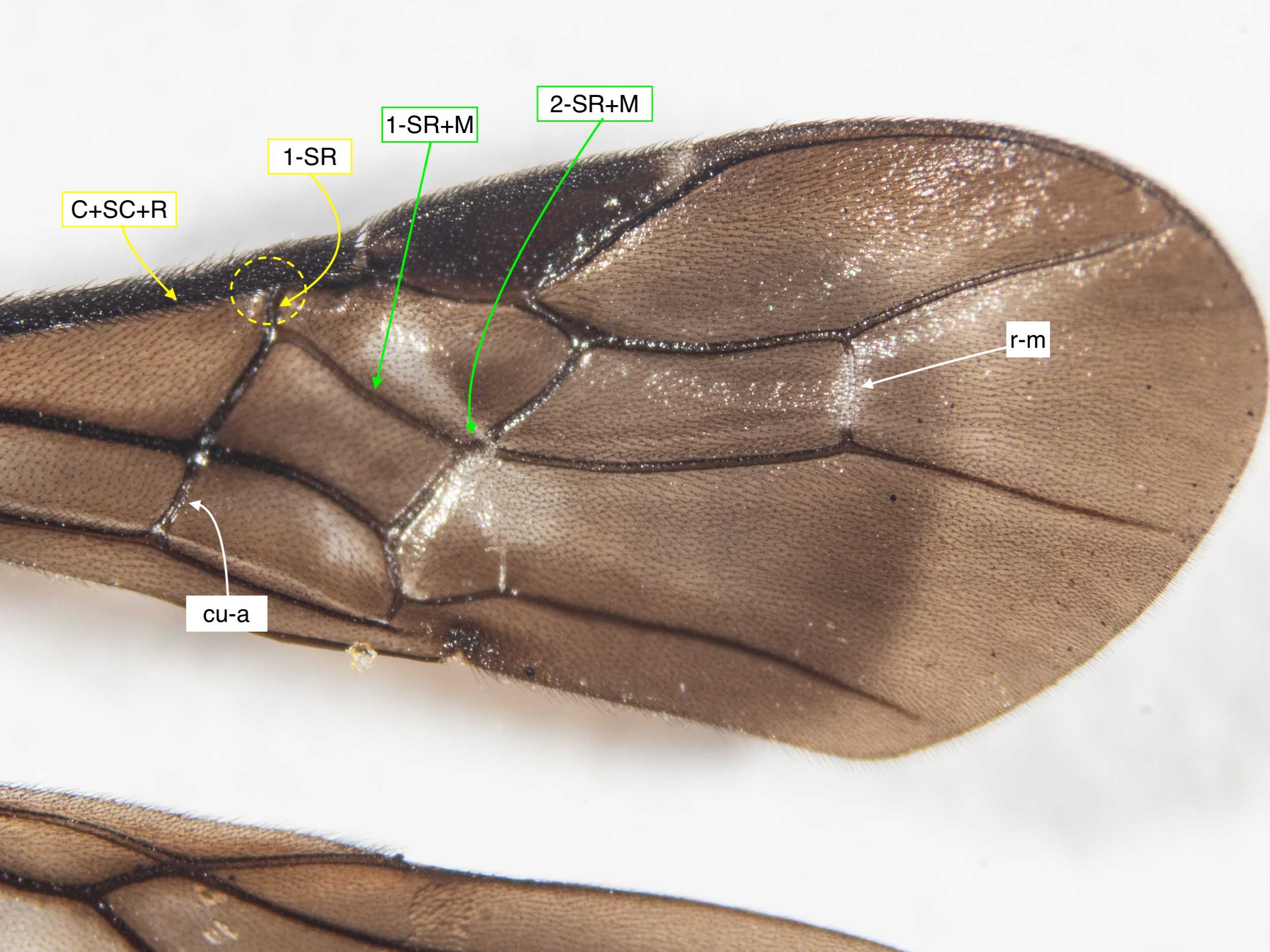

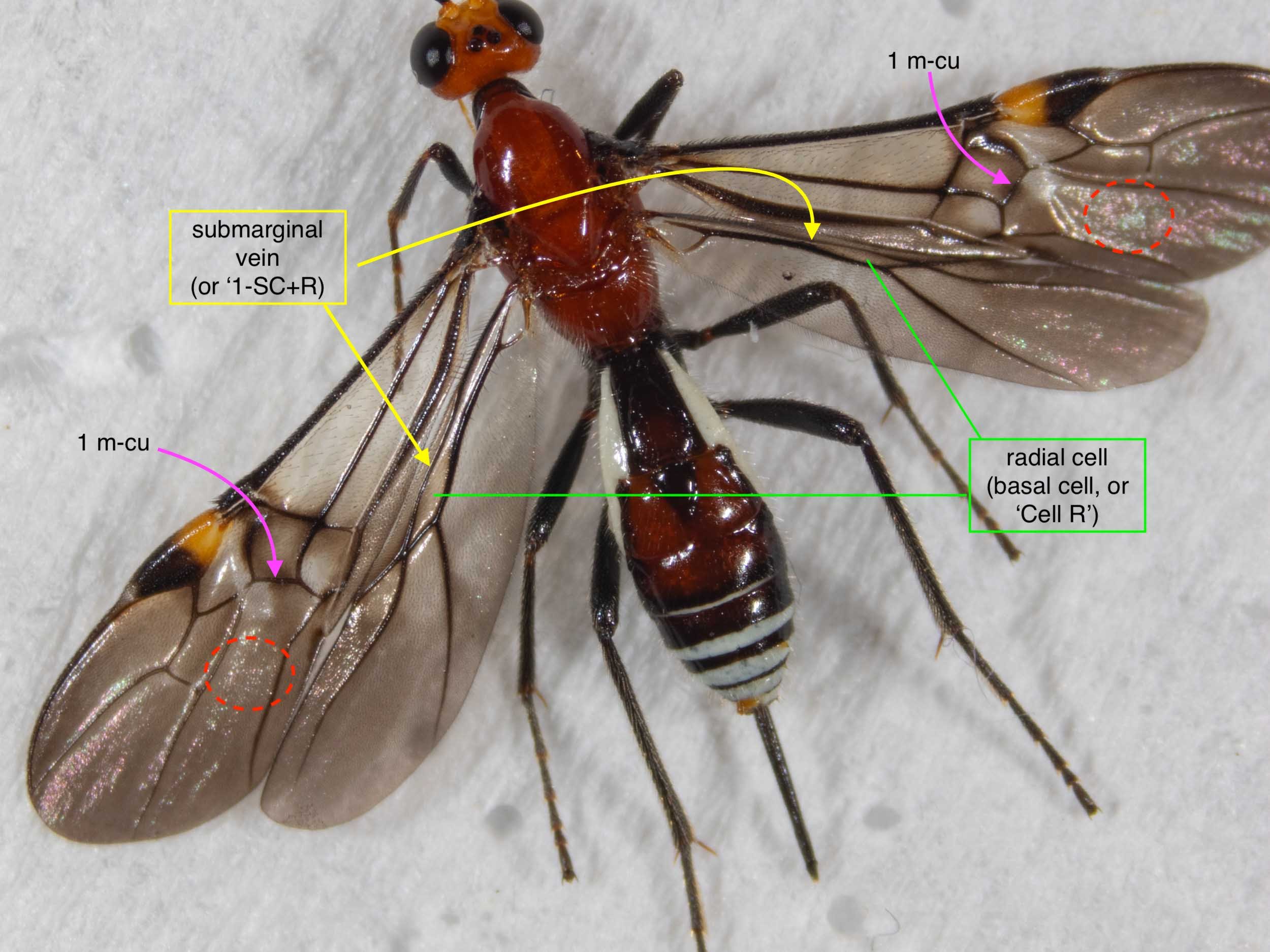

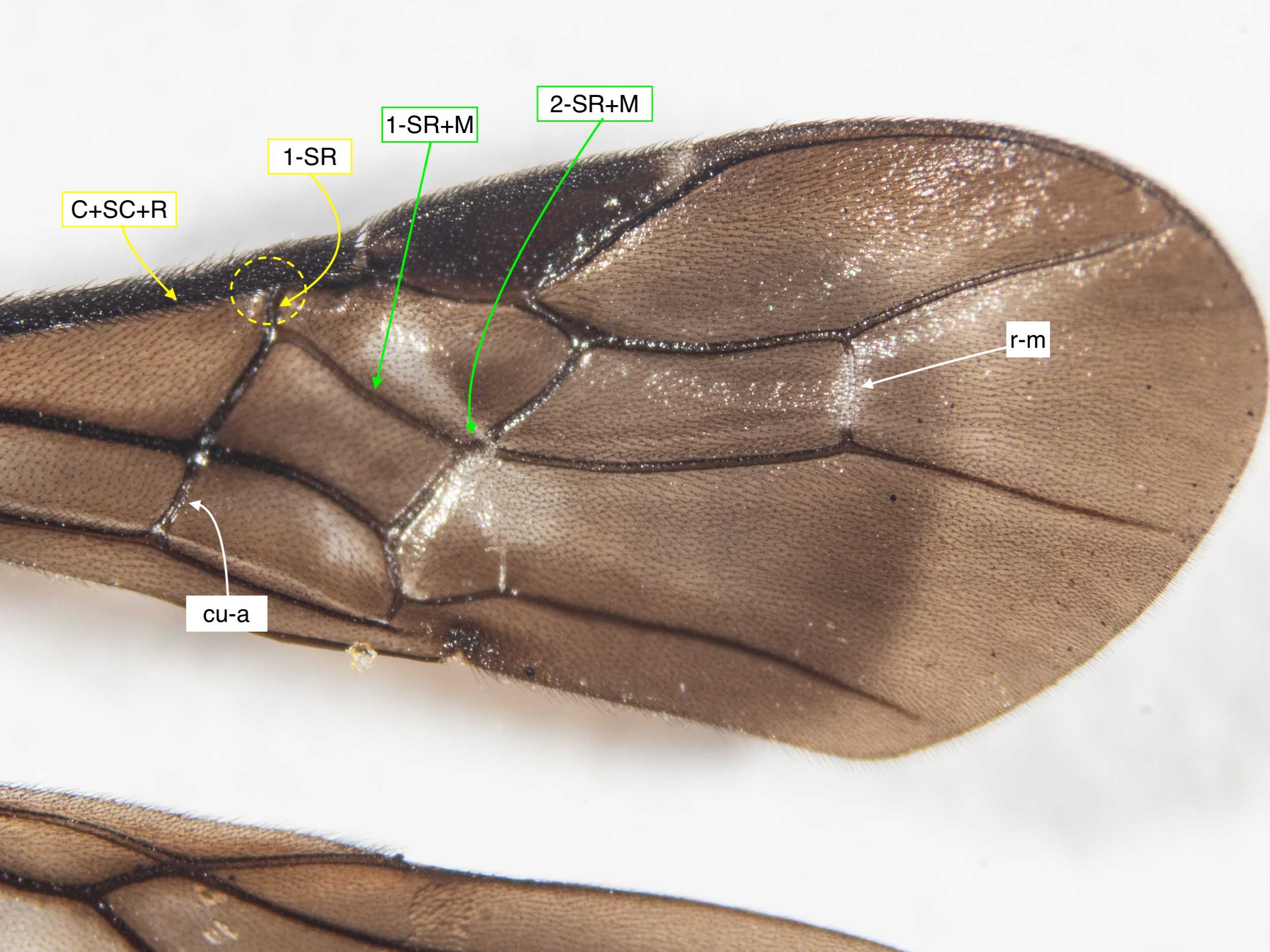

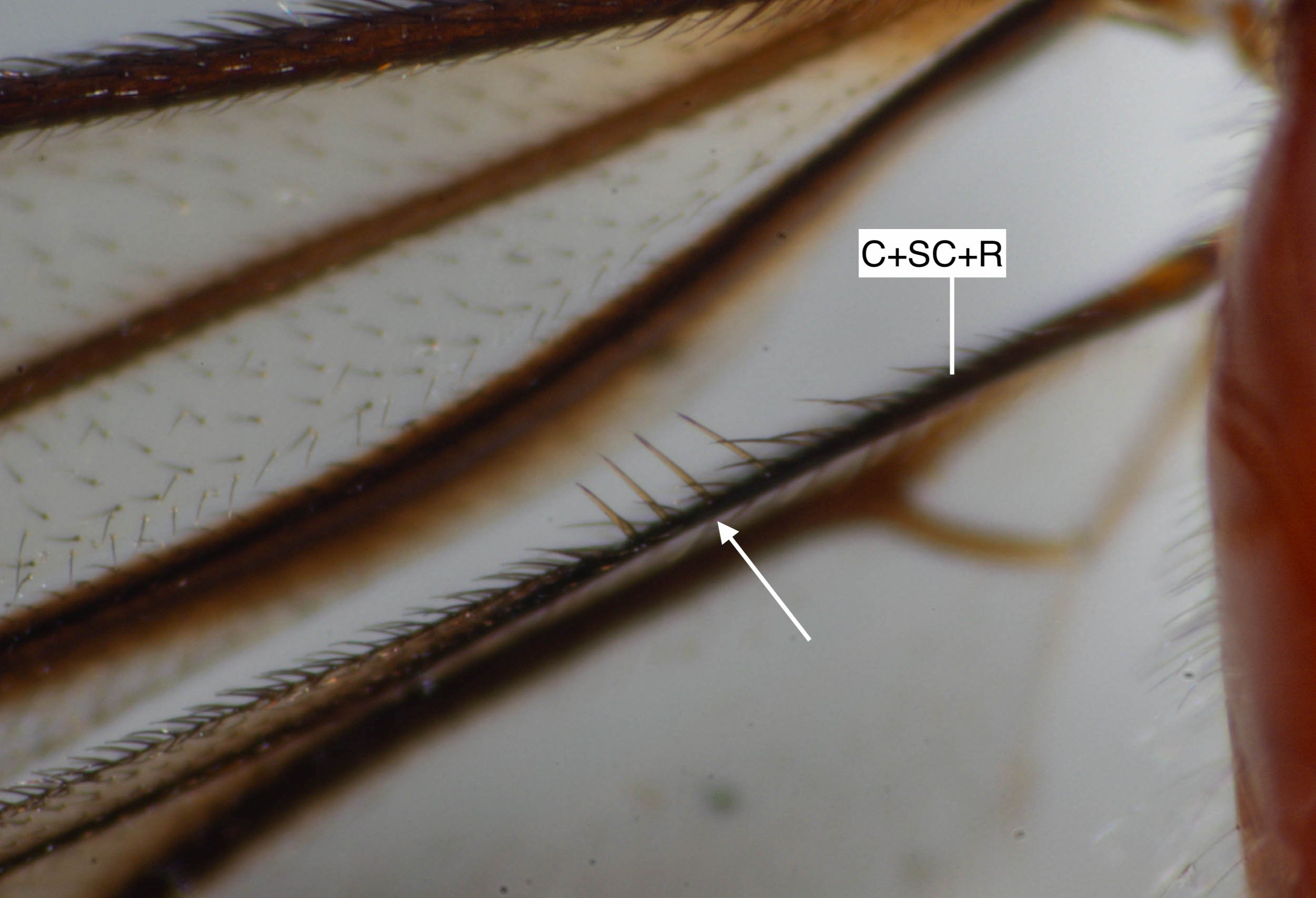

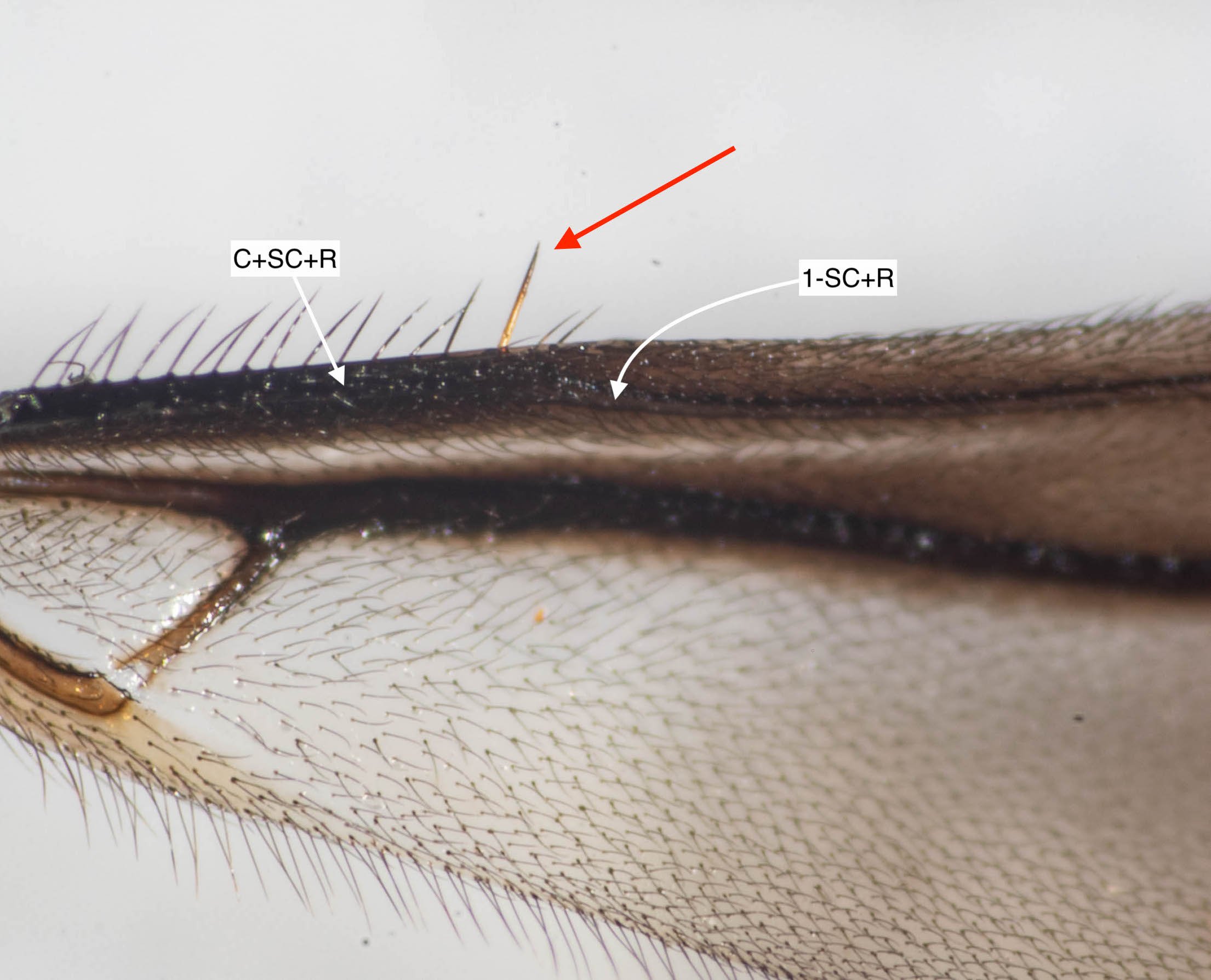

Wing venation helps with ID

I tend to look for the ‘cut-off’ abdomen when identifying Exoneura. But the most definitive character is the pattern of veins in the forewing. This is true for many hymenoptera, so I’m always pleased to get a wing shot like this one.

Exoneura (APIDAE)

Hairy-faced male bee

Some species in this subgenus have unusually large eyes and long black hairs standing erect on the lower face. They swarm, presumably in order to attract mates. And that is exactly what this hairy little bee was doing when I noticed him. Occasionally one would land and take a feed of nectar, but otherwise they were hovering about in a cloud above a single Styphelia bush.

Exoneura (Exoneura) (APIDAE)

First time I've sighted this species

Reasonably large, bright red thorax, shiny black abdomen … certainly distinctive! Yet I don’t recall ever seeing this species before. With some help from the iNaturalist community, I now have a name.

Lasioglossum (Callalictus) callomelittinum (HALICTIDAE)

Green-and-gold Nomia Bee

This species is large, colourful, and a common sight in the forest. They share a patch of sandy soil with nesting Cerceris wasps and, like the wasps, appear to be reusing burrows from last season.

Lipotriches australica (HALICTIDAE)

Unusual behaviour

Not every bee I spot is flower-feeding or nesting. Some perch to rest or groom, and at night males will often roost among vegetation. But I’m not at all sure what this male was up to. He repeatedly probed among the dried fruits of this sedge. It was the middle of the day, he was active and alone … it remains a mystery.

Leioproctus (?) (COLLETIDAE)

Careful grooming, despite the wear & tear

Antennae and mouthparts are important equipment for many insects, bees included. Using brushes on his front legs, this rather worn male wipes clean his extended mouthparts.

Trichocolletes (COLLETIDAE)

More grooming

Antennae require frequent, careful maintenance – particularly for males. The flagellum contains hundreds of sensory organs. Some are tactile, but many are used to detect airborne chemicals … including female pheromones.

Trichocolletes (COLLETIDAE)

The recognised 'pea technique'

Pressing down on the lateral petals in order to reach the nectar in the throat of the pea flower, exposes the stamens in the perfect position to dump pollen on the underside of this visiting bee.

Lasioglossum (Chilalictus) (HALICTIDAE)

A tiny, shiny Masked Bee

This really is quite a small bee. The Aotus flowers provide an excellent scale for comparison.

Hylaeus (COLLETIDAE)

Unorthodox access

For such a small bee, this is perhaps the only way to get to the pollen. And as colletids ingest pollen and transport it in their crops, rather than on specialised hairs, they need to chew on the anthers and not simply brush them with their bodies.

Hylaeus (COLLETIDAE)

Really quite a large bee

Compare with the other pea-feeding bees. Same species of flower, much bigger bee!

Lipotriches australica (HALICTIDAE)

A novel crane fly

Large and beautifully patterned … yet a species we’ve not recorded here before.

Ischnotoma eburnea (TIPULIDAE: Tipulinae)

Stiletto fly

A predictable sight in spring, as males hover in loose swarms, periodically landing and holding their front legs aloft.

Ectinorhyncus (THEREVIDAE)

Early emergence, fewer predators

These rather stocky stiletto flies are a favoured food for one of our sand-nesting crabronid wasps, Podagritus. Luckily for this fly, the wasps are not due to appear before late October. The larvae of stiletto flies are wiry, elongate, free-living soil predators. As adults, the flies rarely visit drink and are not often seen at flowers.

Anabarhynchus (THEREVIDAE: Therevinae)

A first for us, and for iNat

This fly looked a bit different to our usual Anabarhynchus, so I put the sighting up onto iNaturalist. It was rather quickly identified to species level by those in the know … three taxonomists, each specialising in therevids and related flies. And this is the first identified photo of this species on the system. I’m feeling rather chuffed!

Anabarhynchus calceatus (THEREVIDAE: Therevinae)

Another rarely-recorded therevid

Small, hanging about the Cerceris nesting patch day after day … and again identified to species level by the experts. My first sighting of this species was in November last year, in exactly the same area. That was the first iNaturalist record (and the only ones added since then have been my sightings, here in the forest). These little flies are either rare or are simply not attracting the attention of nature photographers. Perhaps it’s a bit of both.

Bonjeania argentea (THEREVIDAE: Agapophytinae)

A mated pair

This week, a pair ‘in copula’. Another first.

Bonjeania argentea (THEREVIDAE: Agapophytinae)

Yellow-shouldered Stout Hover Fly

During the summer months, hover flies are obvious and ubiquitous. But for now, sightings remain a special treat.

Simosyrphus grandicornis (SYRPHIDAE)

Photo-friendly flies

Metallic and common, flies in this family are a common sight in the forest and familiar to anyone with a vegetable garden. As adults, these pretty little flies hunt tiny prey such as springtails, minute worms and flies. The larvae are soil-living predators.

SCIAPODINAE (Sciapodinae)

An unusual bee fly

This uniquely Australian genus was, until recently, known from just this one species. Now there are two … so still a very small taxon. Nothing is known about their biology, and this head-down, bottom-up posture is puzzling (see my iNat sighting for discussion).

Marmosoma sumptuosum (BOMBYLIIDAE: Bombyliinae: tribe Marmasomini)

Our showiest bee fly

Flashing silver-white in the sun, buzzing at a distinctive, high frequency (or ‘pitch’), hovering low to the ground, and frequently landing on vegetation. These fluffy little flies are a personal favourite of mine.

Meomyia albiceps (BOMBYLIIDAE: Bombyliinae: tribe Bombyliini)

Yet another 'sand chamber' fly

Bee flies of the subfamily Bombyliinae are also called sand chamber flies. They have a modified abdomen into which they gather sand to coat their sticky eggs before dropping them into the environment. Mind you, I’m not sure if this particular individual is a male or female.

Staurostichus (BOMBYLIIDAE: Bombyliinae: tribe Bombyliini)

Long-winged bee fly

First sighting for the season, on a day when bee fly diversity suddenly took off. Four species across 3 genera in a single day! Aleucosia is one of Australia’s most common and easily recognised genera, yet their biology is poorly known.

Aleucosia (BOMBYLIIDAE: Lomantiinae)

Yellow-spotted Blue butterfly

This was the first sighting for the season. They are now one of the more common butterflies in flight. Many species have yet to make an appearance.

Candalides xanthospilos (LEPIDOPTERA: LYCAENIDAE)

Adults feed widely, but larvae are picky eaters

The larvae of this species usually feed on Pimelea, a plant that boomed in the wet, post-fire seasons but which is notably sparse this spring. I predict fewer emergent adults next year, as a result.

Candalides xanthospilos (LEPIDOPTERA: LYCAENIDAE)

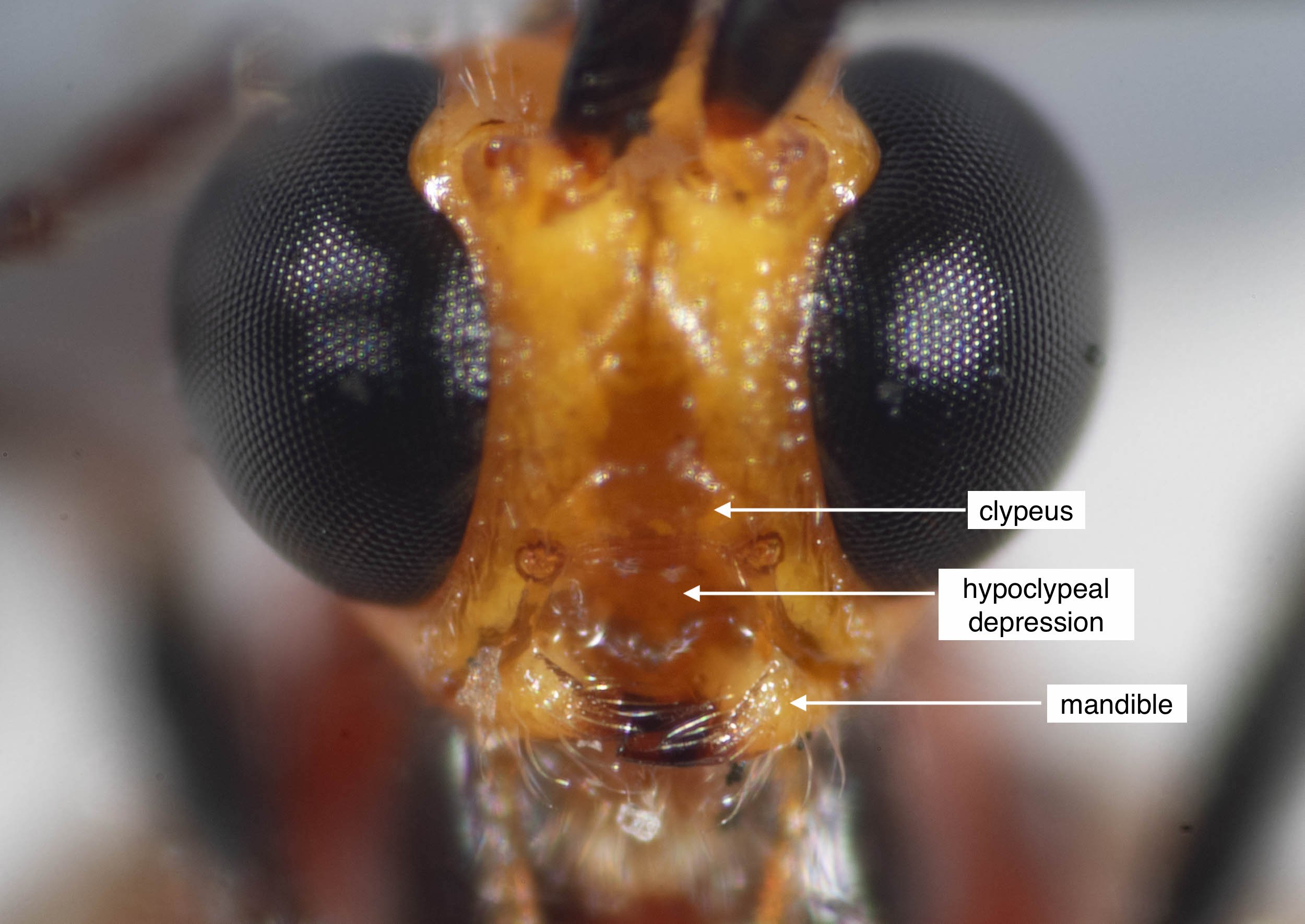

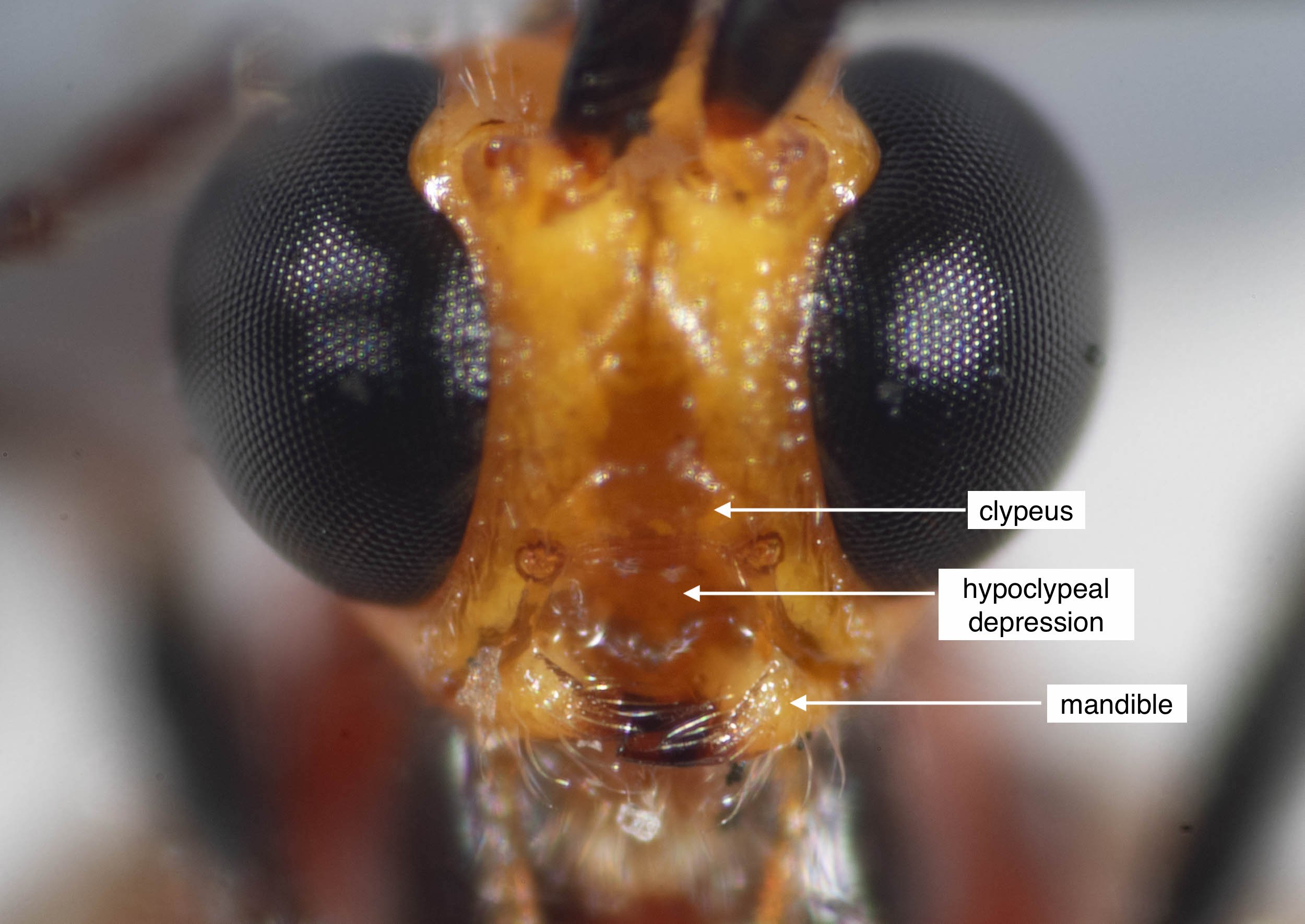

Female flower wasp

Female flower wasps lack wings … that’s obvious. Less apparent is the modification of their mouthparts. They have mandibles adapted for grasping the male, but palps and other parts normally used for manipulating food are greatly reduced. They don’t need them. Feeding for a female flower wasp typically involves immersing her head in a large drop of liquid regurgitated by the male, and simply drinking.

Males often hold the drop beneath their face and head, and the female reaches up for it. But in most of our local species, a different method is used: the drop is held at the end of the male’s abdomen, and the female can access it without uncurling from her typical in-flight position.

subfamily Thynninae (HYMENOPTERA: THYNNIDAE)

Newly-emerged from the soil

One of our largest local flower wasp species, and also the most colourful. I spotted this dirt-covered female soon after she emerged from the soil. Perhaps she was a virgin, emerging into the sun for the first time. Or she may already have mated, burrowed to locate a beetle larva on which to lay an egg, and be preparing to start the mate-feed-egg laying cycle again. Either way, she climbed onto low vegetation and waited, no doubt emitting pheromones to call in a male.

subfamily Thynninae (HYMENOPTERA: THYNNNIDAE)

3 days on, still waiting

For several days, when I looked for her, there she was. Less dusty now, but again clinging to grass stems and sending out her chemical call. I think she went to ground at night, climbing back up when it was warm and sunny. I’m quite confident this is the same individual – they’re really not a common sight, and she was always in the exact same spot (albeit on a different plant stem each time). It’s early in the season, and I’ve yet to see many larger flower wasps on the wing. I guess she has little choice but to wait.

subfamily Thynninae (HYMENOPTERA: THYNNIDAE)

Not a wasp

The mimicry is good – slender body with a narrowed waist, long legs, wings that look folded. But this is actually a beetle.

Enchoptera apicalis (COLEOPTERA: CERAMBYCIDAE)

Nectar feeders as adults

Cerambycid larvae usually feed inside plant tissue, including both living and dead wood. Enchoptera is not an uncommon genus, yet nothing is known about its choice of host plants. The adults are often seen feeding at flowers … and this one was competing with bees for Styphelia nectar.

Enchoptera apicalis (COLEOPTERA: CERAMBYCIDAE)

Wandering Ringtail damselfly

Male damselflies wait for receptive females alongside a suitable body of water – in this case, our small frog pond. They defend their chosen patch from incoming rival males.

Austrolestes leda (ODONATA (ZYGOPTERA): LESTIDAE)

Circling about an open, sandy patch of ground, clearly intent upon something in the soil.

When perched on vegetation they were often head down, close to ground.

Even with the naked eye, their bodies flashed colourfully in the sun.

Securely held by the 'shoulders'

Male odonata have two pairs of appendages at the end of the abdomen which they use to grip a receptive female. In the case of damselflies, he holds her by the pronotum (first segment of the thorax).

Austrolestes leda (ODONATA (ZYGOPTERA): LESTIDAE)

Tau Emerald dragonflies

The site of hold in dragonflies and damselflies differs. In dragonflies, the male grips the female by the back of the head, rather than the thorax. Given the large eyes and head of most dragonflies, perhaps this is simply a better solution to their common problem.

Hemicordulia tau (ODONATA (ANISOPTERA): HEMICORDULIIDAE)

Odonata mating is a bit odd

In damselflies & dragonflies sperm transfer is a bit of a round about affair. Once the male has secured a female, he transfers his sperm from the tip of his abdomen (where it’s produced), to his 2nd abdominal segment (for temporary storage). Only then does the pair form the classic ‘wheel’, as she brings the end of her body up to accept the sperm.

Austrolestes leda (ODONATA (ZYGOPTERA): LESTIDAE)

She inserts her eggs into pond plants

In this species, egg-laying females are often accompanied by their most recent mate … still held securing in his grip. But sometimes they go it alone.

Austrolestes leda (ODONATA (ZYGOPTERA): LESTIDAE)

Jewel beetle mating swarm

It’s not uncommon to see male beetles clambering over one another in an effort to secure a female. For a few hours, on this one day, a single Aotus bush played host to dozens of these bronze-coloured jewel beetles.

Ethonion (COLEOPTERA: BUPRESTIDAE)

Flying Peacock spider

This colourful jumping spider is tiny, and surprisingly easy to overlook among the leaf litter. Unless he’s in the sun!

Maratus volans (SALTICIDAE)

The pond attracts mud-nesting wasps

Many insects obtain all the water they need from nectar feeding or morning dew on leaves. But the water requirements of a mud-nesting wasps go well beyond thirst. She repeatedly fills her crop with water, flies to a suitable source of soil, and disgorges the water until she can form a ball of mud. (The dry forest has no ready source of pre-mixed mud, except immediately after rain). She then carries the mud ball off to her chosen site for nest construction.

Paralastor (?) (HYMENOPTERA: VESPIDAE: EUMENINAE)

These flowers are moth pollinated ...

… but this is not a moth. Stackhousia flowers are fragrant only at night and the plant is known to attract a variety of nocturnal moths (Blackall et. al., 2023). But might butterflies like this one not also play a role?

Ocybadistes walkeri (LEPIDOPTERA: HESPERIIDAE)

Green Grass-dart, a skipper butterfly

A potential pollinator, but perhaps not an ideal one. This butterfly is clearly carrying pollen, but it will be a mix. She is a generalist. The flowers would do better with specialists, and at night there is less inter-floral competition for potential pollinators.

Ocybadistes walkeri (LEPIDOPTERA: HESPERIIDAE)

Looks like a cone, but it's a gall ...

… housing a small & flightless bug. Some casuarina (in this case, Allocasuarina littoralis) bear many of these rather attractive structures which bear a remarkable resemblance to the developing fruit of the tree. Perhaps this is not so surprising, as the gall is a product of the tree rather than the insect.

Cylindrococcus (HEMIPTERA: ERIOCOCCIDAE)

A particularly bothersome ant

Stick insects, even relatively large ones like this, are usually difficult to spot. Not only do they resemble their perches, but they move slowly or not at all. So I was rather surprised to see this one flailing its legs about wildly. It was even difficult to photograph, as it didn’t stay still for more than a second (and I patiently watched on for several minutes). And then I spotted the cause of the phasmid’s distress – a tenacious ant gripping the end of the front leg. Ouch!

Ctenomorpha marginipennis (PHASMIDA: PHASMATIDAE)

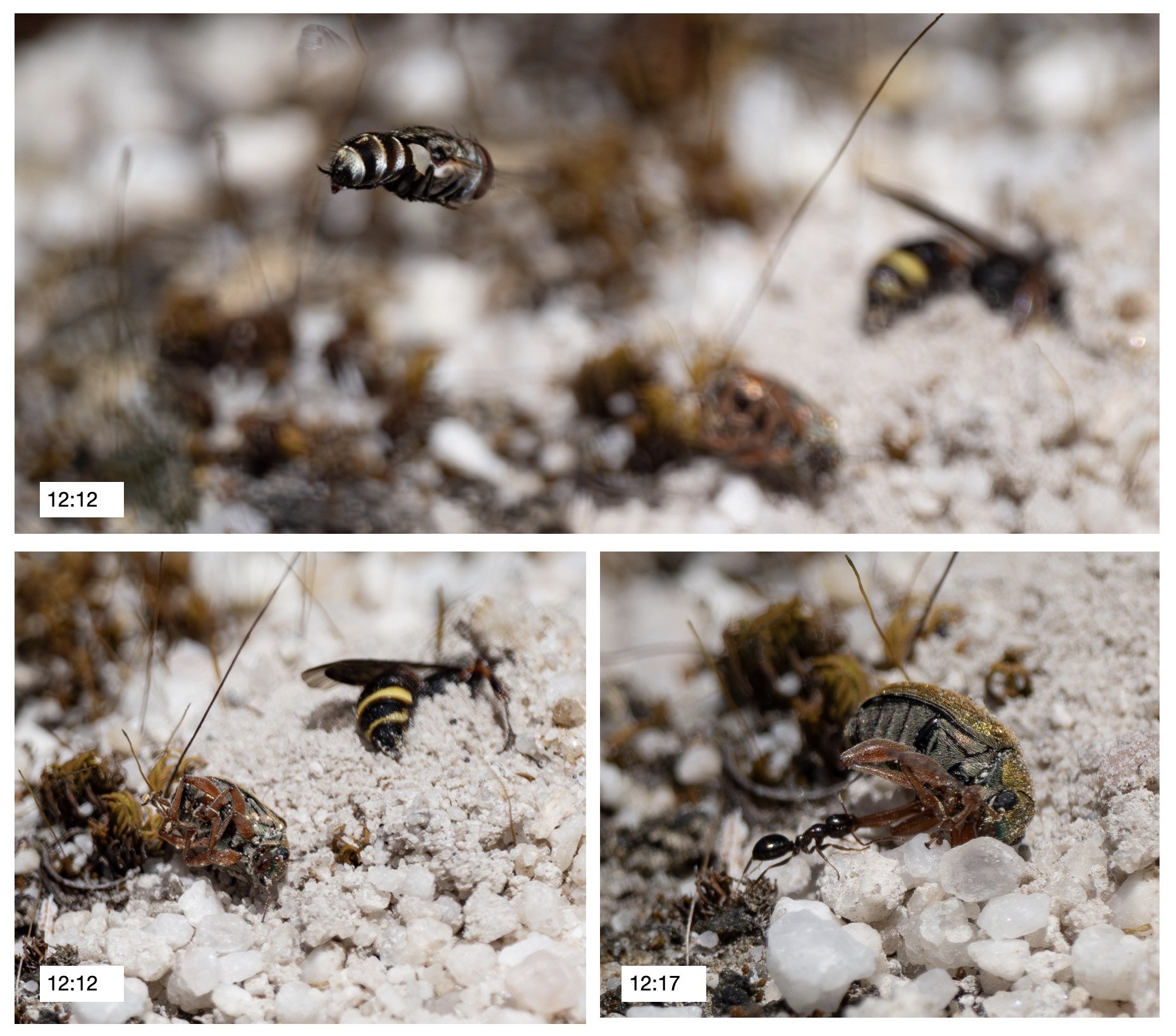

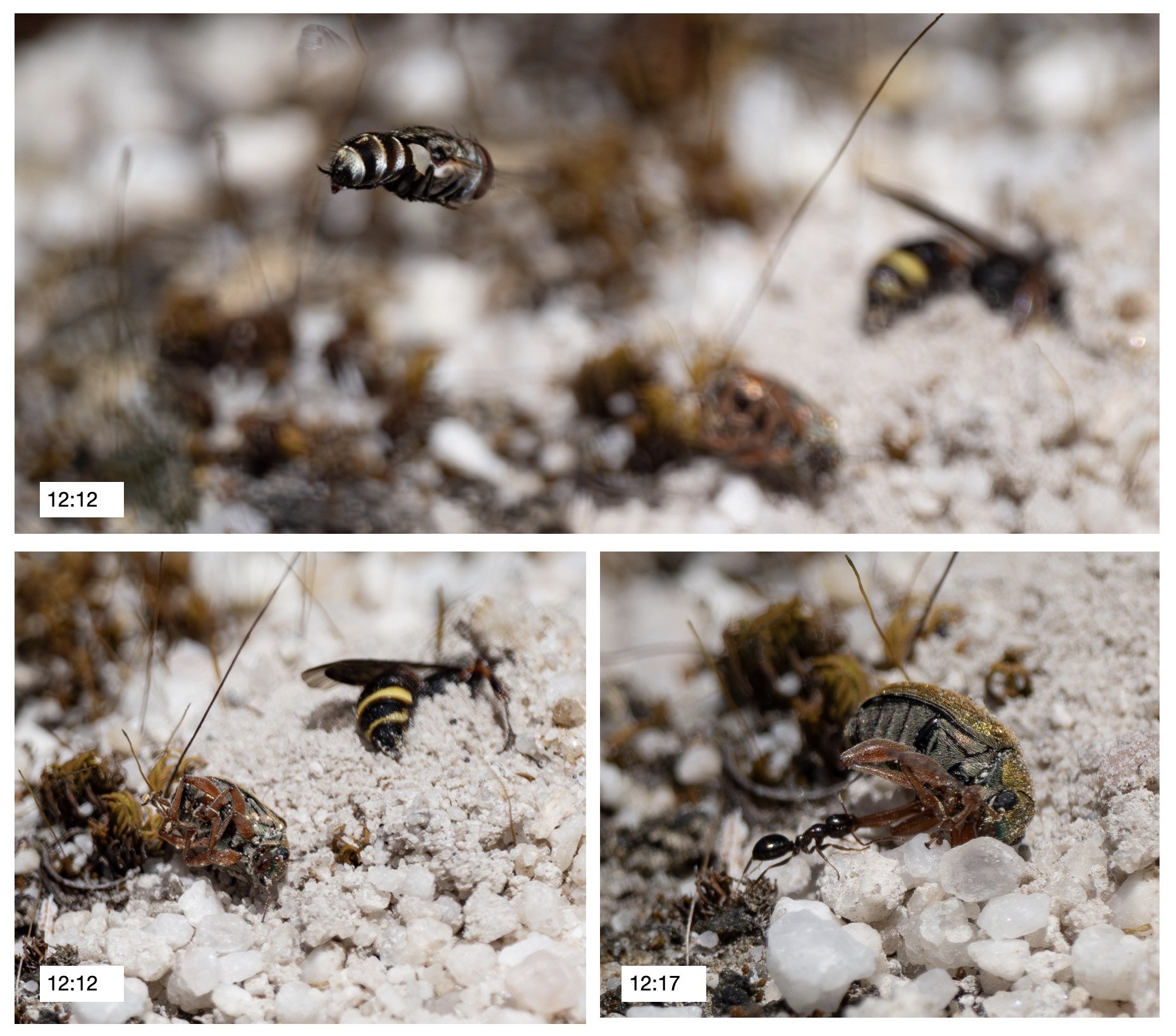

My first Cerceris sighting of the season. I had been closely monitoring their patch, so I do think I caught the earliest action. This little female started adult life back in early April. She mated soon after emerging from her natal burrow, and then returned below ground for the winter. As with most insects, the sperm was delivered in a sealed package (‘spermatophore’) and stored within her body until she is ready to use it. With the approach of spring she emerges to begin her adult life in earnest. There will be no males on the scene for many weeks yet, but she doesn’t need them.

Returning from a successful hunting trip. The beetle is paralysed, but not dead. When she judges she has enough beetle bodies to feed one larva from hatching to pupation, she’ll seal the chamber with a single egg inside … and then start providing for her next offspring.

Typically a prey laden female flies slowly over the nest ground, locates her burrow from the air, then quickly plunges out of sight. This one, however, landed briefly and took a good look at the human with the camera. Having apparently decided I was no threat, she then dived into her open nest. (Such infrequent photo opportunities are always welcome!)

A blocked burrow! This is not an uncommon problem for returning wasps. When she left, the burrow was open but having returned with her catch she finds it covered in sandy soil. Perhaps a passing wallaby had stomped on the mound – that certainly does happen at times. But in this case I suspect another culprit – more on that in a moment.

She persisted in her digging, abandoning the beetle on the edge of the mullock heap. Her activities, and the shiny beetle, attracted considerable attention. Satellite flies hovered overhead, briefly. The paralysed, twitching beetle was defenceless against the depredations of ants. And as the wasp seemed to forget about the beetle once she had successfully re-entered the burrow, I decided to ‘rescue’ it from the ants. Just what are these little beetles that the wasps are gathering in such large numbers?

It is a leaf beetle (CHRYSOMELIDAE), most likely of the subfamily Eumolpinae. It might be in the genus Edusella, but I have a bit of work to do before I’d confidently take the ID to genus, let alone species. But Edusella is a reasonable first-guess, as they are known prey of Cerceris antipodes (Evans & Hook, 1986), they do look quite similar (see iNat sightings of E. perplexa, for example), and some species feed on the leaves of Acacia. We certainly have plenty of wattles within easy reach of the Cerceris nests!

A little later, when I next checked, the burrow was open again. A prey-laden wasp approached but instantly backed off, dropping her prey near the entrance. Almost immediately another wasp reached out from the burrow and dragged the beetle below!

The exiled wasp repeatedly tried to enter the nest, but was repulsed each time. In the last photo (bottom right), the antennae of the resident wasp are visible. Clearly a Cerceris, and clearly intent on barring the entrance. Cerceris antipodes are known to share burrows, but the relationship is not always entirely amicable … clearly!

No prizes for guessing why these little pests are called satellite flies! Incoming, prey-carrying wasps are routinely orbited by a hovering miltogrammine fly … or two. The moment the wasp enters her nest, the flies land on the rim of the burrow and will often disappear inside.

This photo was taken immediately after a satellite fly landed briefly on the rim of the burrow. I watched the wriggling little fly larva (arrow … and yes, it’s rightly named a maggot) hang there for a few seconds, before it dropped into the nest opening. Once inside the burrow it would seek out a paralysed beetle. Ultimately, if it successfully evades the attention of the home owners, it will consume the food stashed in a Cerceris chamber, kill the host young, and ultimately pupate within the safety of the underground nest.

It’s an effective strategy. Miltogramminae (SARCOPHAGIDAE) are “major mortality factors for many if not most aculeate (stinging) wasp species” (Marshall, 2012, p. 385).

The nest site from 2022 is a flat patch of sandy soil … so this year I’ve been closely watching the area. The first wasps appeared mid August, soon followed by the first confirmed nesting activity. Here a female peers at me from the entrance to her nest.

As this species was only previously known from one museum specimen, these images are probably the first ever taken of the living wasps. Or at least the first images that can be identified to species level. (‘feeling chuffed’)

Females stock their nests with paralysed flies, food for their larvae. A variety of flies are targeted, but crane flies do seem something of a favourite. This fly is alive, but paralysed … and also legless! Crane flies have exceedingly long legs, and perhaps they simply get in the way during transport and storage. The wasps never seem to bother amputating other prey this way.

The very day that I first spotted nesting activity, and the opportunists had already moved in. The silvery fly watching the wasp’s every move is Apotropina … a known kleptoparasite of a variety of sand-nesting wasps.

This particular female had her burrow opening under a leaf. But something was deterring her from entering this time. She deposited her legless and paralysed prey on the soil, then hovered about while peering under the leaf. At first I suspected a lurking predator … perhaps a wolf spider …

… but then she started hauling rocks. It seems her burrow entrance had collapsed. Did we accidentally tread on it? Perhaps a passing wallaby had done the damage.

After a few minutes she dragged her prey out of sight beneath a nearby leaf, and then resumed work at her burrow. She eventually succeeded – the following day we saw her coming and going from the original nest.

A brand new source of pollen

This flower is the very first of the Dianella to open … and within a day the bees have found it. This female is shaking the anthers to release the pollen grains from the small opening at the end of each anther. Most of the pollen on her legs was collected elsewhere – most likely the nearby Aotus judging by the colour.

Lipotriches (Austronomia) (HALICTIDAE)

A bee hotel

‘Bee hotels’ provide valuable accommodation for many species of native bees. Lodger bees such as leafcutter and resin bees (family Megachilidae) and many colletids (subfamily Hylaeinae) make use of pre-existing holes in trees or logs. This old branch from an Angophora is riddled with hundreds of holes, probably the past work of beetle larvae. Now it makes the perfect, natural bee hotel!

Is the hotel currently in use? I’m sure of it. Although I’ve yet to get a good look at bees coming and going, there is a constant parade of bobbing Gasteruption wasps. And the most common hosts for Gasteruption larvae? … bees nesting in above ground cavities, including hotel lodgers (Parslow et. al., 2020)!

At home below ground

Many native bees nest in the soil, a habit retained from their ancestors among the crabronid wasps (Houston, 2018. p. 47). Indeed, this Lipotriches has a nest mound and opening immediately alongside a Cerceris (CRABRONIDAE) mound … and apart from the slightly larger opening, it’s difficult to distinguish the burrows. Until someone pokes their head out, that is.

Lipotriches australica (HALICTIDAE)

Leafcutter bee

Much excitement this day, as I have rarely seen bees of this family. The rather large head and thick mandibles, along with the pollen-carrying hairs beneath the abdomen, help distinguish Megachile from similarly coloured bees. This is a female … and the very next day I spotted a male! Another first for our home list.

Megachile (MEGACHILIDAE)

Showing off his specialised foreleg

Males of many bee species have modified front ‘feet’. Various authors have suggested a role for these tarsal expansions in the sex life of Megachile – ranging from blindfolds to help subdue their partners, to a source of chemical communication when used to hold or stroke her antennae (see Houston, 2018, p. 33). Fascinating!

Megachile (MEGACHILIDAE)

Down from the canopy

The first Euhesma sighting of the season. These little bees favour Myrtaceae (Eucalytus, Melaleuca, Leptospermum) and until this week the only Myrtaceae flowers were high in the canopy. The new blooms of Leptospermum are drawing them down within easy reach of my camera lens.

Euhesma (COLLETIDAE)

Cuckoo wasps: an uninvited hotel guest

Metallic colours, a thick cuticle, and compact build – instantly recognisable as a cuckoo wasp. These small, greenish wasps are our most common type. And they’re currently very interested in the bee hotel. The hole-riddled log must be providing rooms for wasps as well as bees, as Primeuchroeus has no interest in bees. She is a kleptoparasite of crabronids, sphecids and cavity-nesting vespids, exclusively. My bet is that small Pison are filling some of the hotel rooms with paralysed spiders … potential food and housing for cuckoo wasp larvae.

Primeuchroeus (HYMENOPTERA: CHRYSIDIDAE)

A future project

These large sand wasps are on my to-do list of crabronid studies. This patrolling male was my first Bembix sighting for the season. I expect many more to appear, and soon. The pressure is on to complete my current projects and get serious about Project Crabronidae (part two).

Bembix (HYMENOPTERA: CRABRONIDAE)

Banded bee fly

Yet another first for the season … and yet another kind of bee fly!

Tribe Villini (BOMBYLIIDAE: Anthracinae)

Natural demise, now a study subject

When I spotted this small wasp caught in a spider’s web I couldn’t resist a photo. Nor could I resist stealing the spider’s already envenomated prey for further study. She is now specimen number 2309H, and will teach me more about ichneumonid anatomy and diversity. Soon(ish).

HYMENOPTERA: ICHNEUMONIDAE

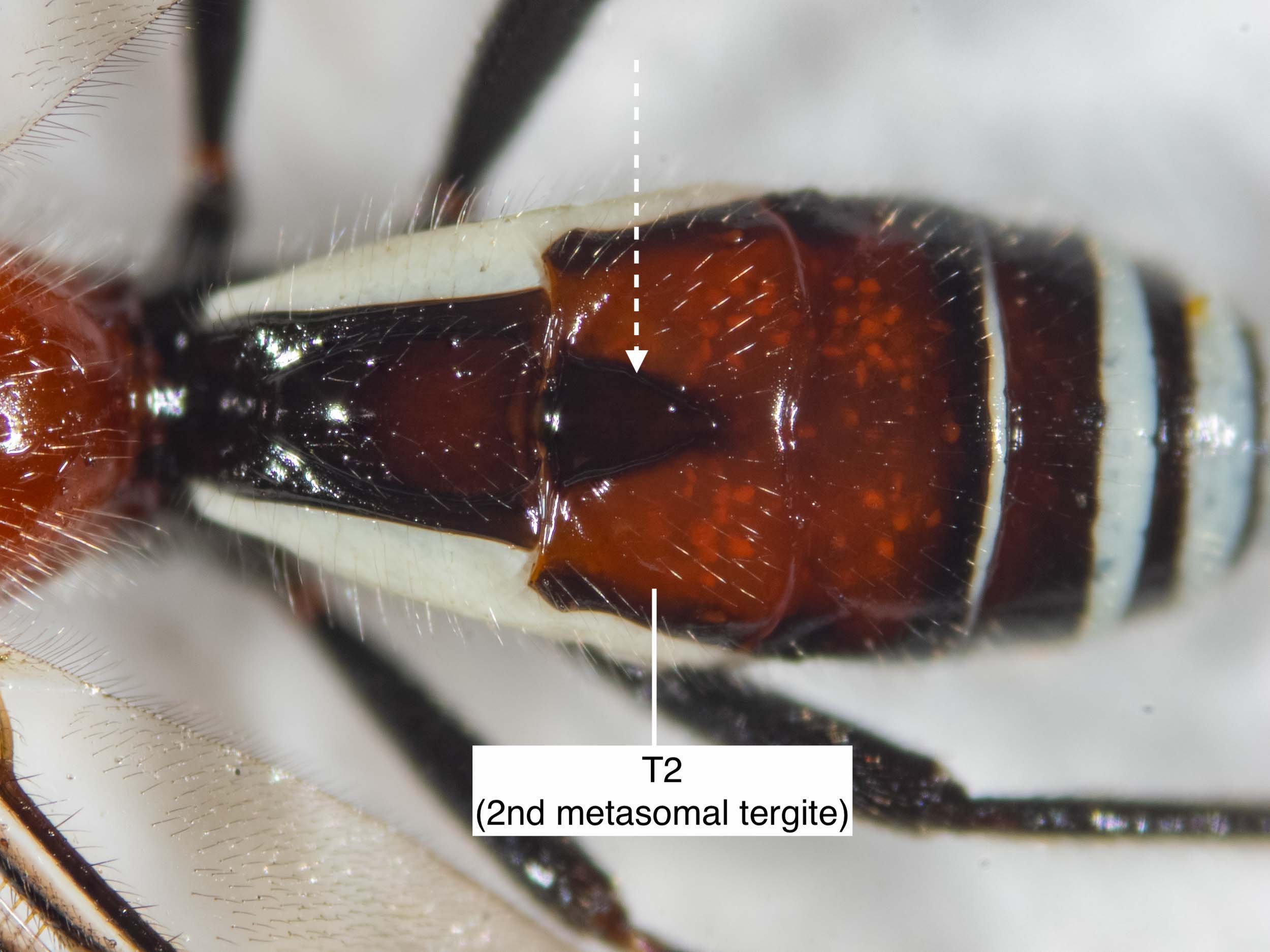

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

Pycnobraconoides

Callibracon

Vipiellus

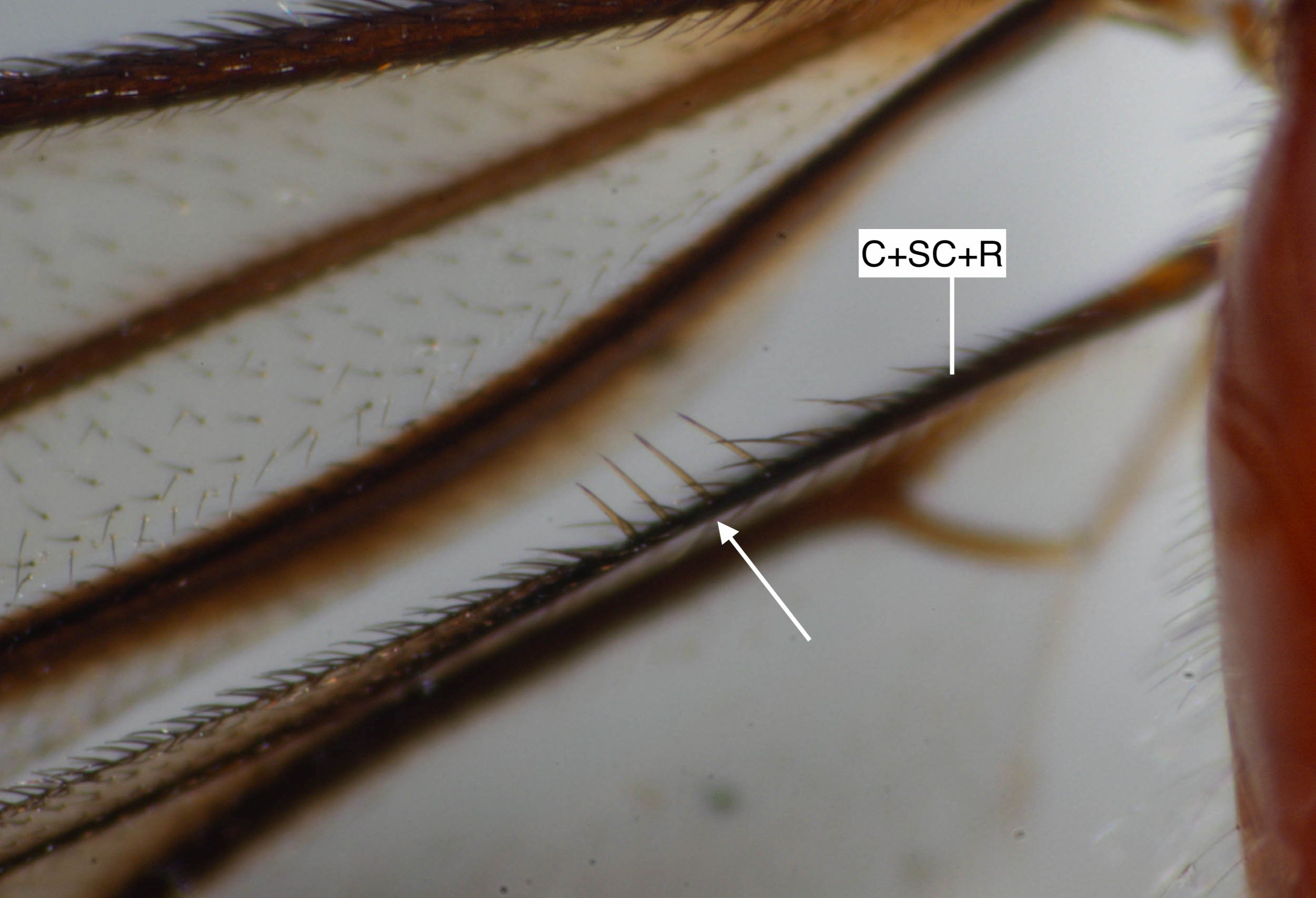

Forewing

Pycnobraconoides

Forewing

Callibracon

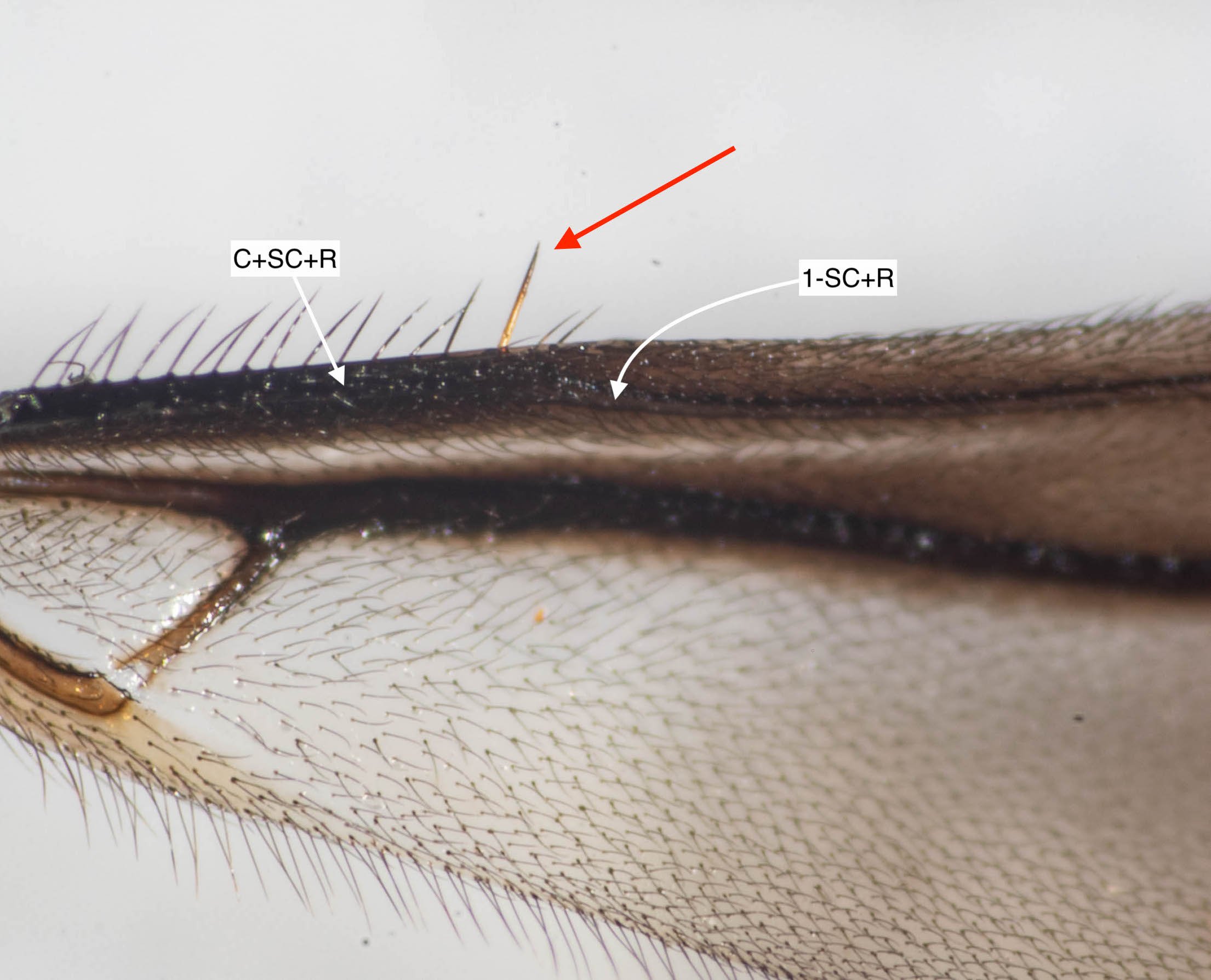

Leading edge of hindwing

Vipiellus

Hindwing

Pycnobraconoides

Hindwing

Callibracon

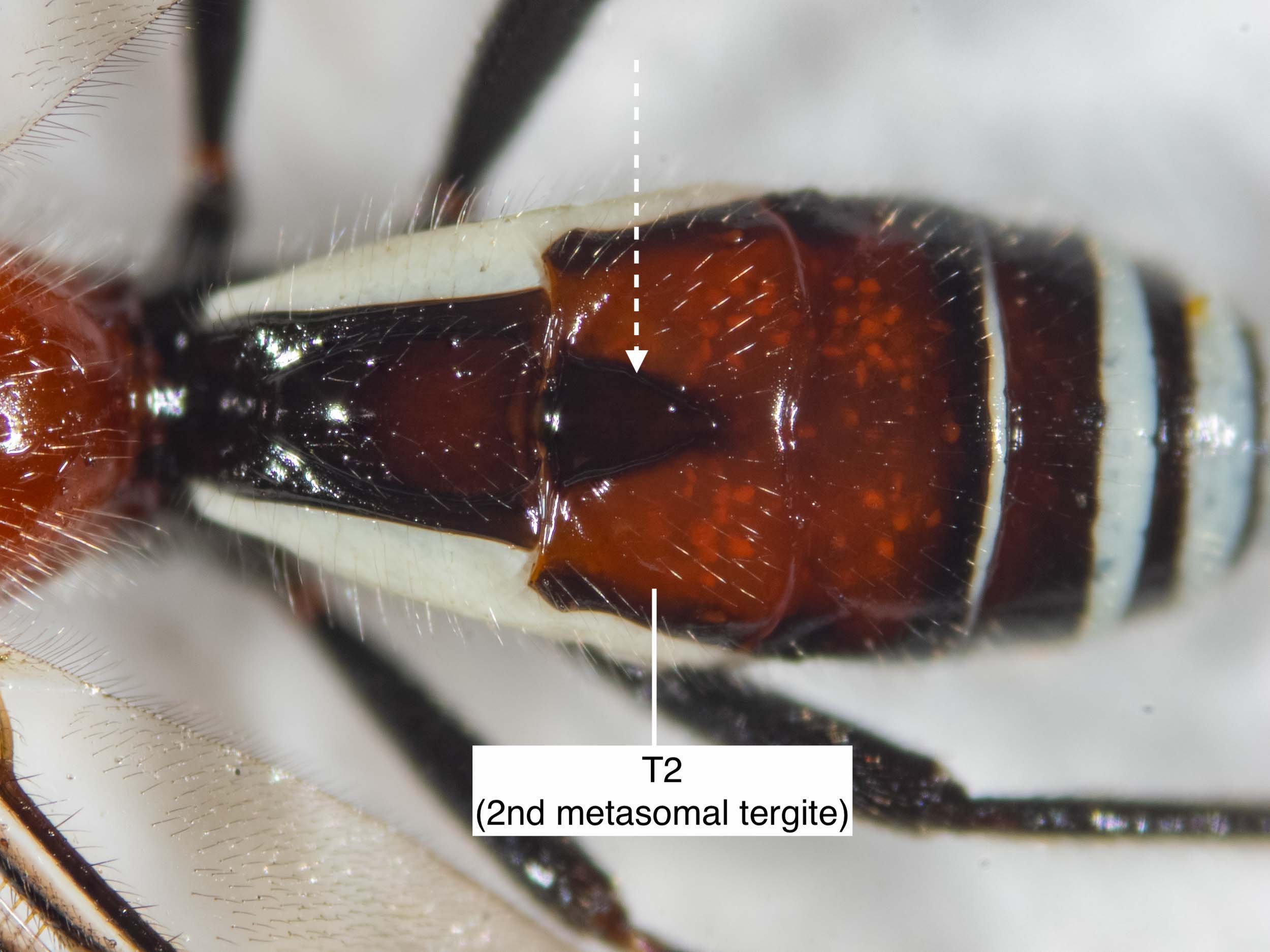

Museum records show only a single specimen of Rhopalum coriolum in collection – the original female collected a century ago near Sydney, and upon which the species was described (i.e. the holotype). We collected two females last year and another two this season. Once we’ve finished writing the paper, all will be deposited in Australian museums.

The differences between species are subtle, and require close-up photography. Rhopalum variitarse, a species known from Canberra, is very similar … but there are clear differences in fine structure and colour details.

This may be the first male ever collected. This one, and another we collected, will be sent to a museum once we have fully described and photographed them.